Conversation 52: What is going on between the change of habits and the composition of the board of internal characters that build the social self?

Greetings,

Today we want to talk about a topic that is important to many people. Many people want to lose weight, quite a few people want to start eating healthy or there may be someone who wants to start a vegetarian or vegan diet, quite a few people want to make a commitment to themselves and start doing sports, quite a few people promise themselves that they will join a certain workshop, or want to stop smoking or change habits, unfortunately for the most part things do not go well and if they do then only for a short period of time.

On the other hand, but interestingly, there are people who report that there are certain situations where they managed to change a habit such as quitting smoking and so on.

So an intriguing question remains here: what is behind the ability or inability to change habits?

Let's first define what a habit is: a habit is a regular practice or routine that is performed frequently, and in many cases, automatically. It is a pattern of behavior that develops through repetition and becomes ingrained, often to the point where it is carried out without conscious thought. Habits can be positive, such as exercising regularly or brushing your teeth, or negative, such as smoking or procrastination. They are created in a process where behavior is reinforced over and over again until it becomes a natural part of everyday life.

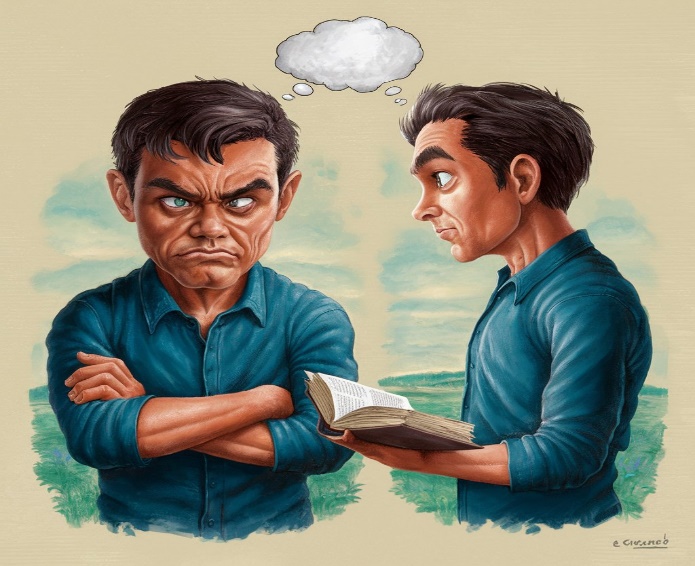

PICTURE 1

Illustration: "Yeremiah…want to change your habit? Here's an instruction book…"

Let's start with a general conversation about changing habits: changing habits in general involves understanding the psychological and behavioral processes that underlie the formation of habits and using specific techniques to change or replace unwanted habits with more desirable ones. Here are some detailed techniques for changing habits:

Identifying triggers and cues

• Observation: track when and where the habit occurs, and this is what triggers the behavior.

• Pattern recognition: Pay attention to the emotional, environmental and situational cues that lead to the habit.

Setting clear and specific goals

• Define goals: clearly define which habit you want to change or develop.

• SMART GOALS: Make sure the goals are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound.

Use the habit loop

• Hint: This is the trigger that initiates the habit.

• Routine: analyze the behavior itself.

• Reward: Understand what satisfaction or benefit the habit provides.

• Change: change the routine [habit behavior] while keeping the same cue and reward.

change the leg

• Replacement: Replace the unwanted habit with a positive habit that meets the same need.

• Gradual changes: gradually move from an old habit to a new habit to ease the transition.

behavioral techniques

• Positive reinforcement: reward yourself for doing the new habit.

• Negative reinforcement: remove an unpleasant stimulus when the desired habit is performed.

• Punishment: apply a negative consequence to engaging in an unwanted habit (use with caution).

Environmental changes

Making changes to your environment can significantly affect your habits by reducing triggers for negative behaviors and promoting positive behaviors.

• Removing triggers: These are elements in your environment that encourage unwanted habits and eliminate or reduce their presence. For example, if you tend to snack on unhealthy foods while watching TV, remove those snacks from your living area.

• Introduce new cues: introduce cues in your environment that encourage the new habit. For example, if you want to start working out regularly, keep your workout clothes and equipment in a visible and accessible place.

Attention and awareness

Being aware of your behaviors and triggers can help you gain control over your habits.

• Mindfulness practice: Engage in mindfulness practices such as meditation to be more aware of your thoughts and actions. This awareness can help you identify the triggers and urges associated with your habits.

• Reflection: regularly reflect on your behaviors and progress. Journaling about your experiences and feelings related to the habit change can provide insight and help you stay motivated.

Social support

Enlisting the help and support of others can provide motivation, accountability and encouragement.

• Accountability Partners: Share your goals with a friend, family member, or coworker who can hold you accountable and provide support.

• Joining groups: Participate in support groups or communities with similar goals. This can provide a sense of belonging and mutual encouragement. For example, joining a running club if you want to start running regularly.

Implementation intentions

Creating specific plans that describe how you will respond to certain situations can make it easier for you to stick to new habits.

• If-then plans: Formulate plans like "If situation X arises, then we will do Y." For example, "If we feel stressed, then we will go for a 5-minute walk instead of smoking."

• Concrete plans: Make your intentions as concrete and specific as possible to reduce ambiguity and increase the likelihood of execution.

Gradual adjustments

Making small and gradual changes instead of drastic changes can lead to more sustainable habit change.

• Small steps: Break the process of changing habits into manageable steps. For example, if you want to start waking up earlier, gradually set your alarm clock 10 minutes earlier each day until you reach your desired wake-up time.

• Consistency: Focus on maintaining consistency with small changes rather than making large changes that may be difficult to sustain.

Monitor progress

Tracking your progress can help you stay motivated and identify patterns in your behavior.

Visualization and mental repetition

Using mental imagery to imagine yourself doing the new habit can build confidence and reduce anxiety.

• Visualization: Visualize yourself regularly successfully engaging in the new habit. Imagine the steps involved and the positive results.

• Journaling: Keep a daily or weekly journal to record your progress, challenges and successes. This can help you stay focused and spot patterns.

• Apps and tools: Use habit tracking apps to record your activities and receive reminders and encouragement. Many apps also provide visual progress charts, which can be motivating.

Self-compassion and patience

Be kind to yourself and recognize that change takes time. This can help you stay motivated and avoid discouragement.

• Forgiveness: If you slip up or miss progress, forgive yourself and see it as a learning opportunity rather than a failure. Understand that obstacles are a natural part of the process.

• Perseverance: Stay committed to your goals and be patient with yourself. Recognize that lasting change takes time and effort.

• Mental Rehearsal: Practice the habit mentally, which can help you prepare for doing it in real life and build confidence in your ability to perform the habit.

professional help

Seeking help from professionals who specialize in behavior change can provide valuable guidance and support.

• Therapists and Coaches: Work with a therapist or coach who can provide personalized strategies and support for your specific needs.

• Behavioral therapy: Consider therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to address underlying issues and thought patterns that contribute to unwanted habits.

Use a bundle of lures

Combining activities you enjoy with a less appealing task can make it easier for you to adopt new habits.

• Combining activities: This is activities you enjoy and combine them with the new habit you want to form. For example, only allow yourself to watch your favorite TV show while you exercise.

• Improving motivation: this technique leverages your natural desires to increase motivation and make the new habit more attractive.

Examples of actual techniques:

1. Improving the diet:

◦ Environmental changes: Remove unhealthy snacks from the home and keep healthy options, such as fruits and vegetables, easily accessible.

◦ Implementation intentions: Plan specific responses to cravings, such as "If we crave sweets, then we can have a piece of fruit."

◦ Track progress: Use the app to record your daily food intake and track your progress towards healthier eating.

2. Increasing physical activity:

◦ Attention and awareness: Pay attention to how you feel before and after training to strengthen the positive effects.

◦ Gradual adjustments: Start with short, manageable workouts and gradually increase the duration and intensity.

◦ Visualization: Visualize yourself enjoying yourself regularly and successfully completing your workouts.

3. Reducing screen time:

◦ Environmental changes: Define specific areas of the home where devices are not allowed, such as the bedroom.

◦ Social Support: Join a group or build a challenge with your friends to reduce screen time together.

◦ Temptation Pack: Allow yourself to check social media only while walking on a treadmill or doing light exercise.

By consistently applying these techniques, you can effectively change your habits and achieve lasting improvements in your behavior and lifestyle.

Leveraged commitment instruments

• Prior commitment: a commitment that will obligate you to a course of action. For example, sign up and pay for a gym membership in advance.

• Social or financial risks: Put something at stake, like a bet with friends, where you lose money or have to do a chore if you don't meet your habit goals.

stacking habits

Stacking habits

• Link new habits to existing habits: attach the new habit to an already established habit. For example, if you want to floss daily, do so immediately after brushing your teeth.

• Building a routine: build a sequence of habits, and create a routine in which one action naturally follows another.leveraged commitment instruments

Use of technology

• Reminder apps: Use apps that remind you to do your new habit at specific times.

• Wearables: Use fitness trackers to monitor physical activities and provide reminders or nudges.

environmental restructuring

• Optimize your environment: Organize your physical environment to support your new habit. For example, keep healthy snacks visible and easily accessible.

• Minimize temptations: remove or reduce cues to unwanted habits. If you want to stop watching TV late at night, remove the remote control from your bedroom.

Adopt growth mindsets

• Embrace challenges: see failures as opportunities to learn and grow.

• Continuous learning: Continue to educate yourself about the benefits of the new habit.

Cognitive restructuring

• Reframe negative thoughts: Challenge and change negative beliefs about your ability to change. Replace the phrase "we can't do it" with "we are able to change".

• Positive self-talk: Use positive statements and affirmations to reinforce your commitment to the new habit.

Reward exchange

• Immediate rewards: Find small, immediate rewards for completing the habit, such as enjoying a piece of fruit after a workout.

• Long-term rewards: Focus on the long-term benefits of the new habit, such as improved health or greater productivity.

Stress management

• Relaxation techniques: Incorporate stress-reducing methods such as meditation, deep breathing, or yoga to help manage stress that can trigger unwanted habits.

• Sufficient rest: Make sure you get enough sleep, factors such as fatigue can weaken willpower and increase the likelihood of falling back into old habits.

Self-monitoring and feedback

• Check-in: Frequently assess your progress and make adjustments as needed.

• Feedback loops: Use feedback from your performance to improve and adjust your strategies.

Examples of actual techniques:

1. Creating a reading habit:

◦ Trigger: Place a book on the pillow in the morning to suggest nighttime reading.

◦ Routine: Set a goal to read for 10 minutes every night before bed.

◦ Reward: Allow yourself a few minutes of a favorite TV show or a snack afterward.

2. Breaking the procrastination habit:

◦ Identifying triggers: notice when you tend to procrastinate (for example, when you are faced with large tasks).

◦ Implementation intentions: Create specific plans such as "If we start to procrastinate, then we will work on the task for only 5 minutes."

◦ Positive reinforcement: reward yourself with a break or a small treat after completing part of the task.

3. Developing the meditation habit:

◦ Habit stacking: Meditate right after your morning coffee.

◦ Using technology: Set a daily reminder on your phone to meditate at a certain time.

◦ Reorganizing the environment: Create a quiet and comfortable space dedicated to meditation.

Advanced techniques:

Mental intention with overcoming obstacles: Combine visualizing the positive results of your new habit (mental intention) while overcoming obstacles. This method helps you stay motivated and prepared.

Cognitive behavioral strategies: engaging in CBT techniques to treat and change the thought patterns that contribute to unwanted habits.

Reflection and adaptation:

• Continuous improvement: regularly check what works and what doesn't. Adjust your strategies based on your reflections.

• Celebrate milestones: Recognize and celebrate small victories along the way to keep motivation high.

By combining a variety of these techniques and adapting them to your specific needs and circumstances, you can significantly improve your ability to change habits effectively. Remember, the key to successful habit change is consistency, patience and a willingness to adapt as you learn more about what works best for you.

Below we will give two examples of changing habits that include different components and their combination: from things written by one of us [Y.L.]

Example 1: Internet viewing habits

The Internet has become a central work tool for many and therefore in order to address the phenomenon the user must be taught moderate and controlled use of this means as opposed to total abstinence. This field is relatively new and established studies that demonstrate the advantages and disadvantages of different treatment methods are accumulating. However, a number of measures that have been tried in addictions can be used for other activities. Here are some suggestions:

A] Changing habits and routines

Here, check with the patient the times of Internet use and residence, along with the context and patterns of use, and change them.

For example, if the patient connects to the Internet during the night, his login should be changed to another time, or if the user connects to his e-mail every hour, this pattern should be changed to once or twice a day and at specified times, or if the patient connects for hours without breaks, he should be encouraged to stop at 10 20 minutes the activity as every hour for example. Such a change of activity patterns and durations in the direction of the activity recession can be learned, until the acquisition of new compatible and more adaptive habits of using the Internet. Using stopwatches, alarm clocks and other time markers (for example, the length of a record or a CD with songs) or a variety of apps in order to know when to stop or start the activity again often allows the implementation of new usage patterns.

B] Setting clear and implementable goals for Internet use

Realistic goals should be set for use, for example reaching 25 hours per week instead of 40-50 hours per week. It is advisable to gradually decrease to this quota while recording the decrease in the diary and using time markers. Such a moderate decrease will give the user a feeling that the goal can be reached, which will increase his sense of control.

C] Cessation of specific activities on the Internet

There are activities such as chats (conversation groups), entering sex sites and more that become a main part of the patient's life with addictive characteristics and even as a substitute for relationships with significant others, it is recommended to stop them.

In this type of rehab, you can use behavioral techniques such as providing aversive stimulation, the stop technique, and more, as well as cognitive therapy. Such treatment will also make it possible to deal with defeatist statements, negative scripts in connection with the success of the treatment, self-statements that preceded the problematic use of the Internet, and more.

D] You noticed the connection between the problematic use of the Internet and other mental or addictive problems

Sometimes there is a swing phenomenon in which the problematic activity on the Internet increases as a compensation for attempts to detox from addictions to food or gambling, for example. In such a case, these interrelationships must be considered when treating Internet use disorder. Sometimes the phenomenon is also aggravated as a compensation for the appearance of a transient depressive or anxious state. In such cases it is possible to consult about the need for psychotherapeutic treatment and/or anti-anxiety or anti-depressant drug treatment.

E] Use of self-suggestions in which the patient repeats the suggestions that help him moderate the activity. For example, "Meeting the goals I set will allow me more free time that I can devote to improving the relationship with my family members" or "The Internet is a tool that must be used in a controlled and intelligent manner" or "I can control my activities on the Internet, it's up to me!" and more. Some recommend writing such sentences and hanging them next to the computer.

F] Developing strategies to deal with mental situations in which there is an urge to connect to the Internet. For example, practicing deep breathing, practicing muscle relaxation and guided imagery. Developing other occupations such as walking, engaging in other types of sports, etc.

G] Joining a support group. Group members can also develop a support network through the telephone so that each group member can call and receive support from other group members in times of distress.

H] We note that sometimes family therapy can also be used. Such treatment can give an explanation to the family members about the addiction to the Internet, improve the means of family communication and mobilize the family members for help in the treatment, as this can be of great help especially in the treatment of children and adolescents.

We note that it is important for the patient to perceive stuttering in the treatment not as the failure of the treatment but as a temporary deviation from the course of progress that can be corrected. Finally, it is advisable to schedule long-term follow-up appointments in the treatment in order to ensure the preservation of the therapeutic achievements.

Example 2: The habit of pulling hair

Trichotillomania is a persistent psychiatric disorder characterized by repeated and uncontrollable hair pulling, mostly the hair of the scalp, eyelashes, and eyebrows, and less frequently the pubic hair, beard and mustache (in men) and even the hair on the arms and legs. The disorder results in localized baldness.

Due to the shame, most sufferers of the disorder hide their baldness and most of them do not seek treatment until many years after the onset of the disorder, and some even refer to them as "the silent sufferers" or "those who suffer in secret".

The treatment of the disorder includes counseling and support, identifying conflict situations with significant figures and trying to resolve them, drug treatment alongside behavioral treatments including desensitization, paradoxical intention, changing habits, token economy, increasing awareness, giving punishment, etc.

Sometimes also cognitive therapy aimed at changing cognitions that maintain magic circles that contribute to the recurrence of hair pulling can contribute to change.

Also, several cases of hypnosis treatment were described, sometimes in combination with behavioral treatments.

Below we will describe an example of a behavioral treatment system for hair pulling.

This behavioral therapy has two components:

1] Habit Reversal Training

2] Stimulus control .

Habit reversal training is based on the behavioral principle of preventing a response on the one hand and adopting and learning an alternative pattern on the other. This training includes four stages:

A) Creating awareness of the habit itself, in our case hair pulling. While there are some who pull hair following an urge or stress prior to pulling, many pull hair when their attention is focused on activities such as reading, watching TV, driving, talking on the phone, etc., they usually notice the activity only when the hair pulling has stopped and often tend to forget events of a rip off from the recent past.

In order to create awareness, the patient receives self-monitoring sheets to fill in between the therapeutic sessions held every week. The patients follow and write down when the hair pulling happened, how long it lasted, how many hairs were pulled out, how strong the urge was, where the episodes happened, what they were doing at the time, and what their emotional state was.

Even patients who think they are aware of the circumstances of the tear are often surprised by the emerging patterns. Registration continues throughout the treatment period.

B] About a week after the start of the registration, the second phase begins. This stage includes learning progressive muscle relaxation that can be performed by instructions given on a voice recorder (or mobile phone). The practice is done once a day and takes about 20 minutes. Its purpose is to allow the patient to focus on herself and reduce stress.

After about two weeks, most patients are able to relax their body muscles and control their breathing. At this stage they are given a tape of a short relaxation exercise in which they focus their relaxation skills for 60 seconds. Now this abbreviated relaxation will be done several times a day while learning the third step.

C] The third stage includes learning diaphragmatic breathing. This learning helps in achieving relaxation and focusing the patient on her body, so that she is much more aware of her feelings and actions in her body on the one hand, and on the other hand it reduces tension and irritation that may encourage the hair pulling activity.

D] The fourth stage includes the acquisition of muscular tension activity that is somewhat opposite and incompatible with the hair pulling activity. This activity is called a "competing reaction". At this stage, the patient is taught to contract, for example, the fist of the hand in which she pulls out her hair, bend the elbow of that hand to 90 degrees and press the forearm and palm to the sides of the body at about waist level for about a minute.

The patient practices this with the therapist and then at home about three times a day, each time doing this activity about 10 times.

Finally, steps B, C and D are grouped into a complete inversion training unit. The patients are requested that whenever they have an urge to pull out their hair, they will perform the following actions: a. Relaxing the body at the same time as breathing through the diaphragm in your mouth for about 60 seconds and immediately after that, contract the palm into a fist and squeeze the palm and the clenched palm to the sides of the body for about 60 seconds.

The actions must be performed with the appearance of the urge and before tearing. However, if the patient found herself in the middle of pulling out her hair or even at the end of it, even then the combined habit reversal exercise can be started immediately.

We note that it is possible to learn to do the inversion training in different situations discreetly without attracting much attention. Usually the stripping is done when the patient is with herself and at that time there is usually no embarrassment if others observe it. If the sick mother is driving, she is only asked to breathe with her diaphragm and clench her fist on the steering wheel.

It is necessary to explain the importance of persistence and patience in applying the method. Patients may not see immediate results and become discouraged. The benefit must also be seen in sequence and not in black-and-white vision, so there is a difference if tens or hundreds or even thousands of hairs are pulled out in a day.

Patients often have low self-esteem and a history of many failures to stop stripping in the past and have also faced criticism and ridicule in the past when they declared that "this time they will stop stripping" and failed to do so.

Stimulus Control:

The training method in reversing the habits is effective in stopping the hair-pulling habit, but does not necessarily provide an answer to all the triggers (the stimuli that start the hair-pulling). In the irritation control method, the patient is first helped to identify, then to prevent and finally to avoid or change habits and activities, environmental factors, routines and situations that are related to or trigger hair pulling.

The goal is to be awake and consciously control the triggers that lead to withdrawal and to create learned and new connections between the urge to withdraw and new non-destructive behaviors. The treatment includes changing the environment, creating a new and alternative stimulus environment and reorganizing life habits.

Along with these two techniques, other techniques can also be combined: the self-talking technique in which the patient repeats the talking points that help her resist the hair pulling activity or cope with it. These sayings include: "Pilling off does not help, it only makes the situation worse"; "I can control the hair pulling if I keep trying"; "Every hair on my head counts"; "I don't have to give myself permission to slip" etc.

You can also use self-aggrandizements that help you persist in the treatment: "You are approaching a dangerous situation, keep your hands down"; "Get ready to use the habit reversal exercise – you have the right to choose." Using white cotton gloves or acrylic nail tips can sometimes help. When there is difficulty in awareness of pulling, these measures serve as memory anchors that remind the patient to stop pulling her hair. Once the awareness increases you can stop using them.

As a general rule, emotional encouragement of the patient is an important aspect alongside these techniques and the great patience of the therapist. Some patients will master these techniques within weeks, while others within months. We note that it is also desirable to combine cognitive therapy alongside behavioral therapy. This kind of treatment will also make it possible to deal with defeatist thoughts, negative scripts in connection with the success of the treatment, self-talk that precedes hair pulling, and more.

Finally, long-term maintenance of treatment is important. It is important for the patient to perceive setbacks not as treatment failure but as a temporary deviation from the course of progress that can be corrected. Some also recommend living a balanced life while reducing psychological and physical stress.

Now we will stop and return with a few words about the model we are developing in which we claim that our social self consists of a collection of significant figures for us that we have internalized during our development starting from early infancy such as parental figures, teacher figures, and other influential figures that we have met during life as spouses, close friends, leaders social and political and so on.

By the way, among these characters we also include characters that are characters that we call virtual, such as a certain character from literature, from mythology, from history, and more

These characters make up the collection of internalized characters that build our "social self" which we call metaphorically: the board of internalized characters or the internalized jury.

It is interesting that among these internalized characters there are also representations of our selves in different periods of life and we are also talking about a certain more schematic representation of the subculture in which we grew up.

Figure: AI simulation of the Board of Internalized Characters

It is also important to note that sometimes an internalized figure is not necessarily an influential external realistic figure, but there may even be several representations of the same figure from different periods of our lives, so for example we may have several internalized figures of the mother that represent internalizations of the mother in different periods of life.

This sometimes happens when there is a significant change in the expression and effect of the realistic character, for example after defining events. So the mother, for example, will be internalized as a young and active mother and further represented as an elderly and needy mother.

It should be noted that we are usually not aware that our social self is represented by a collection of internalized characters and we say: "I acted, I did" while these internalized characters behind the screen of awareness reflect our opinions, our feelings and often our attitudes and behaviors our.

From here we can begin to realize that when we talk about changing habits or changing certain behaviors – such as quitting smoking, losing weight, etc., then we can actually begin to observe what is happening with these internalized characters, including the internalized characters of our selves (self images) from different periods of our lives contained within the same directory of characters. Hence, in order to bring about a change, it is also necessary to change something that supports the change within the composition of these characters who, by the way, are built in a certain kind of hierarchy – at the head of which there is often a character or characters who are more influential than the other internalized ones that we sometimes metaphorically call the inner leader.

It is important to understand about the inner leader that this is an internalized character who is more influential relative to other internalized characters, and even exercises a certain censorship regarding what will and will not enter the board of internalized characters.

We should note that during the psychotherapy we often hear patients testifying to themselves: "I’m a looser, I can't do anything, I have two left hands, nobody likes me."

Here we are of course talking about low self-esteem and we can also assume that there is such an internalized character with an influence on the board of directors that makes it difficult to reach any kind of achievements, and that while this is working, the person who is unaware of its actions perceives himself in such a way as to be unsuccessful and then with a high probability this person will not believe in his abilities to make a change.

From here things start to get a little more complex. We can assume that no one was born with low self-confidence, we believe that low self-confidence develops when someone external who is realistically significant to us influenced us in a negative and even offensive way and we internalized him and now that character influences us from the directory of internalized characters and defines the way we treat ourselves.

Many times these are figures who were or are very close to us, sometimes these are our parents, father or mother who made sure to repeat at the time how unsuccessful and hopeless we are, that we are not worthy, etc.

The same messages from the significant people for us at that time (usually at a young age) were often internalized through the dominant figure [the inner leader] among the board of internalized figures and this figure is the one that gives us the feeling of low self-worth. When it is active, and affects us, we will not feel that we have the strength to change the habits or behavior.

This is how it happens that according to this character that influences us, the inner figure of ourselves that perceives itself as unsuccessful and hopeless is shaped. It is clear that this perception makes it very difficult for us to change and many times even if some kind of thought crosses our mind "I would like to be someone" then immediately comes a thought: "But I can't… it just won't work… because I won't succeed and I'm not capable of anything , I have two left hands…" etc.

And against this, we will present another case in which the internalized leader self, the figure that influences us, is completely different. Here the internalized character broadcasts: "You are very strong, everything you want you will eventually achieve, you are sometimes able to change things that you didn't even imagine you could change, you have hidden powers that you have no idea that they exist."

In contrast to the previous case, a self-representation is created here that conveys self-confidence and high self-worth, "I'm basically capable of anything, I trust myself, I'm a strong person, if there's something that seems very difficult to me, I'll still overcome it".

Now let's say for example that a person wants to stop smoking, or start practicing sports. If we compare these two people described earlier between the one with the very low self-image [who has a critical leader figure that denies his abilities and as a result an inferior internalized self-representation figure] and the other person [who has a strengthening inner leader and a self-representation with a high self-image] it is almost certain that the former person will not even think of starting to practice sports or enter a smoking cessation process while the latter will have a much better chance.

Of course, even the same person with high self-confidence can have some internalized figures on the board of directors that interfere with the start of sports practice or the treatment of smoking addiction. For example, a character with the position that a smoker is "a man among men", something that links to other "masculine" activities such as climbing mountains, riding a heavy motorcycle, parachuting, etc. (and indeed this is widely used in cigarette advertisements).

Here we can definitely mention the importance of motivation, the very desire to change things. When we have no practical motivation there is no chance to change habits, but on the other hand we also understand that motivation does not always help and we try to understand why does it not help in some cases?

Here we want to bring a case that highlights how the image of the internalized self can hinder us from creating and accepting changes in habits and behaviors that have occurred in changing life circumstances. This is a case of a patient of one of us [IS]. The patient was an excellent skydiver. The parachute made him feel divine, he felt that he was a "king", that he was doing something that few are able to do. Unfortunately, he had a serious accident, with a serious injury to his body that required a long rehabilitation. After the accident, everything related to skydiving was forbidden to him. He developed in another field, a very interesting field, was very successful, was highly respected by his colleagues and managers. Everything was fine from the outside, but not for him. For him, he was a completely miserable person who hated himself.

The relationships in his family also broke down because he saw himself as unsuccessful and unworthy, he saw himself as completely unfit to comply with his previous self-image, which caused him to lose his self-esteem completely.

Here it is important to note that the figure of his father was internalized in him as a dominant figure. This father figure had very sharp positions and categories that focused mainly on the field of morality, positions that require the person to be very honest and responsible. The father had no patience for human weakness. Of course, all these qualities were not related to skydiving, but what connected the two was a position that the patient adopted in which "you do not deviate a millimeter from what you believe in", and thus skydiving became a sacred thing without which nothing is worth it. And so in his self-perception, once he couldn't skydive, he actually didn't meet the strict criteria that the internalized father figure set before him.

In fact, he extended the categorical moral part of his father's internalized figure to skydiving and treated the change in his ability to practice this hobby with the same degree of unforgiveness.

His self-perception therefore became a minefield for him, and created great difficulty in adapting to the new situation even though objectively there were quite a few advantages in the new situation. The treatment focused on the internalized characters, dealt with the flexibility of the positions of the internalized dominant character and the separation between the moral parts of it (the piercing honesty) and the practical instrumental parts (the ability to skydive).

Here we see an opportunity to say a few words about the importance of internalizing the figure of the therapist during the mental treatment. According to our perception, during treatment the character of the therapist becomes part of the patient's internalized character board. We also believe that the successful internalization of the figure of the therapist in the increasingly high position in the hierarchy of the internalized board is an important condition for good progress in therapy. In order to achieve this, the therapist's empathetic attitude towards the patient is of course important, an aspiration to deeply understand the "I believe" of the patient and of the internalized figures who manage him.

It is also important for the therapist to help rebuild the patient's self-confidence by emphasizing his achievements, the strengths he demonstrated in overcoming the difficult problems created following the accident and his progress in treatment. With the creation of trust in the therapist on the part of the patient, there is a chance that the internalized character of the therapist, which has more open and flexible attitudes and does not have a black-and-white vision, will allow the patient's rigid attitudes to be softened. The flexibility of positions may help in this specific case to accept himself in his new situation and significantly improve his quality of life.

It is important to emphasize that this is not the realistic figure of the therapist, but rather the figure that the therapist creates and shapes through the spectrum of his behavior and reactions for the purpose of the treatment in accordance with the goals of the treatment.

We note that it is also possible to use the internalized dominant figures in the patient, such as the example of the patient who was previously a skydiver – the internalized figure of the father, which is very dominant for the patient, can be used to support the patient's achievements in the new job, to praise him for the effort he made to deal with the results of the accident , and in order to help him separate the moral positions (pungent honesty) from the instrumental positions (ability to skydive).

Of course, it is important to focus the treatment not only on the dominant figures but also to allow access to additional internalized figures, some of whom may represent more open and adaptable positions, and within the framework of the treatment to raise them in the hierarchy within the internal board of directors.

There is another thing that is important to emphasize. In one of the previous blogs we talked about the sensitivity channels, our development that relates to the different sensitivity of each person to different triggers. According to our assumption, there are six such channels: norms, status, threat, attachment, routine and energy [see previous conversations].

As mentioned, different people have different sensitivities in each of these channels, whether with regard to their status or, for example, with regard to maintaining the norms or with regard to their subjective energy level: for example, for some of them, if their normal norm is not met, they enter a problematic emotional state, or for others, if their energy level decreases, they often enter a state of insufficiency.

Thus, if the threat channel in a certain person is particularly sensitive and he has a habit of smoking, then if this person receives a heart attack with a significant threat to his survival, then there is a good chance that he will show a high motivation to stop smoking. On the other hand, in a person with a less sensitive threat channel, it seems that his motivation to change can be less.

Another aspect we want to point out – is that of creating an internalized virtual character during the treatment (possibly in hypnosis but not necessarily) with features that allow the patient to deal better with the problem. This figure can be created during the treatment while also taking into account the patient's sensitivity channels in order to achieve optimal results.

In fact, with all the complexity of the subject, this is ultimately about working with the variety of internalized characters and inspiring changes that are required to achieve therapeutic efficiency.

In order to achieve this, we need to use the collection of the internalized characters that build the social self of the person, where there are also representations from different periods of the person's own self, while all these characters are in hierarchical relationships with each other.

We will add that the therapist's ability to intervene and change this hierarchy also has great significance for the external reference groups to which the person is exposed. For example, if someone suffers from an addiction and a habit of drinking alcohol and even his wife suffers from the same problem and not only does she not oppose his drinking but on the contrary, encourages him to drink, then his fight against addiction will be much more difficult. Of course, the subject of the habit of drinking or smoking also has a physiological dimension that we do not discuss in this article.

Below, as a kind of interesting exercise, we asked ChatGPT4 the following question: Assuming that the social self consists of the internalization of people who had a substantial influence on the individual, and that these internalized figures are arranged in a hierarchical order with the most influential internalized figure called the internal leader, and that habit depends on the interaction of these internalized figures, while each of them has its own attitudes, feelings and behavior – How will it be possible to use this background to change the persistent habits of the individual?

After receiving the answer, we removed contradictory parts of the answer and verified it while editing and adding critical changes. We note that the answer assumed very innocently [if one can attribute innocence to the software…] that the figure of the inner leader supports the change of the required habit…a bit innocent as mentioned on the part of the software, since in treatment we often have to deal with an inner leader in the board of internalized figures who opposes the change. But in cases where the internal leader supports the change, the answer gave interesting directions… and for those interested, here is the result:

In order to change resistant habits based on the perception of the social self consisting of internalized influential figures, the hierarchical arrangement and influence of these figures can be leveraged. Here's a detailed approach to using this background to facilitate habit change:

Identify the inner leader and the influential figures

• Self-reflection: Engage in deep self-reflection to identify the key figures who have a significant impact on you. These can be parents, teachers, mentors or close friends.

• Establishing a hierarchy: determine the hierarchy of these figures, with the inner leader being the most influential. Understand their attitudes, feelings and behaviors as they relate to you.

Understand the influence of internalized characters on current habits

• Behavior Analysis: Analyze how the attitudes, feelings and behaviors of each internalized character contribute to your current habits. For example, if an internalized character values discipline, this may affect your work habits.

• Emotional connection: Know the emotional connections and beliefs associated with each character in order to understand how these affect your resistance to changing certain habits.

Involve the inner leader

• Alignment of goals: Make sure your goals for changing the habit align with the values and attitudes of the inner leader. This can provide a strong motivational base.

• Internal dialogue: have an internal dialogue with the internal leader, imagine his support and guidance in the process of changing the habit.

Leverage support from other influential figures

• Supporting figures: This is what supportive internalized figures contribute to the change you want to make. Connect with their insider perspectives to strengthen your efforts.

• Dealing with Resistance: This is what nonsupportive characters may contribute to resistance. Try to understand their perspectives and find ways to address their concerns or reframe their influence.

Creating a coherent internal strategy

• Unified approach: Develop a strategy that creates harmony between the positions and support of the internal leader and other supporting figures. This unified approach can reduce internal conflicts and strengthen resolve.

• Positive reinforcement: Use the supportive voices of the internalized characters to provide positive reinforcement. Imagine their encouragement and approval as you move forward.

Internal imaging and repetition

• Visualize support: Regularly visualize your inner figures, especially the inner leader, and offer support and encouragement for the new habit.

• Mental rehearsal: mentally repeat situations in which the new habit is successfully performed with the inner characters cheering you on. It can build confidence and reduce anxiety.

Cognitive restructuring

• Reframe perspectives: Challenge and reframe negative beliefs or objections stemming from less supportive inner figures. Use rational and supportive voices to counter these negative beliefs.

Accountability for internalized characters

• Imaginal responsibility: Create a sense of responsibility towards your inner characters, especially towards the inner leader. Imagine reporting your progress to them and getting feedback from them.

• Symbolic rewards: Reward yourself in ways that you believe will be approved and appreciated by your inner figures.

Aligning the external environment with internal influences

• Consistency in Actions: Make sure your actions in the outer world reflect the values and attitudes of your most influential inner figures. This can create a sense of coherence and strengthen your determination.

• External support: seek external support from people who embody the positive qualities of your internalized characters. This external validation can strengthen your internal motivation.

• Positive self-talk: Engage in positive self-talk, relying on the attitudes and words you would expect from supportive internalized figures.

Treatment of in depth issues

• Therapeutic interventions: If the resistance is deep-rooted, consider seeking help from a therapist who can help you explore and treat the impact of the internalized figures more deeply, a therapist skilled in the treatment of internalized figures and their impact [RGFT].

• Personal Development: Engage in personal development activities that enhance the understanding and integration of these internalized influences.

Example – Breaking the smoking habit:

◦ Identifying internal influences: Recognize that an influential internal figure or perhaps even your internal leader (for example, a disciplined and health-conscious parent) disapproves of smoking.

◦ Inner dialogue: Have a dialogue with this inner leader, ask for his support and remind yourself of his values.

◦ Unified strategy: aligning the voices supporting and opposing smoking by reframing the perspective of internalized characters who might have supported or tolerated smoking.

◦ Visualization: Visualize the inner leader's approval and pride when you successfully quit smoking.

Developing a study routine:

◦ Identifying internal influences: determine that a mentor who values education is your internal leader.

◦ Internal dialogue: Imagine the mentor encouraging you to learn and expressing pride in your academic efforts.

◦ Unified strategy: Rely on supportive attitudes of other characters who value hard work and education.

◦ Visualization: Visualize confirmation from these figures as you set and achieve the learning goals.

Please be reminded that all of the above recommendations refer to supportive internalized characters only!

By understanding and harnessing the influence of internalized characters, especially the inner leader, it is possible to create a powerful internal coalition that supports and drives a change in habits. This approach combines psychological insight with practical strategies, and provides a comprehensive framework for overcoming resistance and achieving lasting behavioral change.

Here are five detailed examples of how to apply the concept of the social self and internalized characters to change resistant habits:

Example 1: Overcoming procrastination

Background

• Inner leader: a strict and disciplined teacher since school days who emphasized the importance of time management.

• Other influential figures: a parent who was relaxed about deadlines, and a friend who often procrastinated.

Stages

1. Identification of effects:

◦ Recognize that your inner leader values punctuality and discipline.

◦ Understand the parent's and friend's more relaxed approach to deadlines.

2. Coordinating goals:

◦ Define clear and time-bound goals for completing tasks, in accordance with the inner leader's values.

3. Internal dialogue:

◦ Imagine conversations with the inner leader that encourage timely completion of tasks.

◦ Address the more relaxed approaches and reframe them by emphasizing the benefits of completing tasks on time.

4. Unified strategy:

◦ Use the discipline of the inner leader to create a structured schedule.

◦ Neutralize the influence of the relaxed parent and friend by emphasizing the stress and consequences of procrastination.

5. Visualization and mental repetition:

◦ Visualize the inner leader expressing pride and approval as you complete tasks ahead of schedule.

◦ Mentally rehearse starting tasks immediately and enjoy the feeling of moving forward.

Example 2: Developing a regular exercise routine

background

• Inner leader: a fitness trainer who emphasized the importance of regular physical activity for health.

• Other influential figures: a sedentary brother who preferred leisure activities, and a colleague who enjoyed outdoor sports.

Stages

1. Identification of effects:

◦ Get to know the trainer's emphasis on the benefits of regular exercise.

◦ Understand the sibling's preference for inactivity and the partner's active lifestyle.

2. Coordinating goals:

◦ Set a specific training goal that aligns with the trainer's values, such as training three times a week.

3. Internal dialogue:

◦ Imagine the coach motivating you to stay active and emphasizing the health benefits.

◦ Address the sibling effect by focusing on the long-term health consequences of inactivity.

4. Unified strategy:

◦ Use the trainer's motivation to create a structured training plan.

◦ Take advantage of your colleague's enjoyment of sports to make exercise more enjoyable by trying different outdoor activities.

5. Visualization and mental repetition:

◦ Visualize the coach applauding your efforts and improvements.

◦ Mental repetitions of the routine, focusing on the positive feelings after the end of the training.

Example 3: Reducing screen time

Background

• Inner leader: A mentor who valued personal development and limited screen time.

• Other influential figures: a friend who spent hours on social networks, and a brother who preferred to read books.

Stages

1. Identification of effects:

◦ Get to know the mentor's emphasis on productive use of time and personal development.

◦ Understand the friend's heavy use of social media and the brother's preference for reading.

2. Coordinating goals:

◦ Set specific goals to reduce screen time and increase productive activities, such as reading.

3. Internal dialogue:

◦ Imagine the mentor's approval to reduce your screen time and focus more on personal development.

◦ Address the friend's influence by focusing on the benefits of less screen time and more productive activities.

4. Unified strategy:

◦ Use the Mentor values to set daily screen time limits.

◦ Take advantage of your sibling's preference for reading by swapping screen time for reading sessions.

5. Visualization and mental repetition:

◦ Visualize the mentor praising your reduced screen time and personal growth.

◦ Do mental rehearsals, engage in alternative activities such as reading or hobbies at times when you would normally be in front of screens.

Example 4: Eating healthier

Background

• An inner leader: a nutritionist who emphasized the importance of a balanced diet.

• Other influential figures: a parent who enjoyed cooking unhealthy meals, and a friend who followed a strict diet.

Stages

1. Identification of effects:

◦ Get to know a nutritionist's guidance on balanced eating.

◦ Understand the parent's preference for unhealthy foods and the friend's strict dietary habits.

2. Coordinating goals:

◦ Set clear nutritional goals that match the nutritionist's advice, such as eating more vegetables and reducing sugar intake.

3. Internal dialogue:

◦ Imagine the nutritionist's encouragement and advice as you plan meals.

◦ Address the parent influence by focusing on the long-term health benefits of a balanced diet.

4. Unified strategy:

◦ Use the advice of a nutritionist to create a healthy meal plan.

◦ Use friend discipline to maintain consistency in following the meal plan.

5. Visualization and mental repetition:

◦ Imagine the nutritionist's endorsement of your healthy eating choices.

◦ Mental rehearsals for choosing healthy foods and feeling energy and satiety.

Example 5: Quitting smoking

Background

• Inner leader: A close family member who successfully quit smoking after years of struggle and now advocates a smoke-free lifestyle.

• Other influential figures: a group of friends who smoke socially, and a spouse who does not like to smoke and encourages healthier habits.

Stages

1. Identification of effects:

◦ Family member: Learn about the family member's successful journey to quit smoking and their strong support for a smoke-free life.

◦ Friends: Understand the influence of smoking friends, who provide social cues and temptations.

◦ Partner: Pay attention to your partner's aversion to smoking and encouraging healthier habits.

2. Coordinating goals:

◦ Set yourself a goal to stop smoking completely, while adjusting to the family member's values and your partner's preferences for a smoke-free environment.

3. Internal dialogue:

◦ Family member: Visualize the family member's support and advice about quitting smoking, remembering their struggles and eventual success.

◦ Friends: Address the influence of smoking friends by focusing on the health consequences of smoking and the benefits of quitting.

◦ Spouse: Think about your partner's preferences and the effect smoking has on the relationship, emphasizing the importance of quitting smoking for mutual well-being.

4. Unified strategy:

◦ The family member's journey: Use the family member's experience as inspiration and guidance for your retirement journey. Ask for their advice on coping mechanisms and strategies to overcome cravings.

◦ Friend Influence: Reduce exposure to smoking triggers by spending less time with smoking friends or finding non-smoking social activities to engage in.

◦ Spouse Support: Lean on your partner for emotional support and responsibility. Involve them in the leaving process by sharing progress and celebrating milestones together.

5. Visualization and mental repetition:

◦ Visualization: Visualize the family member expressing pride and encouragement as you embark on your retirement journey. Imagine the health benefits and freedom from addiction that come with being smoke free.

◦ Mental rehearsal: mental scenarios in which you resist the urge to smoke, using coping strategies learned from a family member and drawing strength from the support of your partner.

By leveraging the influence of internalized figures such as the supportive family member and spouse, and minimizing the influence of smoking friends, it is possible to create a supportive environment that helps to quit smoking and adopt a healthier lifestyle.

Example 6: Improving sleeping habits

Background

• Inner leader: a doctor who emphasized the importance of good sleep hygiene.

• Other influential figures: a colleague who stayed up late at work, and a family member who preferred a strict sleep routine.

Stages

1. Identification of effects:

◦ Doctor: Know the doctor's emphasis on the health benefits of good sleep hygiene.

◦ Colleague: Understand the colleague's habit of working late at night.

◦ Family member: Pay attention to the rigid sleeping routine of the family member.

2. Coordinating goals:

◦ Set a specific goal to improve sleep, such as going to bed by 10pm every night. This is consistent with the doctor's advice on maintaining good sleep hygiene.

3. Internal dialogue:

◦ Doctor: Imagine your doctor's encouragement to maintain a consistent sleep schedule and the benefits of good sleep.

◦ Colleague: Address the impact of the colleague's late night habits by focusing on the doctor's advice and emphasizing the negative effects of insufficient sleep.

4. Unified strategy:

◦ Doctor's advice: Use the doctor's instructions to establish a consistent sleep routine, incorporating habits such as avoiding screens before bed, creating a relaxing bedtime ritual and ensuring a comfortable sleep environment.

◦ Family member's routine: Build on the family member's disciplined approach to bedtime, and adopt similar strategies to enforce a strict bedtime on yourself.

5. Visualization and mental repetition:

◦ Visualization: Regularly visualize your doctor's approval of your improved sleep habits and visualize the positive health effects such as increased energy and improved mood.

◦ Mental Rehearsal: Do a mental practice for your sleep routine, imagine each step like dimming the lights, reading a book or practicing relaxation exercises, and imagine yourself falling asleep easily and waking up refreshed.

Example 7: Reducing alcohol consumption

Background

• Inner Leader: A health-conscious colleague who promotes moderation in everything, including alcohol.

• Other influential characters: a group of friends who often drink together, and a brother who hardly drinks.

Stages

1. Identification of effects:

◦ Colleague: Learn about colleague's promotion of moderation and health.

◦ Group of friends: Understand the frequent drinking habits of the group of friends.

◦ Brother: Pay attention to the minimum alcohol consumption of the brother.

2. Coordinating goals:

◦ Set a goal to reduce alcohol consumption, aligning with the colleague's health-conscious approach.

3. Internal dialogue:

◦ Peer: Imagine the peer's support and advice on alcohol withdrawal.

◦ Friend group: Address the influence of the friend group by focusing on the siblings' healthier habits and the benefits of drinking less.

4. Unified strategy:

◦ Peer Advice: Use your peer's moderation advice to set clear limits on drinking.

◦ Sibling habits: base on the sibling's habits as a model for reducing consumption, such as choosing non-alcoholic beverages in social settings.

5. Visualization and mental repetition:

◦ Visualization: Imagine the colleague praising your efforts to drink less and feel healthier.

◦ Mental Rehearsal: Mentally rehearse social situations where you successfully limit your alcohol consumption, focusing on enjoying the company and activities without overindulging.

By implementing these steps, you can leverage the influence of internalized characters to support and strengthen your efforts to change resistant habits, making the process more effective and aligned with your inner values.

So much for now,

yours,

Dr. Igor Salganik and Prof. Joseph Levine

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Leave a comment