Conversation 56: The Directorate of Sigmund Freud's Internalized Characters

Greetings to our readers,

Freud is described in the introduction to the book "Dr. Freud Biography" by Paul Ferris "as a man with raging passions, who grew up in a culture that suppresses passions and who strived with all his heart to understand those passions that drive him…. An obsessed genius, sometimes evil, sometimes generous, here and there also mischievous . and Ferris is convinced that, like other pioneering researchers, Freud more than once hitched the cart before the horse….to draw the conclusions that seemed right to him at a given moment."

Is that so?

This time we will discuss in detail the figures that accompanied Freud's life and influenced his personality and the psychoanalytic thought he created and which were internalized in his directory of internalized figures. We will also try to maintain the hierarchy of these images in his inner world.

We will also add that we used various sources including Encyclopedia Britannica, the entry on Freud's life and thought in Wikipedia and Erich Fromm's writings on Freud, among other sources. We will also note that due to the fact that we will show different angles, there will be several repetitions of the same significant figures, each time in a different context.

Brief Biography

Sigmund (Shlomo) Freud was born on May 6, 1856 to Ukrainian Jewish parents, Amalia and Jacob Freud, in Freiburg, Moravia, a small town that was then part of the Austrian Empire. In his early childhood, Freud and his family moved to Leipzig and then to Vienna. Freud was a brilliant student, studied literature, biology and medicine, and graduated with a medical degree from the University of Vienna in 1881.

Sigmund Shlomo Freud [1856-1939]

Freud read widely as a young student, and his later theories were likely influenced by scientists and scholars of his time, as well as prominent continental philosophers, such as Nietzsche and Schopenhauer. Freud was also a devoted reader of Shakespeare, whose literary influence is evident in many of Freud's works.

The beginning of his life and training

Freud's father, Jacob, was a Jewish wool merchant who had been married once before marrying the boy's mother, Amelie Nathanson. The father, who was 40 years old when Freud was born, appears to be a relatively distant and authoritative figure, while his mother appears to be nurturing and more emotionally available.

Although Freud had two older half-siblings, his strongest, if most ambivalent, relationship seems to have been with his nephew, John, who was one year older than him, providing the model of close friend and hated rival that Freud often replicated in the later stages of his life

In 1859, the Freud family was forced for financial reasons to move to Leipzig and a year later to Vienna, where Freud remained until the annexation of Austria by the Nazis 78 years later.

Despite Freud's distaste for the Imperial City, among other things due to the frequent anti-Semitism of its citizens, psychoanalysis reflected in significant ways the cultural and political context from which it emerged. For example, Freud's sensitivity to the vulnerability of paternal authority within the psyche may well have been stimulated by the decline in power suffered by his father's generation, often liberal rationalists, in the Habsburg Empire.

Likewise, his interest in seducing girls was rooted in complex ways in the context of the Viennese attitude to female sexuality.

In 1873, Freud graduated from the Sprell Gymnasium and, apparently inspired by a public reading of a challenging essay on nature, turned to medicine as a career. At the University of Vienna he worked with one of the leading physiologists of his time, Ernst von Broca, an admirer and follower of the materialist, anti-vitalist, Hermann von Helmholtz.

In 1882 he entered the General Hospital in Vienna as a clinical assistant to train under the psychiatrist Theodor Meinert and the professor of the Department of Internal Medicine Hermann Nutnagel. In 1885, Freud was appointed a lecturer in neuropathology, after completing important research on the medulla of the brain.

During this time he also developed an interest in the pharmaceutical benefits of cocaine which he pursued for several years. Despite cocaine's beneficial results in eye surgery, which were credited to Freud's friend Carl Koller, the overall result of this practice was disastrous not only for Freud [it led to the addiction and death of another close friend, Ernst Fleischel von Marxow], but it also tarnished the Its medical reputation for a while. Today this episode is interpreted in terms of his lifelong willingness to try bold solutions to alleviate human suffering.

Freud's scientific training remains of cardinal importance in his work, or at least in his own perception. In writings such as "Entwurf einer Psychologie" (written 1895, published 1950; "Project for Scientific Psychology") he confirmed his intention to find a physiological and materialistic basis for his theories of the mind. Here a mechanistic neurophysiological model competed with a more organismic, phylogenetic model in ways that demonstrate Freud's complex debt to the science of his time.

At the end of 1885, Freud left Vienna to continue his neuropathology studies at the Salpêtrière Clinic in Paris, where he worked under the guidance of Jean-Martin Charcot. His 19 weeks in the French capital were a turning point in his career. Charcot's work with patients classified as "hysteria" presented to Freud the possibility that the origin of psychological disorders is mental and not in the brain.

Charcot's demonstration of the connection between hysterical symptoms, such as paralysis of a limb, as well as hypnotic suggestion hinted at the power of mental states and not of the nervous system as the cause of the condition. Although Freud was soon to abandon his belief in hypnosis, he returned to Vienna in February 1886 with the seed of his revolutionary psychological method.

A few months after his return, Freud married Martha Bernays, daughter of a respectable Jewish family whose ancestors included the chief rabbi of Hamburg and Heinrich Heine. She was to give birth to six children, one of whom, Anna Freud, would become a respected psychoanalyst in her own right.

Although the glowing picture of their marriage painted by Ernest Jones in his study The Life and Works of Sigmund Freud (1953-57) has been critically nuanced by later scholars, it is clear that Martha Bernays Freud was a very persistent presence during her husband's tumultuous career.

Shortly after his marriage, Freud began his closest friendship, with the Berlin doctor Wilhelm Fliess, whose role in the development of psychoanalysis sparked extensive discussion. During their 15-year intimacy, Fliess provided Freud with an invaluable interlocutor for his most daring ideas such as belief in human bisexuality, his idea of erotogenic zones in the body, and perhaps even the attribution of sexuality to infants.

A somewhat less controversial influence resulted from the partnership that Freud began with the physician Josef Breuer after his return from Paris. Freud turned to a clinic in neuropsychology, and the office he established at 19 Berggasse was to remain his consulting room for almost half a century. Before their collaboration began, in the early 1880s, Breuer treated a patient named Bertha Pappenheim – or "Anna O'", as she was called in the literature – who suffered from a variety of hysterical symptoms.

Instead of using hypnotic suggestion, as Charcot had done, Breuer allowed her to sink into a state similar to autohypnosis, in which she would talk about the initial manifestations of her symptoms. To Breuer's surprise, the very act of articulating and speaking seemed to provide some relief from their grip (although later studies have questioned this).

The "talking drug" or "chimney sweeper," as Breuer and Anna O. called it, respectively, worked cathartically to produce a response, or discharge, of the emotional blockage trapped at the root of the pathological behavior.

( from: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sigmund-Freud):

Additionally, an extensive section from Wikipedia:

Little is known about Freud's youth, as he destroyed his personal notes at least twice (in 1885 and 1907). His later letters were jealously guarded by the Sigmund Freud Archives, and were initially released only to his official biographer, Ernest Jones, and a few members of the inner circle of psychoanalysis. However, over the years almost all of his writings have been removed from the archive.

Studies and practice in research and medicine

During his medical studies, he engaged in research in the physiology laboratory of Ernst Wilhelm von Brücke in the years 1876-1882, in the field of nervous system histology. In 1877 he published his first article, on the subject of eel sexuality. In 1879, he stopped his studies for one year, to fulfill his duty and enlist in the Austrian army, where he treated sick soldiers, and in his spare time he translated articles by John Stuart Mill.

In 1880 he returned to his studies, completing his obligations for the degree of Doctor of Medicine in 1881. He continued to engage in research in von Brücke's laboratory that year, until he was persuaded by him to leave and move into medical practice in order to earn more money for his living.

In 1882, Freud got engaged to Martha Bernays from Hamburg (1861-1951), the granddaughter of Rabbi Yitzhak Bernays. They got engaged two months after they first met, when she visited Freud's family home, as a friend of one of his sisters. Six weeks after the engagement, Freud began to specialize in medicine in the various departments of the city's general hospital, and for three years gradually advanced through the ranks to the rank of Privatdozent ('first specialist' – a senior doctor in the department).

At the same time, he worked at the Institute of Anatomy under the guidance of the internist Hermann Nothnagel and later the neuropathologist Theodor Meynert, where he conducted research in the field of the human medulla oblongata (one of the parts of the brainstem) and nerve diseases.

The interior of Sigmund Freud's house in Vienna (now a Freud’s museum). From Wikipedia.

In the years 1884-1887, Freud studied the medical uses of the drug cocaine, and wrote the article "On Coca" ("Über Coca"). He claimed that cocaine may help reduce pain, depression and exhaustion, and can reward people addicted to morphine. He prescribed various doses of cocaine to some of his patients (including his fiancee Marta when she felt pain), and even took cocaine himself from time to time, as a stimulant to improve his general feeling.

However, Freud felt disappointment and failure in this area, when during this period his Jewish-Austrian ophthalmologist colleague Carl Koller studied the effects of the drug on animals, and gained most of the fame for his discovery of the effectiveness of the drug during local anesthesia in delicate eye surgeries.

Freud later discovered that following doses prescribed to his friend Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow to reduce his pain and his addiction to morphine – his friend consumed large amounts of cocaine and eventually became addicted to it, which contributed to Freud's sense of guilt, and disappointment in engaging in research on the cocaine. However, it appears that throughout his life Freud continued to use cocaine himself from time to time.

In October 1885, Freud went to Paris, for training in the field of nervous diseases with the renowned neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital. He was engaged in neurological research in his laboratory on children's cerebral palsy and aphasia, but there he mainly became acquainted with Charcot's methods for treating female hysteria, including hypnosis.

He was impressed by Charcot's style and personality (later, in 1889, he named his son Jean-Martin, after Charcot), as well as by his theatrical performances before researchers and doctors, in which he demonstrated hypnotic suggestion on women who suffered from hysterical paralysis in a certain part of their body and thus cured them.

This training was extremely significant for Freud, and following it he decided to move from research to clinical work with neurotic patients. On his way back to Vienna, Freud passed through Berlin, where he engaged for several weeks in further research on children's diseases.

In 1886 Freud returned to Vienna, and opened a private clinic specializing in brain and nervous disorders, where he conducted hypnosis treatments and experiments with his patients.

In this year he also married Martha Bernays, after four years of engagement, most of which he was far from her and corresponded with her very frequently. In 1887 his eldest daughter Matilda was born.

In 1887, Freud occasionally lectured on male hysteria, and in one of his lectures he met Wilhelm Fliess, a researcher from Berlin, who supported his ideas and became his close friend in the following years. In 1891 he published his study "On Aphasia", which dealt with the effects of neurological damage to the brain, on the impairment of verbal abilities – the ability to pronounce words and the ability to name familiar objects.

He claimed that these speech defects may also have a psychological component, and at this time he began to look for these components in his research and in his work with his patients.

The beginning of psychoanalysis

Freud noticed that the conventional treatment methods used at the time, including hypnosis, to treat hysteria and neuroses were ineffective. During this period he also began to reflect on sexual conflicts as a source of women's neuroses. As a result, in 1893 he began to write a book together with his colleague Josef Breuer, entitled "Studies on Hysteria" (Studien über Hysterie), in which a new method of treatment was described which was carried out by talking to the patient. During the treatment, Freud asked his patients to talk about their difficulties while lying on a couch. He encouraged them to say whatever came to their mind – a method now called "free association". The book was published in 1895.

The first case in which treatment was carried out using this method, and which is described in the book, occurred as early as 1880 – Breuer's treatment of the patient Bertha Pappenheim, who was mentioned by the nickname "Anna O". Before writing the book, Freud returned to this case, and developed a theory according to which the conversation with the patients may create a catharsis, evoke memories and release strong emotions, and thus lead to relief of the physical symptoms, as happened with Anna O'.

Visit to Clark University, 1909. Seated left to right: Freud, Stanley Hall, Carl Gustav Jung; Standing left to right: Abraham Brill, Ernest Jones, Sandor Ferenczi. From Wikipedia.

During 1895, Freud continued to develop psychological ideas about subjects such as melancholia, paranoia, and phobias, and also began to interpret his dreams. In 1896 he published "The Etiology of Hysteria" (Zur Ätiologie der Hysterie), where the term "psychoanalysis" appeared for the first time. At the same time, Freud continued neurological studies for Nuthnagel, and published in 1897 his study "Cerebral Palsy in Children".

In 1896 his father died, and Freud sank during his self-analysis into grief and reflections on the past, on his relationship with his father, and on their connection to psychological theories. During this period he developed the controversial "seduction theory", according to which neuroses in adulthood stem from mental trauma following sexual abuse by a parent of his child. He abandoned the theory during 1897. He realized that not all of his patients' neuroses stem from a sexual trauma that really happened in childhood, as they described during hypnosis and their treatments, but that it was a figment of their imagination and a mere childhood wish of the patients towards their parents.

He later developed in this regard the ideas about the Oedipus complex. Freud's colleague, Breuer, opposed these ideas about sexuality in childhood and its connection to neuroses, so during this period they parted ways.

During the following years, Freud began to think about the sexual conflicts and hidden desires of man, as contents that everyone tries to repress into their unconscious. These contents may emerge and be expressed in different ways, mainly through the person's dreams. Therefore, Freud claimed that the interpretation of these dreams may contribute to the understanding of the unconscious conflicts, and thus actually constitute "the king's road to the unconscious", as he defined it.

In 1900, his important book "The Interpretation of Dreams" (Die Traumdeutung) was published, in which he wrote about these ideas, and described analyzes of dozens of patients' dreams. In 1901, his book "Psychopathology of Everyday Life" (Zur Psychopathologie des Alltagslebens) was published, in which he described for the first time what has since become known as "Freudian language slip" – a slip from the mouth or a slip from a pen which is also a glimpse into the unconscious of the person.

In 1902 Freud accepted a professorship at the University of Vienna. He used to gather his colleagues every week for discussions using his method, in what has since been called the "Wednesday Psychological Society". In 1905 he published two books: "Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality" (Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie), in which he explained his ideas about sexuality in childhood, and described concepts such as the Oedipus complex, penis jealousy and castration anxiety; as well as the book "The joke and its relation to the unconscious" (Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewußten), in which he proposed the idea that humor or sarcasm is one of the ways in which the ego allows unconscious threatening content to be expressed consciously and in an adapted and acceptable manner in society.

In 1906, Freud's long-term acquaintance with Carl Gustav Jung began, and they began to correspond about psychoanalytic ideas. His other supporters during this period were Sandor Ferenczi, Ernest Jones and Carl Abraham. At that time, Otto Rank was appointed the secretary of the "Wednesday Psychological Society", which was renamed in 1908 to the "Vienna Psychoanalytic Society". In 1908, the first international psychoanalytic conference took place in Salzburg.

In the same year, his book "The 'cultural' sexual morality and the modern nervousness" (Die 'kulturelle' Sexualmoral und die moderne Nervosität) was published. In 1909 he published "Little Hans – An Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-Year-Old Boy", in which he presented the famous case of Little Hans, the first case description of psychoanalytic treatment of children – Hans suffered from a specific phobia of horses, and Freud treated him using interpretations based on the Oedipus complex. according to which the rapist transferred the castration anxiety from his father to a fear of horses.

Members of the "Vienna Psychoanalytic Society" in a photograph from 1922. Seated from the left: Freud, Sandor Ferenczi and Hans Sachs; Standing from left: Otto Rank, Carl Abraham, Max Eitingon and Ernest Jones. From Wikipedia.

In 1909, Freud visited the United States and lectured at Clark University, accompanied by Jung and Ferenczi. He founded the first journal of psychoanalysis, and appointed Jung as its editor. During this period, the first fissures began in the support of his colleagues: Max Eitingon, from his supporters in Zurich, began to criticize his views, Alfred Adler resigned from the "Vienna Psychoanalytic Society", and later others joined the criticism. From 1911 the tension between Freud and Jung increased.

In 1912, Jung published "The Psychology of the Unconscious", in which he distanced himself from Freud's ideas, and as a result, he resigned from the position of editor of the psychoanalytic journal and from the presidency of the International Association for Psychoanalysis, and broke away from Freud.

Freud, for his part, had little patience for colleagues who deviated from his psychoanalytic method. In 1914 he harshly attacked Jung and Adler in his article "Chronicles of the Psychoanalytic Movement", which became known as "The Bomb", and deepened the rift between him and his colleagues.

Other important books and articles published by Freud during this period are "On the Treatment of Dream Interpretation in Psychoanalysis" (1911), "On Narcissism" (1914), as well as "Totem and Tabu" (1913), in which he described his approach to the origins of culture and religion, in response to Jung's essays on the subject. At the same time, in 1912 he founded a psychoanalytic journal called "Imago", and appointed Otto Rank as its editor, and continued to hold the International Psychoanalytic Congress every few years.

During the First World War, he was engaged, among other things, in writing a large book on metapsychology, but in the end he left only five chapters of it and destroyed seven. After the war, he treated soldiers who suffered traumas during it. In 1919 he published his development of the concept of the threat (Unheimlich).

In 1920 he published "Beyond the Pleasure Principle" (Jenseits des Lustprinzips), about the impulses of pleasure (Eros) and death (Thanatos). The horrors of the war led him to emphasize that alongside the eros, the violent and destructive impulse is also a part of the human soul.

In 1921 he published "The Psychology of the Crowd and the Analysis of the Self", which discussed crowd psychology on the basis of the transformations that occur in the mental structure of the individual (where, among other things, Arthur Schopenhauer's "The Parable of the Porcupines" was examined), thus making another step in the study of the structure of the psyche that he alluded to In "Beyond the Pleasure Principle". In 1923 he published the continuation of Beyond the Pleasure Principle, "The Ego and the Id" (Das Ich und das Es), in which he described the structural model. During this period, cancer was discovered in his mouth, and he began a series of operations on his mouth.

In 1926 he developed the psychoanalytic theory about anxiety, and published his book "Inhibition, Symptom and Anxiety". In 1930, the city of Frankfurt awarded Freud the Goethe Prize, in recognition of his contribution to psychology. That same year his mother died, at the age of 95. In 1933, following the rise of the Nazis to power, Freud's books were publicly burned.

The last years of his life

Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna, photo from 1920. From Wikipedia.

Dr. Anton Sverwald, the Nazi officer appointed to take over the properties of the Jews in Austria, was a student of Freud's friend and decided to read his writings. The impression that Freud's writings left on the officer caused him to abuse his position. He hid from the Nazi government the existence of Swiss bank accounts owned by The Freud family, and even helped 16 family members get visas to escape to England.

The family also received financial assistance from Freud's patient and friend, Marie Bonaparte. When he asked to leave Austria, the Gestapo demanded that he sign a statement that he would be treated fairly. A popular anecdote attributed to Freud the cynical addition "I highly recommend the Gestapo to anyone", but the original document, which was discovered in 1989, refutes that anecdote.

On June 4, 1938, Freud and his family were allowed to cross the border into France, then continued from Paris to London, where they lived in the Hampstead area. Freud compared his going into exile to the request of Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakhai of Vespasianus before the destruction of the Second Temple: "Give me Yavneh and her wisdom." "We are about to initiate the same move" declared Freud, "after all, we are used to persecution."

At 20 Maresfield Gardens Street, London, Freud's residential address, the "Freud Museum" has been operating since 1986.

In London, in 1938, his ambition to gain the recognition of the Royal Society as a leading scientist was partially fulfilled, although a bill, initiated by Oliver Locker-Lampson, to grant him and other deported Jews British citizenship, failed. Two secretaries of the Royal Society brought the Society's book to Freud for signing. About this he wrote to his friend the writer Arnold Zweig: "They left me a copy of the book, and if you were here I could show you the signatures, from that of Isaac Newton to that of Charles Darwin. Good company!".

Freud smoked cigars for most of his life. In 1923, at the age of 67, he suffered from mouth cancer. He underwent over 30 treatments for the disease, including the removal of his upper jaw, but continued to smoke about 20 cigars a day until his death.

On September 23, 1939 (on Yom Kippur), after he could not bear the incessant pain caused by the disease, he asked his personal doctor to end his suffering, and died from an overdose of morphine given by a doctor. Three days after his death, Freud's body was cremated at Golders Green Funeral Home in North London. His ashes were placed in Ernest George's columbarium in Freud's Corner. It rests on a plinth designed by his son, Ernst, in an ancient Greek bell crater decorated with Dionysian scenes that Freud received as a gift from Marie Bonaparte, and kept in his study in Vienna for many years. After his wife Martha died in 1951, her ashes were also placed in the urn.

So much for an extensive section taken from Wikipedia, about Sigmund Freud.

And now we will move to a much more subjective enterprise and try to paint a psychological portrait of Freud from the perspective of our theoretical elaboration: Reference Group Focused Therapy (RGFT).

These hypotheses will be based mainly on some of Freud's biographies (Ernest Jones "The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud", Paul Ferris "A Biography of Dr. Freud", Peter Gay "Freud: A Life for Our Time", D. Harlan Wilson "Freud: The Penultimate Biography", his autobiographical notes ("Autobiographical Research"), Freud's book "The Interpretation of Dreams", and Erich Fromm's book "The Mission of Sigmund Freud: An Analysis of His Personality and Influence".

We note that the person himself and interviews with him are the best source for drawing such a portrait, But in their absence it is possible to use various sources including those close to him, the writings of the person himself and others about him. It must be remembered that the result is only a hypothesis.

Here we will first present the model we are developing for the social self or "the board of internalized figures", and then we will refer to the figures that surrounded Freud and were internalized in his psyche in the board of internalized figures, and the internal hierarchy between them.

Internalized key figures [usually human], usually refer to the significant people in a person's life who played central roles in shaping the individual's beliefs, values, and self-concept. These figures may include family members, friends, mentors, teachers, or any other influential person who has left a lasting impression on the person's psyche. Sometimes, these will also include historical, literary and other figures that left a noticeable mark on the person and were internalized by him. The term "internalized" implies that the influence of these key figures has been absorbed and integrated into the individual's thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors.

This internalization occurs through a process of observing, interacting with, and learning from these important people. As a result, the individual may adopt certain values, perspectives, and approaches to life that mirror those of the influential figures.

These internalized figures can serve as guiding forces in decision-making, moral thinking and emotional regulation. Positive influences can contribute to a person's well-being, security and resilience, while negative influences can lead to internal conflicts or challenges in personal development. Recognizing and understanding the influence of internalized human key figures is essential to self-awareness and personal growth. It allows people to evaluate the values they hold, question assumptions, and make informed decisions about the kind of person they want to be.

In addition, the awareness of these internalized influences can contribute to building healthier relationships and fostering positive relationships with others.

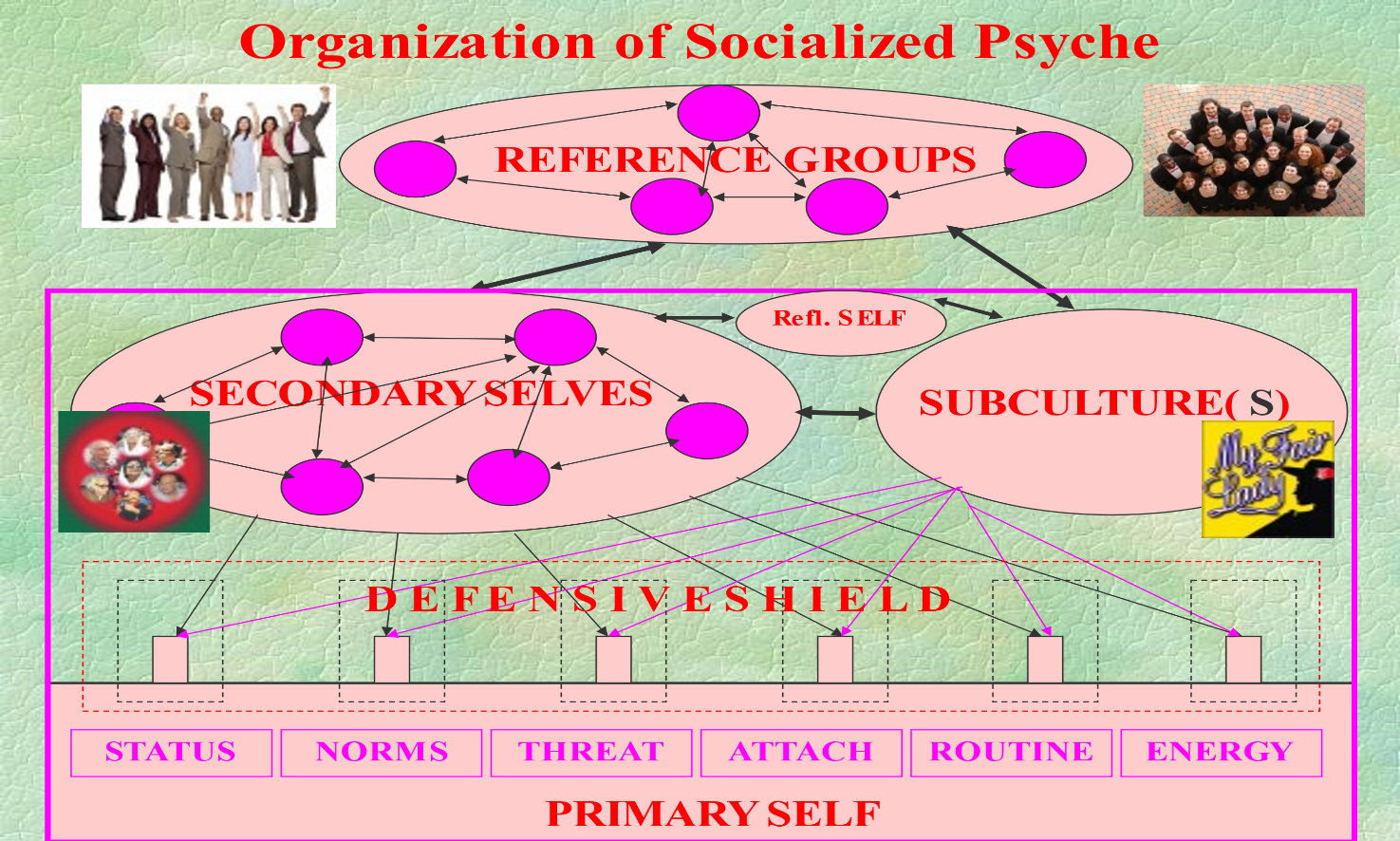

AI- assisted Illustration of the board of internalized characters

Below we will mention again the model we propose for the "Self": first, a distinction must be made between the "Primary Self", which is in fact the basic biological nucleus consisting of a number of innate structures and subject to development during life, and the "Social Self" [consisting of "Secondary Selves"], which is a structure that develops during the person's exposure to social influence, and consists of the internalization of figures significant to the person, originating from external groups or imaginary groups (related, for example, to a story, myth, film, etc.) that greatly influenced the person.

The "Secondary Selves" contained in the "Social Self" include: 1) the variety of representations of the "Me" that originate from attitudes and feelings towards the self and its representations in different periods of life, including an important representation of the "Reflective Self" [which observes the mental life of the person] 2] representations of characters’ internalizations often originate from significant characters that the person was exposed to during his life, but as mentioned may also be imaginary characters represented in books, movies, etc. that greatly influenced the person. 3] internalized representations of "subculture" [subculture refers to social influences in the environment [environment] in which the person lives and are not necessarily related to a particular person].

We call the "social self" metaphorically the "directorate of characters" or more precisely the "directorate or board of internalized characters", or the "council of characters". We note that in this internalized board of directors [this reference group], there is usually a hierarchy in which there are more influential and dominant figures that we metaphorically called "the Leader-Self" or "the internal leaders" and these set the tone and even censor and determine which contents, positions and behaviors cannot be included in the council of figures and it is also possible that none of the positions and feelings of figures on the board of directors will appeal to human awareness.

We note that the person as a whole is not usually aware of the influence of the board of the internalized characters and recognizes the influence as arising from his own desires and attitudes. We will also note that, as a general rule, the board is very dynamic and there are constant struggles and power relations between the internalized characters that make it up regarding the positions they will express, with the internal leader or internal leaders usually dictating the tone. The "board of internalized characters" includes the internalization of various external characters that influence the person, but we emphasize that usually the most important internalization is that of the one we called "the Leader-Self". Here it is about internalizing a character that has a great influence and shapes the person for good and/or bad, that has a major influence on the variety of internal characters that build the social self.

This inner leader has a decisive role and a profound influence on the internalization of external figures [or, in professional parlance, external objects]. He decides whether to reject the internalization or, if accepted, in what form it will be internalized. In other words, in a way, we assume that this influential figure is also a form of internal censorship.

It should be emphasized that we are not talking or raising concrete hypotheses about the presence of internalized characters in the inner world of the individual as a kind of "little people inside the brain", but rather in their representation in different brain areas whose nature and manner of representation in the brain still require further research. We will also note that although we call this figure a "leader", with the exception of a certain type, his characteristics are not the same as those of a dictatorial ruler in a certain country, but that this figure is dominant and influential among the internalized characters.

We note that for this model a treatment method known as "Reference Group Focused Therapy" or RGFT was developed, where the reference groups are usually a collection or board of internalized characters, and groups of people in the external reality who influence the individual in different ways.

In order to perform an analysis of Freud's personality in our terms we will have to refer to two main components included in our model. The model includes as mentioned:

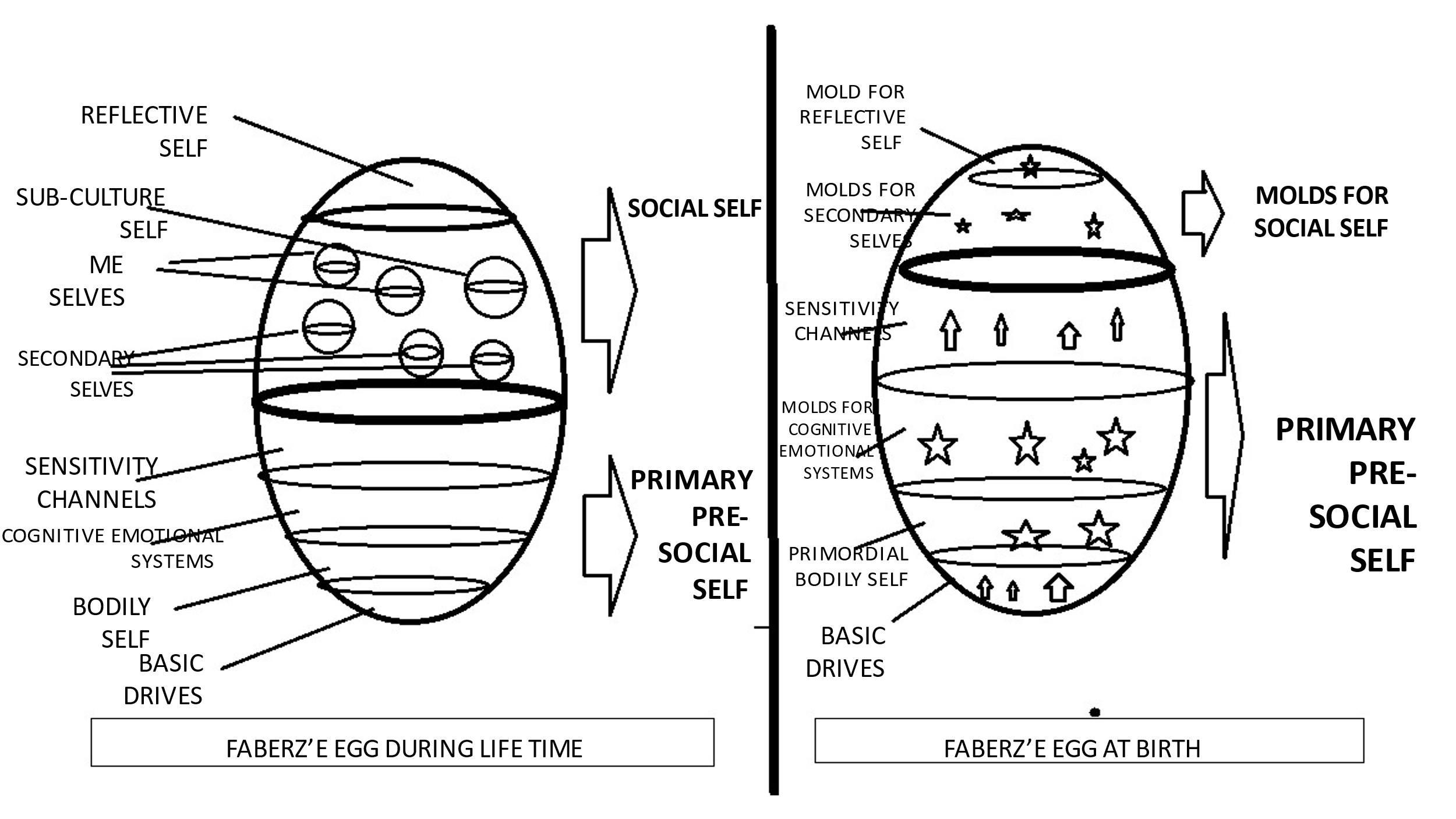

Primary Self (Biologically Predestined Core): Now, let's first address the Primary Self:

The Primary Self consists of innate biological structures and instincts that form the innate basis of personality and cognitive processes. This self has its own dynamics during a person's life and is subject to change with age, following diseases, traumas, drug consumption, addiction, etc. Both the instincts and the basic needs vary from one another in each and every individual – in addition, the instincts change according to different developmental periods and aging – (and hence their effect on behavior) and may change as mentioned through drugs, trauma, diseases and more.

Covered within the Primary Self is the potential for instrumental abilities which is innate but can also be promoted or on the contrary suppressed through the influence of the reference groups. The Primary Self also has cognitive abilities that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment during the first years of life. Apparently, they can be damaged or modified as a result of drug use, trauma, illness, aging. In addition, it includes the temperament and emotional intelligence that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment in the first years of life. Apparently, they can change as a result of drug use, trauma, disease, aging. And finally, it includes an energy charge that is mostly innate but can be suppressed through the influence of the reference groups as well as through situational factors.

Below is the illustration of the proposed model that we metaphorically called the "Faberge egg of the mind" at birth and later during life:

Two images depicting the theoretical model underlying RGFT

One of the most important theoretical developments in RGFT is Trigger Event Analysis (TEA).

TEA is an analysis of the triggers that contribute to considerable mental stress on a person during his life.

TEA divides all the triggers that lead to some kind of mental stress or strain on the person into six categories: status, norms, attachment, threat, routine, and energy (where each of these has a corresponding sensitivity channel, meaning there are also six sensitivity channels, see below). These triggers have explicit or implicit social characteristics, which means that they are related to reference groups [REFERENCE GROUPS: RG] whether internal, meaning internalized in the person's psyche, or external, meaning existing in external reality.

The given context of the results of mental harassment [which may contribute to mental deterioration] leads to the conclusion that these triggers should be treated as negative triggers – events that may accelerate mental deterioration in certain situations.

We can find the location of the sensitivity channels (as part of the Primary Self) in the figure above showing our theoretical model of the mind.

Below we will refer to the six individual sensitivity channels:

Individual Sensitivity Channels (ISC) reflect our individual reactivity in response to stressors (both external and internal). So far we have identified six sensitivity channels:

1. Sensitivity regarding one's status and position (Status Channel)

2. Sensitivity to changes in norms (Norms Channel)

3. Sensitivity regarding emotional attachment to others (Attachment Channel)

4. Sensitivity to threat (Threat Channel)

5. Sensitivity to routine changes (Routine Channel)

6. Sensitivity to a drop in energy level and the ability to act derived from it (Energy Channel)

Now let us turn to Sigmund Shlomo Freud and analyze Freud's channels of personal sensitivity. It seems that the channels that attract the most attention are in terms of their importance to him in the following order: the status, attachment, threat and energy channels.

We based such hypotheses mainly on quotations from some of Freud's biographies (Ernest Jones "The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud", Paul Ferris "Biography of Dr. Freud", Peter Gay "Freud: A Life for Our Time", D. Harlan Wilson "Freud: The Penultimate Biography", his autobiographical notes ("Autobiographical Research"), Freud's book "The Interpretation of Dreams", and especially from Erich Fromm's fascinating book "The Mission of Sigmund Freud: An Analysis of His Personality and Influence".

The Status Channel: "There may be other purely personal factors, such as, for example, Freud's desire to stand out…" (extended quote from Erich Fromm). "A man who was his mother's unshakable favorite retains for life the feeling of the conqueror, that confidence of success which often results in real success." (Quotation from Freud).

The Attachment Channel: "Of the thirty strange dreams of his that he [Freud] reports in "The Interpretation of Dreams" there are only two that deal with his mother… Both express a strong connection to her." (Fromm). Freud's dream about his mother: "I saw my beloved mother, with a strange peaceful and sleepy expression on her features, carried into the room by two (or three) people with a bird's beak, and laid down on the bed" (quote from Freud).

"He interpreted this dream as talking about the death of his mother, after he woke up from the dream in tears and screaming, all this testifies to his deep connection to his mother.” The deep connection to his mother is also reflected in the twilight of Freud's life. "He, who apart from his partners and colleagues… devoted free time to the man, including his wife, visited his mother every Sunday morning, and ordered her to visit him every Sunday for dinner, until he was old" (Fromm). "This need for attachment is reflected in the relationship with his wife and also with older men , his contemporaries and students, to whom he conveyed the … need for unconditional love, approval, and adoration and protection" (Fromm). "He resented his isolation, he suffered from it, but he was never willing, or even inclined, to even the smallest compromise that could have eased his isolation." ( Fromm).

"Here we could sense an internal conflict between Freud's longing for clinging [the need for attachment] and his longing for exclusivity [related to the need for status] as determining the words and attitudes of those who stand above the crowd. It is clear that the second longing won in most cases" (quote from Erich Fromm).

Sensitivity in the Threat Channel: "He was a very insecure person, easily feeling threatened, persecuted, betrayed, and therefore, as one might expect, with a great desire for certainty." (Quotation from Erich Fromm).. "My phobia, if you like, was poverty or rather, a phobia of hunger, which arose from my infantile gluttony and was called by the circumstance that my wife had no dowry (of which I am proud)" (Freud's letter to Fliess, December 21, 1899 ). In another letter to Fliess (May 7, 1900) he writes: "In general – except for one weak point, my fear of poverty, I have too much sense to complain…" Freud declared (1910): "My enemies will be ready to see me starve; They would tear my coat off my back." All these indicate a sensitivity in the threat channel in Freud.

Sensitivity in the Energy Channel: "There is no doubt that we must first think about intellectual virtue and vitality, far above average, which were part of Freud's strength" (Fromm). A quote indicating sensitivity in the energy channel.

By the way, when talking about Freud, one should also mention his multiple addictions: to cocaine, alcohol and cigars that affect cognition and emotion and the expressions of the primary self and even the secondary self. Addictions that end up responding to the sensitivity channel of the energy level by giving a temporary initial feeling of raising the energy level [especially cocaine] and calming the sense of threat [especially alcohol].

Thus, on April 21, 1884, in a letter to his fiancée, Martha Bernays, Freud wrote: "I read about cocaine, the effective ingredient of coca leaves, which some Indian tribes chew to make themselves resistant to deprivation and fatigue." Later he writes: "In my last depression I took coke again and a small dose lifted me to heights in a wonderful way [meaning increased energy]. I am now busy collecting the literature for a song of praise for this magical substance." The result of this search was an article by Freud on this substance the 'About Coke'.

It seems that Freud used cocaine to increase his productivity: "If a person works intensively under the influence of coca, after three to five hours there is a decrease in the feeling of well-being, and another dose of coca is needed to fight off fatigue… [meaning increased energy level]" ( quote from Freud),

Medical historian Howard Markel in his book "Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted and the Wonder Drug Cocaine" claims that this paper, in fact Freud's first major scientific publication, is a turning point for the young Freud. The way Sigmund combines his feelings, sensations and experiences in his scientific observations," writes Markel. "When comparing this research with his previous works, the reader cannot help but marvel at the vast transition he makes from documenting reproducible and quantitatively measurable and controllable laboratory observations to the study of thoughts and emotions.

Essentially, "Uber Coca" introduces a literary genre that would become a standard feature of Sigmund's work himself. From this point on, Freud often applies his own (and later his patients') experiences and thoughts to his writings as he works to create a universal theory of the psyche and human nature. It was a method that in its time turned out to be scientifically daring, sometimes somewhat imprudent, and in terms of the creation of psychoanalysis, incredibly productive."

Some skeptics attribute some of his dreams reported in the "Interpretation of Dreams" to the side effects of cocaine: "I see myself as a snowman, with a carrot nose, standing in a vast field of virgin snow, which all melts suddenly, like then, my nose falls and leaves me with a feeling of emptiness Deep…" "It's about a feeling of superiority at first that turns into fertility anxiety: the carrot is your penis…"

On the other hand, long term effects of cocaine can include depression, anxiety and panic attacks. Withdrawal symptoms may show cravings for cocaine, restlessness, hunger, difficulty sleeping and exhaustion. People often feel anxious and are very nervous during withdrawal. Other symptoms can include feeling depressed and a type of "emotional roughness," which makes cravings worse. It is important to note that some of these symptoms were reported by people who were close to Freud.

The misconceptions about the effects and side effects of cocaine led Freud to send samples of the substance to members of the medical profession, noting its potential application as a mental stimulant, treatment of asthma and eating disorders, an aphrodisiac, as a cure for morphine and alcohol addiction. He introduced him to Ernst von Fleischel-Marxow, a physiologist friend who took morphine to treat the chronic pain he suffered from a thumb injury during an autopsy. Instead of neutralizing his addiction, this added one more addiction to his addiction tank. Fleischel-Marksov was soon spending 6,000 marks a month on this new addictive habit of his, and died seven years later, at the age of 45 (Scott Oliver. "How Cocaine Influenced the Work of Sigmund Freud" https://www.vice.com/en/ article/payngv/how-cocaine-influenced-the-work-of-sigmund-freud).

His death left Freud with deep feelings of guilt. He reportedly stopped using cocaine in 1896, after his father's death. However, this habit was replaced by excessive drinking habits and increased cigar consumption (up to about 20 a day).

Now we would like to continue with Freud's description of the "social self".

First, we would like to suggest (and there are many indicators for this) that Freud from his early years grew up in a relative atmosphere of exclusivity, with the feeling that he was above others.

An unusually gifted person, Freud did very well in school from an early age. In high school, he was first in his class for 7 out of 8 years. This led to a variety of special privileges, including being rarely required to take any exams (Freud, 1952). An interesting and important enough detail for Freud to mention in his autobiographical notes: "At the gymnasium I was at the top of my class for seven years; I enjoyed special privileges there, and I could barely pass the class." It also led to privileges at home. According to his sister Anna, Freud always had his own room to study in, no matter how difficult the family's financial situation (Gay, 1998). In addition, while observing Freud's life path, it is difficult to avoid the impression that his main motivation in life was to be famous, to be admired by the crowd, to be one of the best.

Indirect hints of this can be found in Freud's writings about himself. "Not at that time, and not even at the beginning of my life, did I feel any particular inclination towards the career of a doctor… Under the strong influence of a friendship at school with a boy older than me who grew up to be a well-known politician, I developed a desire to study law like him and engage in social activity."

Then, interestingly, he changes direction under the influence of a man [Charles Darwin] who formulated an entirely new theory of the evolution of living things through an entirely different interpretation of the previously known facts: "At the same time, Darwin's theories, which were then of topical interest , attracted me greatly, as they held out hopes for extraordinary progress in our understanding of the world; and to hear Goethe's beautiful essay on nature read aloud in a popular lecture by Professor Ernst Bruecke right before I left school, that was what motivated me to become a medical student." (quote from Freud.

His first encounter with the academic world brought him together with two new insights about himself that led to the correction of his positions in relation to achieving his main goal – to become famous. The first was the anti-Semitic atmosphere within the university: "When, in 1873, I first joined the university, I experienced some considerable disappointments. Above all, I found that I was expected to feel inferior and foreign because I was a Jew. I absolutely refused to do the first of these things. I could never understand why I should To be ashamed of my origin or, as people began to say, of my "race" I resigned myself, without much regret, to not being accepted into the community. At a young age I became aware of the fate of being in the opposition and being under the boycott of the 'compact majority'.

Darwin's bitter experience appreciated by Freud, a scientist highly regarded by the contemporary scientific community, who initially rejected his theory, may also contribute to the construction of this attitude.

The second was the understanding of his own limitations, an insight that changed his search for the new "niche" he would pursue: "Furthermore, during my first years at the university, I had to discover that the peculiarities and limitations of my gifts prevented me from any success in many of the science departments to which my youthful eagerness had relegated me. This is how I learned the truth of Mephistopheles' warning: “Vergebens, dass ihr ringsum wissenschaftlich schweift, Ein jeder lernt nur, was er lernen kann”. Later we will discuss the approaches that allowed him to overcome these difficulties.

Following the line of thought, how the motivation to become not only the "top of the class" but the "top of humanity" guided Freud throughout his life. We must mention the episode in which Freud, despite his extensive experiments with cocaine, failed to discover the potential of cocaine for use as an anesthetic in ophthalmology, a fact first described by a fellow ophthalmologist, Carl Koller, who was the first to realize that the numbing effects of cocaine could be useful as a local anesthetic in eye surgery and became famous for it. This happened while Freud went on vacation with his fiancee Marta and it deeply hurt him: "It was my fiancee's fault that I wasn't already famous at this young age." Who knows, where Freud would have directed his further steps if he had succeeded in discovering this influence himself?

Another approach that eventually matched his high self-esteem and his motivation to be "on top" was his choice of workplaces and collaborators who were well known in the scientific community and of high social status. This attitude was explicitly expressed by Freud in giving advice to his son Martin. As Martin writes: "It was always his hope that one of his sons would become a lawyer. Thus he watched, and I think guided, my first faltering steps in law school with the greatest concern.

He agreed that my early studies were dull and boring, but assured me that one day I would find a teacher with an impressive personality, perhaps a genius, and that his lectures would deeply interest me and carry me away… Father always expressed himself very clearly, and when he advised me at such a critical time in my life, he added His usual clarity of expression has a natural tenderness and concern…" (M. Freud, 1983; p. 161).

This comment also demonstrates Freud's caring attitude towards his children, something that was mentioned by everyone.

Freud again says that medicine is not worthy, but something else interested him: "The various branches of medicine themselves, apart from psychiatry, did not attract me. I completely neglected my medical studies, and it was only in 1881 that I received my rather late degree as Doctor of Medicine."

He applies for a job in the laboratory of Ernst Wilhelm von Bruecke, one of the most prominent physiologists of his time. Freud writes: "At length, in Ernst Bruecke's physiological laboratory, I found complete rest and satisfaction – and also men, whom I could respect and see as my model: the great Bruecke and his assistants, Sigmund Exner and Ernst Fleischel von Marxow."

Working under Ernst Bruecke brought him another insight that translated into an attitude that accompanied the rest of his career: "In stark contrast to the scattered nature of my studies in my first years at university, I now developed a tendency to concentrate my work exclusively on a single subject or problem. This tendency has continued and has since led to my being accused of mono- versatility". (Freud).

He finds himself abandoning the basic research work (according to Freud – on Bruecke's advice): "The turning point came in 1882, when my teacher, to whom I attribute the highest possible esteem, corrected my father's benevolent oversight by strongly advising me , in light of my precarious financial situation, to abandon my theoretical career." Here two things can be distinguished: one is the permissive attitude of Freud's father to Freud's career ambitions (despite the family's problematic financial situation), and the other is Freud's own decision to leave a respected scientific laboratory in favor of greater financial gain (perhaps a reflection of his sensitive threat channel combined with the past experiences of living in relative poverty).

This anxiety – to be left without adequate means – dictates his next step: to turn to neurology, which was then a new and demanding specialty: "From a material point of view, the anatomy of the brain was certainly no better than physiology, and with financial considerations in mind, I began to research nervous diseases. There were few experts in that field of medicine at that time in Vienna…".

As a junior neurologist, Freud publishes several scientific articles and receives his first success that brings him a taste of fame: "I was the first person in Vienna to send a case for post-mortem with a diagnosis of polyneuritis acuta. The fame of my diagnoses and their confirmation after death brought me a stream of American doctors, who I spoke to the patients in my ward in a kind of broken English."

He decides to go to Paris, to Jean Martin Charcot who will later be called "the father of neurology" to make himself more knowledgeable in his new profession. By chance (Charcot needed someone to translate his lectures into German), he gets close to Jean Charcot and can communicate his thoughts to him freely. Charcot greatly impressed Freud, both in his personality and in his professional activity. Here Freud first encountered the clinical demonstrations of hysteria, including hysteria in men, which cannot be explained by contemporary theories.

Charcot's response that the phenomena he demonstrated cannot be explained using current scientific theories, was: "Ça n’empêche pas d'exister" [This does not rule out the existence of the phenomena that can’t be explained through existing theories] was often repeated from the mouth of Freud himself, and reflects the new approach he adopted, according to which it is not the theories or the perception of the events at a given time that govern the world, but the facts and the associated events.

What followed Freud's return to Vienna, could have been a severe blow for many, but not for Freud, and we will try to understand why: "I will now return to 1886, the year I settled in Vienna as a specialist in nervous diseases. I was obliged to report before the 'Gesellschaft der Aerzte' [Society of medicine] about what I had seen and learned with Jean Charcot. But when I reported it I was met with a bad reception, although people of authority, like the chairman (Bamberger), declared that what I said was amazing… Outside the hospital, I met with a case of a classical hysterical reaction in a man, and I demonstrated it to the 'Gesellschaft der Aerzte' [1886]. This time they applauded me, but they were no longer interested in me.

The impression that the higher authorities rejected my innovations remains unshaken; And with [my interest] in hysteria in men [and the treatment of] the man's hysterical paralysis [by means of] suggestion, I found myself forced into the opposition. Since a short time later I was removed from the brain anatomy laboratory and had nowhere to [update] my lectures, [since then] I retired from academic life and stopped participating in scholarly associations."

Freud's experience with electrotherapy and hypnosis, methods that were common at that time for the treatment of nervous diseases, strengthened his understanding (formed under the influence of Charcot) that he should rely only on the facts and not on theories or on the authorities: "My knowledge of electrotherapy was derived from the textbook of W. Erb [1882], who gave detailed instructions for the treatment of all the symptoms of nervous diseases. Fortunately, I could soon see that following these instructions was of no use at all, and that what I received as the epitome of accurate observations was merely a construction of fantasy.

The realization that the creation of the greatest name of the time in German neuropathology [Erb] has no more to do with reality than some Egyptian dream book, such as the one sold in cheap bookstores, was painful, but it helped me to get rid of another trace of naive belief in authority from which I was not yet free" (Freud).

Again, Freud was led to the conclusion that no matter what society (including scientific society) thinks of you, no matter how much they value your opponents and less you, you must stick to your own conclusions based on your own observations and logic.

We can see here how Freud gradually moves away from the so-called social truth, things that people believe to exist because other people or a group of people, called authorities, claim that they are true. This gives him the freedom to search for his own "truth", to walk in ways that no one else before has dared to walk.

In general, Sigmund Freud was influenced by a wide variety of significant people throughout his life. These figures, whether family members, mentors, peers or intellectual contemporaries, left a lasting imprint on his beliefs, values and self-concept. These influences built his social self, which we will try to explore. In order to understand the complex hierarchy of these internalized figures in Freud's psyche, they can be classified according to their influence and the roles they played in shaping his thoughts and attitudes.

It seems that Freud's social self is a complex structure, which develops from exposure to significant external influences. This can be metaphorically described as the "board of internalized characters", which includes, as we mentioned earlier, the following categories:

Leader-Self: the inner leader.

The most influential figure in Freud's internal hierarchy, the leader – self, acted as a central authority, shaped the internalization of other figures and determined which values and attitudes would be adopted or rejected. From various writings we will bring suggestions to the inner leader or inner leaders [there may be more than one] in Freud.

Family members:

Amalia Freud (mother)

Role: Maternal influence

Influence: Amalia's unconditional love and adoration undoubtedly contributed to Freud's high self-esteem. They strengthened the sensitivity channel of status in him, and allowed him to fight for his superior status even in difficult life situations where he was not properly understood or even rejected by the surrounding scientific community. His mother probably had some of the characteristics of the "Attachment Leader-Self" subtype (we previously classified 12 different subtypes of the Leader-Self, described in detail elsewhere).

Below we hypothesize some characteristics of this subtype of internalized leader-self: extensive use of feelings of guilt, criticism, social comparison. Others are seen as demeaning or ignoring by default, this can only be improved by intense attachment which in fact is never enough – the idea is to unconsciously try to improve the status by intensifying the attachment. The most involved emotions are: guilt, disappointment, feeling of inadequacy, pride. It seems that the sensitivity channels involved are status, attachment, norms. The most common attitudes are: I am the ultimate victim; The world is full of injustice towards me; I live through my children (for a woman); I live through my idea (for a man).

The behavior is often characterized by emotional fixation of others. The ways of influence are often: extensive use of creating feelings of guilt in others; extensive and unproductive criticism; Social comparison, mainly to emphasize the disadvantage of others. There is also some tendency towards narcissistic traits.

Some of these traits may have been internalized by Freud himself. This may partly explain his tendency to criticize any deviation of his partners from his original ideas, his intolerance of any criticism in his direction.

His mother's close and affectionate relationship with Freud probably influenced his theories of maternal attachment and the description of the dynamics of early childhood development in his writings. Her nurturing presence played a role in Freud's understanding of the importance of early relationships.

Role: paternal influence

Influence: His father was probably less dominant in the family. He also greatly admired Freud's intellectual skills, and despite the difficult financial situation provided the young Freud with everything he needed to begin the career of his choice. Although Sigmund Freud lost some respect for his father after his father told him a story about his humiliation by a Gentile without responding, he probably recognized how much his father's adaptive attitude enabled him later to face and overcome difficulties in his life.

But on the other hand, his father's eternal struggle to feed his family probably also emphasized the threat sensitivity channel in Freud and may explain his fears that he would not provide enough money for himself and later for his family.

Father Jacob's liberal thought and intellectual curiosity influenced Freud's interest in literature and philosophy. Freud's ambivalent feelings towards his father also contributed to his theories of the Oedipus complex and paternal authority.

Here is the place to mention that there are some signs of another internalized leader-self in Freud. In our classification we call this a rational leader-self. We do not have enough information to assume that this leader self originated with Freud's father, but there are some indications that its cumulative origin was drawn from some of Freud's most influential mentors such as Jean Charcot, von Bruecke, Meynert, and Breuer.

In our understanding this subtype of the leader-self is based on a perception of monopolistic superiority of the acquired positivist knowledge and experience.

In this subtype of inner leader objects are seen as always being in some logical relationship with one another, each change being caused by something that can be traced, at least theoretically, and can potentially be explained by a logical cause. It is a person's self-perception as a kind of analytical tool. The most common positions are: "Cogito ergo sum"; Logically sophisticated knowledge and empirically gathered experience are essential; There is a position that the emotional experience is an inferior way of seeing things; There is the principle of searching for innovations – in favor of dogmas. The way of influencing others: emphasizing thinking based on formal logic – establishing formal logic as a supreme norm of behavior. In some cases: isolation from external influences, and less need for social communication.

This is of course a generalization, but at certain moments in Freud's life we can discern a few features that fit some of this description.

The clear conflicts between the two internal leader selves of his mother and father (and probably some of his mentors) can sometimes explain seemingly contradictory behavior exhibited by Freud, for example, a sudden break in friendship or, on the contrary, long-term cooperation; unexpected and somewhat puzzling changes in behavior…

Since parents are naturally internalized in early childhood, usually as inner leaders, and these later influence who and how later figures in the internalized character board will be internalized, it is likely that they have maintained their role in leading the internalized figures in Freud's internalized figure board over time.

Martha Bernays Freud, although best known as Freud's wife, was also one of his closest friends and confidants. Their relationship, which began as a passionate courtship and developed into a lifelong partnership, provided Freud with emotional stability and personal support. The prolonged sexual abstinence of Martha and Freud at both at the beginning of their acquaintance and at an advanced stage in their lives may perhaps explain Freud's preoccupation with the sexual issue in his theoretical expansions or on the contrary be derived from this in addition to the fact that they had many children and this was a way to avoid further pregnancies.

Anna Freud, born in 1895, was the youngest of Freud's six children and the only one who followed his professional path. She became a prominent psychoanalyst in her own right, focusing on psychoanalysis of children and defense mechanisms. Anna remained close to her father throughout his life, helping him in his last years in London.

Influence on Freud: Anna's professional achievements and the close relationship between them influenced Freud's later work, especially his studies of defense mechanisms and child psychology. Her contribution helped expand and refine psychoanalytic theory, and established the legacy of the Freud family in the field of psychology.

Sophie Freud, born in 1893, was one of Freud's daughters who led a more traditional life compared to her sister Anna. She married and had children, but tragically died during the 1920 global flu pandemic.

Effect on Freud: Sophie's death had a profound effect on Freud, leading to an in-depth exploration of grief in his work. This personal loss influenced his seminal article "Mourning and Melancholy", in which he examined the processes of grief and the pathology of unresolved grief.

Ernst Freud, born in 1892, was an architect who had less influence on Freud's psychoanalytic work. However, he maintained a close relationship with his father and later played a significant role in managing Freud's legacy and estate.

Influence on Freud: While Ernst's professional life differed from his father's, the support and stability he provided contributed to the general well-being of the Freud family, allowing Sigmund to focus on his work.

Jean-Martin Freud, named after Freud's spiritual mentor, Jean-Martin Charcot, was born in 1889. He became an army officer and then worked in business. Like Ernst, his influence on Freud's work was indirect.

Influence on Freud: Jean-Martin's name symbolizes Freud's respect and admiration for Charcot, reflecting the interweaving of his personal and professional life. Jean-Martin's career and stability also contributed to the family support system that allowed Freud to continue his psychoanalytic efforts.

Sigmund Freud's family played a crucial role in his life, providing emotional support, inspiration and stability. Each of the family members, through their relationships and personal stories, influenced Freud's understanding of human psychology and contributed to the development of psychoanalytic theory. We hypothesize that despite the influence of those in Freud's board of figures, it was his father and mother who probably played a role as internal leaders. In addition, it seems that the interwoven personal and professional dynamics in the Freud family emphasize the profound impact of intimate relationships on intellectual and scientific pursuits.

Mentors and colleagues internalized in the board of Freud's figures:

Jean-Martin Charcot

Position: mentor and teacher

Influence: One of the most important instrumental approaches that Freud introduced with Charcot's character was that not theory but observation and logical thinking should guide a scientist in his work.

Charcot's work on hysteria and hypnosis was crucial in shaping Freud's understanding of the mind-body connection and the role of unconscious processes in psychological disorders. Charcot's demonstrations and ideas on neurology provided Freud with basic knowledge and methods that influenced the development of psychoanalysis.

It is likely that Charcot's name was used as the name of Freud's first son given to him so that he could symbolically take his place as the leading inner leader figure alongside the biological parents…

There are other key internalized figures who were high in the hierarchy of Freud's internalized figures at various times in his life and played significant roles in Freud's intellectual and personal development. They seem to have formed a high part of Freud's inner hierarchy and apparently influenced to varying degrees the board of his internalized figures, while contributing to the dynamic interrelationships within Freud's inner world.

Yosef Breuer

Role: collaborator and mentor

Influence: Breuer's work with Anna O. and the concept of the "talking cure" had a profound effect on the development of Freud's psychoanalytic techniques. Their collaboration in "Studies on Hysteria" marked the beginning of Freud's investigation of the unconscious. Breuer may have inspired the idea of psychoanalysis in Freud.

Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, initially collaborated closely with Freud and was considered his apparent heir. Jung's interest in mythology, religion and the collective subconscious led to the development of analytical psychology, a separate branch of psychoanalysis.

Despite their initial collaboration, Jung and Freud eventually parted ways due to theoretical differences.

Influence on Freud: Jung's collaboration with Freud contributed greatly to the expansion of the field of psychoanalysis. The exchange between them enriched Freud's understanding of symbolism, dreams and the unconscious. However, their theoretical disagreements, especially regarding the nature of the unconscious and the role of sexuality, led to a significant intellectual rift.

Alfred Adler, an Austrian physician, was an early member of Freud's inner circle. Adler developed his own school of thought, known as individual psychology, which emphasized the importance of social factors and feelings of inferiority in personality development. Adler's focus on the individual's drive for power and superiority contrasted with Freud's emphasis on sexual motivations.

Influence on Freud: Adler's ideas challenged and expanded Freud's perspectives on human motivation and behavior. The theoretical disagreements between them led to Adler's departure from Freud's circle, but his influence continued in the development of alternative approaches within the psychoanalytic movement.

Wilhelm Steckel, an Austrian physician and one of Freud's first followers, made significant contributions to the understanding of neuroses and symbolism. Steckel's work on anxiety, phobias and dream interpretation complemented Freud's theories and enriched the psychoanalytic discourse.

Influence on Freud: Steckel's contribution to dream analysis and the study of anxiety provided important insights that complemented Freud's work. His emphasis on symbolism and interpretation of unconscious material strengthened and expanded Freud's theoretical framework.

Sándor Ferenczi, a Hungarian psychoanalyst, was a close collaborator and confidant of Freud. Ferenczi made significant contributions to the understanding of trauma, child analysis and the therapeutic relationship. His innovative techniques and his compassionate approach to patients influenced the development of psychoanalytic practice.

Influence on Freud: Ferenczi's work on trauma and the therapeutic relationship profoundly influenced Freud's later theories. His emphasis on empathy and the importance of the analyst's emotional involvement in the therapeutic process influenced Freud's understanding of transference and countertransference.

Otto Rank, an Austrian psychoanalyst, was one of Freud's closest collaborators and a pioneering figure in psychoanalytic theory. Rank's work on birth trauma, creativity and the role of the artist in society expanded the boundaries of psychoanalysis. His book "Birth Trauma" suggested that the birth experience itself is a significant source of anxiety.

Influence on Freud: Rank's ideas about birth trauma and creativity influenced Freud's later work on anxiety and the origins of neurosis. Their collaboration enriched Freud's understanding of the unconscious and the role of early experiences in personality development.

Ernest Jones, a Welsh neurologist and psychoanalyst, was a key figure in the spread of psychoanalysis in the English-speaking world. Jones founded the British Psychoanalytic Society and played a crucial role in establishing psychoanalysis as a legitimate field of research. He also authored a comprehensive biography of Freud.

Influence on Freud: Jones's efforts to promote and institutionalize psychoanalysis helped spread it around the world. His biography of Freud remains a seminal work, providing important insights into Freud's life and the development of his theories. Freud's advocacy and organizational skills helped secure Freud's legacy.

Conclusion

Sigmund Freud's colleagues played central roles in the development and dissemination of psychoanalytic thought. Each of the collaborators brought unique perspectives and insights that enriched Freud's theories and contributed to the development of psychoanalysis.

Through their joint efforts and the intellectual exchange of ideas between themselves and Freud, these colleagues helped shape the foundations of modern psychology, ensuring the lasting impact of Freud's work on the field.

Here are the psychiatrists, neurologists and other doctors who influenced Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis:

Ernst von Bruecke, an Austrian physician and physiologist, was one of Freud's professors at the University of Vienna. Bruecke was a follower of the mechanistic view of the human body, and believed that physiological processes could be explained by physical laws. He was part of the "Vienna School of Medicine", which emphasized rigorous scientific methodology.

Influence on Freud: Bruecke's emphasis on scientific rigor and physiological explanations of behavior influenced Freud's approach to research and his initial focus on the biological aspects of psychology. Although Freud later moved toward psychological explanations, Bruecke's insistence on empirical evidence and scientific methods remained a cornerstone of Freud's work.

Theodor Meynert, an Austrian neuropathologist and psychiatrist, was another of Freud's influential professors at the University of Vienna. Meynert's work focused on the anatomical and physiological basis of mental disorders, and he was a leading figure in neuroanatomy and psychiatry.

Influence on Freud: Meynert's theory of brain structure and function provided Freud with a deep understanding of neuroanatomy and the biological underpinnings of mental illness. This knowledge was essential early in Freud's career as a neurologist and later influenced the development of psychoanalytic theory, particularly in understanding the physiological aspects of mental processes.

Franz Brentano, a German philosopher and psychologist, had a significant intellectual influence on Freud. Brentano's lectures on psychology and philosophy at the University of Vienna introduced Freud to the concept of intentionality and the descriptive approach to mental phenomena.

Influence on Freud: Brentano's ideas about the intention of consciousness and the importance of descriptive psychology influenced Freud's understanding of the mind and its processes. Although Freud ultimately chose a different path, Brentano's emphasis on the descriptive study of mental phenomena provided a philosophical basis for Freud's investigation of the unconscious and the dynamics of mental life.

Hermann Nuthnagel, an Austrian internist and neurologist, was one of Freud's mentors during his medical studies. Nuthnagel was known for his clinical acuity and his work on the localization of brain functions.

Influence on Freud: Nuthnagel's clinical expertise and focus on the neurological basis of disease influenced Freud's early medical training. The skills and knowledge that Freud acquired under Nuthnagel's guidance helped in his later work as a neurologist and in the clinical observations that led to the development of psychoanalysis.

Karl Klaus

Karl Klaus, an Austrian zoologist, was another of Freud's professors at the University of Vienna. Klaus's work in zoology and evolutionary biology provided Freud with a broad scientific perspective on biological processes and human behavior.

Influence on Freud: Klaus's theory of the evolution and biological basis of behavior contributed to Freud's understanding of human instincts and drives. This biological perspective was incorporated into Freud's psychoanalytic theory, particularly in his concepts of the libido and the death drive.

Eugene Bleuler

Eugen Bleuler, a Swiss psychiatrist, is best known for coining the term "schizophrenia" and for his work on the understanding and classification of mental disorders. Bleuler's emphasis on the biological and genetic basis of mental illness had a significant impact on early 20th century psychiatry.

Influence on Freud: Bleuler's work in psychiatry influenced Freud's thinking on the classification of mental disorders and the biological foundations of psychopathology. Bleuler's focus on the interaction between psychological and biological factors influenced Freud's holistic approach to mental illness, although Freud leaned more toward psychological explanations.

Emil Krepelin

Emil Krepelin, a German psychiatrist, is often referred to as the founder of modern scientific psychiatry. Krepelin developed a classification system for mental disorders that laid the foundation for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

He believed that mental illnesses had distinct biological causes and could be classified based on their symptoms.

Influence on Freud: Krepelin's work on the classification of mental illnesses influenced Freud's understanding of psychopathology. Although Freud disputed Krepelin's distinctly biological approach, Krepelin's emphasis on careful observation and classification of symptoms influenced Freud's own clinical methods and the development of psychoanalytic theory.

Pierre Janet

Pierre Janet, a French psychologist and neurologist, was a contemporary of Freud who also studied hysteria and the subconscious. Jean's concept of "dissociation" and his work on the psychological roots of hysteria parallel many of Freud's ideas, although they differed in their theoretical approaches.

Influence on Freud: Janet's work on dissociation and hysteria influenced Freud's theories of the unconscious and defense mechanisms. While Freud focused on repressed desires and the dynamics of the id, ego, and superego, Janet's ideas on the compartmentalization of consciousness provided an alternative perspective that enriched the broader field of psychology.

Conclusion