Conversation 59: Borderline personality disorder in the light of the model of the directorate of internalized characters

Hello to our readers

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is a mental condition characterized by a common pattern of instability in mood, behavior, self-image, and functioning. These patterns often result in impulsive actions and unstable relationships. People with BPD may experience intense episodes of anger, depression, and anxiety that can last from a few hours to a few days.

Emotional instability: People with BPD often experience rapid and intense mood swings. Their emotions can be extreme and change rapidly in response to stress or perceived threats to their self-image.

Distorted self-image: People with BPD may have an unstable or distorted sense of self, leading to frequent changes in goals, values, and aspirations. They may feel worthless, empty or misunderstood.

Fear of abandonment: A significant characteristic of BPD is an intense fear of abandonment or rejection. This fear can lead to frantic efforts to avoid being alone or maintain relationships, even if it means tolerating unhealthy situations.

Unstable Relationships: Relationships with others can be intense and chaotic. People with BPD may adore someone one moment and devalue them the next, reflecting their difficulty maintaining stable relationships.

Impulsive behavior: BPD can lead to risky behaviors, such as drug use, reckless driving, overeating, or self-harm. These actions are often attempts to deal with emotional pain or stress.

Chronic feelings of emptiness: Many people with BPD report feeling empty or hollow inside, which leads to a constant search for something or someone to fill this perceived emptiness.

Inappropriate anger: Intense anger or difficulty controlling anger is common in borderline personality disorder. This can manifest in verbal outbursts, physical fights or deep resentment towards others.

Paranoid thoughts and dissociation: In times of extreme stress, people with BPD may experience transient, stress-related paranoid thoughts or dissociative symptoms (a sense of detachment from themselves or reality).

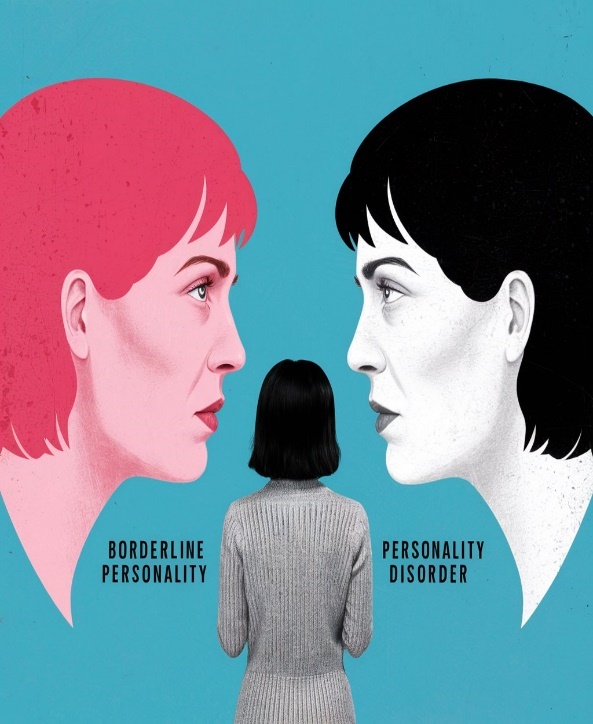

The perception of the representation of the self and the other as good or bad in borderline personality disorder: an illustration with the help of AI

The expressions of emotions in this disorder

In borderline personality disorder (BPD), a variety of influences, not necessarily significant to another person, deeply affect the sufferer of this personality disorder, leading to a variety of intense and rapidly changing emotional experiences. Here's a more detailed look at what's going on emotionally in people with BPD:

Emotional instability: One of the hallmarks of BPD is emotional instability, where people experience intense emotions that can change quickly. These emotional changes can occur in response to events that others may perceive as minor or manageable. For someone with BPD, these events can trigger strong and overwhelming emotions.

Rapid mood swings: People with BPD can experience extreme mood swings, going from happy to sad, angry, or anxious within a short period of time. These mood swings are often triggered by interpersonal interactions or perceived threats to their self-image or relationships.’

Increased emotional sensitivity: People with BPD are often described as having heightened sensitivity to emotional stimuli. They may respond more strongly to emotional triggers than others, and their emotions may take longer to return to baseline after being triggered.

Emotional Vulnerability: This heightened sensitivity means that emotions such as fear, anger or sadness can be triggered easily and strongly. This emotional vulnerability can lead to difficulties in managing daily stressors and challenges.

Chronic feelings of emptiness: Many people with BPD report chronic feelings of emptiness, which is a persistent feeling of emotional emptiness or numbness. This feeling of emptiness can be distressing and may lead people to seek intense emotional experiences to fill the void.

Emotional numbing: Sometimes, people with BPD may also experience emotional numbing, where they feel disconnected from their emotions or the world around them. This can be a defense mechanism to deal with overwhelming emotional pain.

Intense and unstable expressions of emotion: The observed expression of emotion is often intense and unstable in people with BPD. Observed emotions can change rapidly in response to internal or external stimuli, leading to a pattern of emotional reactivity that is difficult for others to predict or understand.

Emotional dysregulation: Emotional dysregulation in BPD is characterized by intense emotional reactions that may seem out of proportion to the situation. For example, minor conflicts can trigger intense anger, fear or despair.

Difficulty regulating emotions: People with BPD often struggle with regulating their emotions, meaning they find it challenging to manage and control their emotional responses. This difficulty in emotional regulation can lead to impulsive behaviors, such as self-harm or drug use, as a way to cope with emotional pain.

Self-representation as good or bad in BPD: an AI-assisted illustration

Maladaptive coping mechanisms: Due to their difficulty regulating emotions, people with BPD may resort to maladaptive coping strategies to manage their emotional distress. These strategies may provide temporary relief, but often lead to further emotional turmoil.

Fear of abandonment and related emotional reactions: Fear of abandonment is common in borderline personality disorder, leading to strong emotional reactions when people perceive they may be rejected or left alone. Such fear can set in motion a cycle of emotional dependency and instability in relationships.

Emotional intensity in relationships: Fear of abandonment can cause intense emotions in interpersonal relationships, including anxiety, anger, and despair. These feelings can lead to frantic efforts to avoid perceived abandonment, and sometimes even to go ahead and abandon others in order to avoid the other's abandonment.

Anger and aggression: People with BPD often experience intense anger, which can be difficult to control. This anger may be directed at others or turned inward in the form of self-harm or suicidal thoughts.

Inappropriate or intense anger: The anger associated with BPD can sometimes seem out of proportion to the situation. It can be triggered by perceived rejection, criticism, or frustration, leading to outbursts or aggressive behavior.

Emotional reactivity to stress: Stressful situations can exacerbate emotional instability in BPD, leading to heightened emotional reactivity. This reactivity can manifest itself in extreme anxiety, panic or depression, making it difficult for the individual to deal with even mild stressors.

Stress-related paranoia or dissociation: Under stress, some people with BPD may experience transient paranoia or dissociative symptoms, where they feel disconnected from reality or themselves. These experiences are often triggered by intense emotional responses to stress.

Conclusion

In borderline personality disorder, the expressions of emotions are characterized by a high level of instability, intensity and sensitivity. This lack of emotional regulation leads to significant challenges in managing daily life and relationships and a lot of stress. The intense emotions experienced by people with BPD are often felt to be overwhelming and uncontrollable, contributing to the distress and difficulties associated with the disorder. Understanding these emotional dynamics is essential to developing effective treatment strategies and providing support to people living with BPD.

We will now add here the definition of the disorder by the American classification method DSM-5:

In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the criteria for borderline personality disorder [BPD] are defined as a common pattern of instability in interpersonal relationships, unstable self-image, and marked impulsivity beginning in early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts , as evidenced by five or more of the following:

1] Fear of abandonment

2] Unstable self-image, including struggles with the sense of self and identity

3] Paranoia related to stress

4] Anger regulation problems, including frequent temper tantrums or physical fights

5] Consistent and constant feelings of sadness or worthlessness

6] Self-harm, suicidal thoughts or behavior

7] Frequent mood swings

8] Impulsive behaviors such as unsafe sex, reckless driving, overeating, drug use or excessive spending.

Factors and risk factors:

The exact cause of borderline personality disorder is not fully understood, but it is believed to be due to a combination of genetic, environmental and social factors. Risk factors include:

Genetics and family history

Those who have a first-degree relative, such as a parent or sibling who has borderline personality disorder, tend to be at a higher risk of developing the disorder. Family and twin studies support the potential role of a genetic component in the root of the disorder, with an estimated heritability of approximately 40%.

(Amad A, Ramoz N, Thomas P, Jardri R, Gorwood P. Genetics of borderline personality disorder: systematic review and proposal of an integrative model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014 Mar;40:6-19.

Environmental and social factors

The prevalence of traumatic life events such as childhood abuse and abandonment is high among those with borderline personality disorder, according to the NIMH. Factors such as these increase the risk of developing the disorder. It should also be noted that it is possible to develop borderline personality disorder without the presence of any of these factors. (National Institute of Mental Health. Borderline Personality Disorder. Available at:

www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/borderline-personality-disorder accessed October 2022).

It is also interesting to note that Paris found that by the age of 40, most BPD patients no longer met the criteria for the disorder. We will discuss this later.

(Paris J. Consequences of long-term outcomes research for management of patients with borderline personality disorder. Harv Rev 2002;10:315-23.)

Changes in brain function

Research suggests that people with BPD may have structural and functional changes in the brain, especially in areas associated with impulse control and emotional regulation. We will stop here and bring four suggestive reports about the brain changes observed in sufferers of this personality disorder:

First, the American National Institute of Mental Health – NIMH reports that people with borderline personality disorder may have structural differences in their brain compared to those without this disorder, and that this may drive functional changes in the brain related to impulse control and emotional regulation.

However, the agency adds that it is not yet known whether these differences correlate with the development of the disorder or whether the disorder itself creates changes in the brain.

(National Institute of Mental Health. borderline personality disorder. Available at: www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/borderline-personality-disorder Accessed October 2022).

Second, in a comprehensive review from 2007, Eric Lis and his colleagues reported on brain findings related to the disorder.

(Eric Lis, Brian Greenfield, Melissa Henry, Jean Marc Guilé, and Geoffrey Dougherty Neuroimaging and genetics of borderline personality disorder: a review. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007 May; 32(3): 162–173)

In general, these researchers believe that the study from a brain biological point of view provides interesting findings about brain changes in BPD patients. And so these authors write in the discussion of their paper using the horse and rider analogy: Imaging technology has shown that brain structures that have reduced volume in BPD patients may show hypermetabolism. It is possible that some of the lost volume in these structures (mainly, the amygdala) is related to the loss of inhibitory neurons, and this lack of inhibition can cause impulsive behavior and quite negative attributions. An apt analogy might be that of horse and rider: in BPD patients, emotional brain structures (the horse) run amok, while cognitive areas (the rider) are asleep, paralyzed, or unable to control this excess activity.

Third, researchers have generally used MRIs to study the brains of people with BPD. MRI brain scans use strong magnetic fields and radio waves to produce a detailed picture of the inside of the brain. The scans revealed that in many people with BPD, three parts of the brain were smaller than expected or had abnormal levels of activity. These parts were: 1] the amygdala – which plays an important role in regulating emotions, especially more "negative" emotions, such as fear, aggression and anxiety, 2] the hippocampus – which helps regulate behavior and self-control, and 3] the orbitofrontal cortex – which is involved in planning and decision-making. Dysfunction of these parts of the brain may contribute to the symptoms of BPD.

Fourth, researchers [Fertuck et al., 2023] have identified a brain region, the rostro-medial prefrontal cortex, which responds differently to social rejection in people with borderline personality disorder.

Normally, in a normal person the brain responds with rostro-medial prefrontal activity to rejection as if something is "wrong" in the environment. This brain activity may activate an attempt to restore and maintain close social ties in order to survive and thrive. This area of the brain is also activated when people try to understand the behavior of other people in light of their mental and emotional state.

However, people with BPD are characterized by interpersonal sensitivity to rejection and emotional instability – do not exhibit activity in the rostro-medial prefrontal cortex when rejected. Dysfunction in the rostromedial prefrontal cortex during rejection may therefore explain why individuals with BPD are more sensitive and distressed by rejection.

(Fertuck EA, Stanley B, Kleshchova O, Mann JJ, Hirsch J, Ochsner K, Pilkonis P, Erbe J, Grinband J. Rejection Distress Suppresses Medial Prefrontal Cortex in Borderline Personality Disorder. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2023 Jun;8(6):651-659.)

BPD can be challenging to treat, but with the right treatment, people can get better. Treatment usually includes:

Psychotherapy: Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is particularly effective in helping people with BPD manage their emotions, reduce self-destructive behaviors, and improve relationships.

Medications: While there are no medications specifically approved for BPD, antidepressants, antipsychotics, or mood stabilizers may be prescribed to manage symptoms.

Support groups: Group therapy or support groups can provide a sense of community and help people feel understood.

Later in the article, we will also discuss the possibility of treating this disorder with the method of treatment focused on the reference groups [RGFT].

A correct diagnosis is essential as with appropriate care and support, many people with BPD can achieve meaningful and fulfilling lives. However, it requires ongoing care, self-awareness, and a strong support network.

Understanding Borderline Personality Disorder: The Leading Theories

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a complex mental condition and researchers have developed several theories to explain the origins and mechanisms underlying BPD. These theories offer important insights into the disorder, and guide both clinical practice and ongoing research.

A biopsychosocial model

The biopsychosocial model is one of the most accepted frameworks for understanding borderline personality disorder. This model assumes that BPD results from complex interrelationships between biological, psychological and social factors.

Biological factors: Genetics and neurobiology play a crucial role in people's predisposition to borderline personality disorder. Studies have shown that BPD may be related to structural and functional disorders in brain areas responsible for emotional regulation, such as the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. In addition, genetic studies indicate that there is a hereditary component to borderline personality disorder, with certain genetic markers increasing the risk.

Psychological factors: These include personality traits and cognitive processes that may contribute to the development of BPD. For example, people with high levels of emotional sensitivity or a tendency to think negatively may be more vulnerable to developing the disorder.

Social factors: Early life experiences, such as childhood trauma, abuse, neglect, or dysfunctional family dynamics, are often involved in the development of BPD. Social factors, including the quality of interpersonal relationships and attachment styles, also play a significant role in shaping the disorder.

The biopsychosocial model emphasizes that BPD is not the result of a single factor but the result of the interaction of several factors, each of which contributes to the overall vulnerability and manifestation of the disorder.

Attachment theory

Originally developed by John Bowlby, attachment theory focuses on the importance of early relationships between infants and their primary caregivers. This theory has been extended to explain the development of BPD, suggesting that disruptions in early attachment can lead to emotional instability and the problematic relationships seen in the disorder.

John Bowlby – child psychiatrist and psychoanalyst

Insecure attachment styles: People with BPD often display different and insecure attachment styles. These styles are characterized by fear of abandonment, difficulty trusting others and intense and unstable relationships.

Early separation and loss: Attachment theory posits that early experiences of separation, loss, or inconsistent care can disrupt the development of secure attachment, leading to the intense fear of abandonment and dependency seen in BPD.

Internal Working Models: According to this theory, people develop internal models of self-concept and others based on their early attachment experiences. In BPD, these models are often negative, leading to a distorted self-image and difficulties in creating stable relationships.

Attachment theory emphasizes the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping the emotional and relational patterns that characterize BPD.

Dr. Marsha M. Linehan – University of Washington, USA

Emotional Vulnerability: According to Linehan, people with BPD have a biological predisposition to heightened emotional sensitivity, heightened emotional intensity, and a slow return to emotional baseline. This emotional vulnerability makes them more sensitive to the effects of environmental stressors.

An invalidating environment [of the individual's experiences]: An invalidating environment, in which an individual's emotional experiences are rejected, punished, or belittled, exacerbates emotional vulnerability. This can lead to difficulties in emotional regulation, and difficulty in forming an identity and interpersonal relationships.

Dialectical Dilemma: Linehan's theory also emphasizes the dialectical nature of BPD, where people oscillate between extremes, such as idealizing and degrading or devaluing others or themselves or experiencing intense love or hate. This dynamic reflects the internal struggle between opposing emotional and cognitive states.

Biosocial theory provides a comprehensive framework that not only explains the development of BPD but also paves the way for effective therapeutic interventions, especially DBT.

Object relations theory, rooted in psychoanalytic thought, focuses on internalized relationships and mental representations of significant others, called "objects." This theory has been applied to BPD to explain the intense and unstable interpersonal relationships characteristic of the disorder.

Splitting: A key concept in object relations theory is "splitting," where people with BPD tend to see others and themselves in extreme, black-and-white terms—either all good or all bad. This fragmentation leads to rapid changes in perception and intense emotional reactions.

Fear of abandonment: Object relations theory suggests that people with BPD struggle with an internalized fear of abandonment. This fear may stem from early life experiences where their caregivers were perceived as unreliable or inconsistent.

Distorted object relations: People with BPD may develop distorted or fragmented internal representations of others, leading to difficulties in maintaining stable and trusting relationships. Their interpersonal interactions are often characterized by intense dependency, fear of rejection, and difficulty managing interpersonal boundaries.

Object relations theory emphasizes the importance of early experiences and internalized perceptions of others in shaping the interpersonal difficulties seen in BPD.

Cognitive-behavioral theory (CBT) offers a more structured approach to understanding BPD, focusing on the role of cognitive distortions and maladaptive behaviors in maintaining the disorder.

Aaron Beck – Cognitive Therapy Developer, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, USA

Cognitive distortions: People with BPD often exhibit cognitive distortions, such as black-and-white thinking, catastrophizing, and overgeneralization. These distorted thinking patterns contribute to the emotional instability and impulsive behaviors characteristic of the disorder.

Behavioral reinforcement: CBT assumes that maladaptive behaviors, such as self-harm or drug use, are reinforced by the immediate relief they provide from emotional distress, even though they may have long-term negative consequences.

Schema Therapy: An extension of CBT, schema therapy focuses on identifying and changing deeply rooted and dysfunctional schemas – broad patterns of thinking and behavior that develop in response to early life experiences. In BPD, these schemas often revolve around themes of abandonment, mistrust, and worthlessness.

Cognitive-behavioral theory emphasizes the role of maladaptive thought patterns and behaviors in perpetuating BPD and provides a basis for therapeutic interventions aimed at cognitive restructuring and behavioral change.

The neurodevelopmental theory assumes that the roots of BPD may lie in the early development of the brain and nervous system. This theory suggests that disruptions in brain development during critical periods of growth can lead to the emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, and interpersonal difficulties that characterize BPD.

Brain structure and function: Neurodevelopmental theorists argue that people with BPD may have abnormalities in brain structures essential for emotional regulation and impulse control, such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex. These disorders may result from genetic factors, prenatal conditions, or early childhood experiences that disrupt normal brain development.

Brain plasticity: the theory also refers to the concept of brain plasticity – the ability of the brain to reorganize itself by creating new neural connections. In BPD, maladaptive thinking and behavior patterns may be reinforced by repetitive activation of certain neural circuits, making it difficult for people to regulate emotions or control impulses.

Developmental delays: Some proponents of the neurodevelopmental theory suggest that BPD may be related to developmental delays in the maturation of the brain's control systems. These delays can lead to difficulties managing stress, interpreting social cues, and maintaining stable relationships.

The neurodevelopmental theory emphasizes the importance of understanding the biological and developmental underpinnings of BPD, and emphasizes that early interventions may help moderate the impact of these neurodevelopmental disorders.

Trauma-informed theory focuses on the role of traumatic experiences in the development of BPD. This theory suggests that BPD may arise as a response to overwhelming stress or trauma, particularly during childhood.

Childhood trauma: Trauma-based theory emphasizes the high prevalence of childhood trauma among people with BPD. Experiences such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, neglect, and witnessing domestic violence are often reported by those diagnosed with BPD. The theory assumes that these traumatic experiences disrupt the proper development of the self and lead to difficulties in emotional regulation, identity formation and interpersonal relationships.

Complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD)

Some theorists see BPD as closely related, or perhaps even a form of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD). [C-PTSD is a condition resulting from prolonged exposure to traumatic events and characterized by a lack of emotional regulation, negative self-concept, and relationship difficulties. The overlap between C-PTSD and BPD suggests that BPD may be understood as a chronic response to trauma.

Dissociation and fragmentation: trauma-based theory also emphasizes the role of dissociation – a coping mechanism in which individuals disconnect from reality to escape the emotional pain of the trauma. In borderline personality disorder, dissociation can lead to a fragmented sense of self and reality, contributing to the intense emotional swings and identity disturbances characteristic of the disorder.

Trauma-based theory emphasizes the importance of treating the impact of trauma in the treatment of borderline personality disorder, and supports trauma-based treatment that recognizes the deep psychological wounds left by early negative experiences.

Social learning theory

The social learning theory, developed by Albert Bandura, emphasizes the role of learning through observation, imitation and modeling in the development of behavior and personality. This theory, applied to BPD, suggests that the disorder may stem from the learned behaviors and coping mechanisms observed and adopted during the formative years.

Albert Bandura – Canadian American psychologist

Modeling and imitation: According to social learning theory, people with BPD may learn maladaptive behaviors by observing significant others, such as parents or caregivers, who have exhibited similar patterns of emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, or unstable relationships. These behaviors are internalized and replicated in their lives.

Reinforcement and punishment: the theory also emphasizes the role of reinforcement and punishment in shaping behavior. For example, if a child's emotional outbursts or self-injurious behaviors are met with a lot of attention, these behaviors may become stronger and more frequent. On the other hand, if the expression of emotional needs is consistently ignored or punished, the person may learn to express emotions in extreme or dysfunctional ways.

Environmental influences: Social learning theory addresses the broader social environment, including peer influences, cultural norms, and media, in the development of BPD. People may adopt certain behaviors or beliefs about themselves and others based on the social context in which they grow up.

Social learning theory suggests that BPD can be understood as a set of learned behaviors and cognitive patterns, which can be learned or changed through therapeutic interventions that focus on building new and healthier behaviors and ways of thinking.

Conclusion

Borderline personality disorder is a multifaceted condition that cannot be fully explained by a single theory. The leading theories – biopsychosocial model, attachment theory, Linehan's biopsychosocial theory, object relations theory and cognitive-behavioral theory – each offer important insights into different aspects of the disorder. Together, these theories provide a comprehensive understanding of BPD, guiding both clinical practice and ongoing research. By integrating these perspectives, mental health professionals can better understand the complexities of BPD and develop more effective and personalized treatment plans for those affected by this challenging disorder.

The theories of neurodevelopmental learning, based on trauma and social learning each offer unique perspectives on the origins and mechanisms of borderline personality disorder. While neurodevelopmental theory emphasizes biological and developmental factors, trauma-based theory focuses on the profound impact of early negative experiences, and social learning theory emphasizes the role of environmental influences and learned behaviors.

Together with the theories discussed above, these perspectives provide a comprehensive understanding of BPD, paving the way for more diverse and effective treatment approaches. Understanding the diverse factors that contribute to borderline personality disorder is essential to developing personalized interventions that address the specific needs of people living with this challenging disorder.

There are quite a few who define borderline personality disorder as an identity disorder. Let's take a break here and discuss the concept of identity:

Lipiansky in his book "Identity in Psychology" writes:

"Identity can be considered a dynamic and integrative concept within the phenomenological and interactionist approaches. In this context, it can be considered both from a subjective point of view, with self-establishment or self-awareness, and from a relational point of view because self-awareness is a product of social interactions. It is clear that the construction of identity is a complex process; Each person is unique on the one hand and similar to others on the other hand (Lipiansky, 2008).

The concept of "self" can be described as involving an objective part corresponding to fixed characteristics (for example, age or sex) and a subjective part, the awareness of each person to be himself, that is, unique, and to be the same individual throughout his life.

(Lipiansky, E., M. (2008). L'identité en psychologie. In M. Kaddouri, C. Lespessailles, M. Maillebouis, M. Vasconcellos (dir), La question identitaire dans le travail et la formation (pp. 35-49). Paris: L'Harmattan.)

In general, 'identity' is used to refer to the social side or social 'face' of a person – the way they perceive how they are perceived by others while 'self' is generally used to refer to a sense of "who I am and what I am". However, these are not dualistic structures. Both the concepts of self and the concepts of identity develop out of and within social interaction.

(Millward L.M. and Kelly M.P. (2003a) 'Incorporating the biological: Chronic illness, bodies, selves, and the material world' in S. Williams, L. Birke and G. Bendelow (eds) Debating Biology: Sociological Reflections on Health, Medicine and Society, London, Routledge .)

The self is both individual and collective, both personal and social. It expresses membership in communities and is an immediate part of consciousness, "I am I".

It also includes a reflexive movement in which the individual tends to seek internal coherence, consistency and wholeness of existence. The self also includes idiosyncrasies or uniqueness but also similarity to others, to the individual and the social group, meaning it has objective and subjective perspectives, continuity and change.

(L'estime de soi; quelle valeur attribu-t-on à sa propre personne? How do you build self-esteem? Emeline Bardou, Nathalie Oubrayrie-roussel. In Press Concept-psy 27 Août 2014.)

(Lipiansky, E., M. (2008). L'identité en psychologie. In M. Kaddouri, C. Lespessailles, M. Maillebouis, M. Vasconcellos (dir), La question identitaire dans le travail et la formation (pp. 35-49).Paris: L'Harmattan.)

Lipiansky expands further on the construction of identity:

Building an identity, in which the self is built, is a long-term process that includes several sub-processes:

1] a process of individuation or differentiation that appears mainly in the first years of life through which the child manages to see himself as a distinct being;

2] a process of identification in which the individual appropriates characteristics of others, finds patterns and feels solidarity with certain communities;

3] an attribution process leading to the internalization of the images and the feedback coming from others;

4] Narcissistic evaluation process: the person is emotionally invested in himself;

5] A preservation process for continuity in time in self-awareness and providing a sense of permanence;

6] A process of understanding that identity cannot be reduced to perpetuating the past but rather opens up future possibilities through striving for an ideal and the fulfillment of life projects.

The above processes are dynamic and progressive, and do not have the same form and importance at different ages. The evolution of the sense of identity is far from linear, as there are changes related to experiences and life events. Finally, these processes seek to maintain homeostasis, which is a balance between diverse forces and influences on The individual. Identity is a search for self-definition and is built on the continuity of self-awareness despite the changes that occur all the time.

(Lipiansky, E., M. (2008). L'identité en psychologie. In M. Kaddouri, C. Lespessailles, M. Maillebouis, M. Vasconcellos (dir), La question identitaire dans le travail et la formation (pp. 35-49). Paris: L'Harmattan.)

According to Bardou and Oubrayrie-Roussel (2014), identity is a multidisciplinary system built around several dimensions: continuity, consistency (unity), evaluation (self-esteem), internal differentiation (sense of difference), external differentiation (desire for autonomy), assertiveness , originality (uniqueness) and resilience (coping).

(L'estime de soi; quelle valeur attribu-t-on à sa propre personne? How do you build self-esteem? Emeline Bardou, Nathalie Oubrayrie-roussel. In Press Concept-psy 27 Août 2014)

According to Cohen-Scali and Guichard, identity construction is the central theme of adolescence and emerging adulthood. This stems from a feeling of identity that develops over time through interaction with significant others in diverse contexts. However, this expected identity still has to be completed, changed and developed. Identity construction is not "monolithic".

First, it can vary significantly from one area of life to another. Thus, it seems that the idea of "achieved identity" is challenged. Second, the processes mobilized for identity construction appear to be much more complex than a particular combination of inquiry and commitment. The authors conclude that developmental approaches to identity lead to the perception of a "many" subjects (many selves) whose development processes are also many.

(Valérie Cohen-Scali, Jean Guichard. L'identité: developmental perspectives. L'Orientation scolaire et professionnelle, 2008, Identités & orientations – 1, 37 (3), pp.321-345.)

Now, we want to refer to our own model of mental life that we call Reference Group Focused Therapy (RGFT):

The model includes the "Primary Self" and the "Social Self” containing “Secondary Selves".

We will first refer to the primary self (Biological Predestined Core): the primary self consists of innate biological structures and instincts that form the innate basis of personality and cognitive processes. This primary self has its own dynamics during a person's life and is subject to changes with age, following diseases, traumas, drug consumption, addiction, etc.

Both the instincts and the basic needs in each and every person change according to different periods of development and aging – (hence their effect on behavior) and may change through drugs, trauma, diseases and more. Within the primary self there is the potential for instrumental abilities that are innate, but they can also be promoted, or on the contrary, suppressed through the influence of the reference groups that affect a person during his/her life.

The primary self also has cognitive abilities that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment during the first years of life. In addition, it includes the temperament and emotional intelligence that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment in the first years of life. And finally, it includes an energy charge that is mostly innate but can be suppressed through the influence of the reference groups, as well as through various situational factors.

The primary self also includes the six Individual Sensitivity Channels (ISC) which reflect our individual reactivity in response to stressors (both external and internal). So far we have identified six channels of sensitivity: 1. Sensitivity regarding a person's status and position (the Status Channel) 2. Sensitivity to changes in norms (the Norms Channel) 3. Sensitivity regarding emotional attachment to others (the Attachment Channel) 4. Sensitivity to threat (the Threat Channel) 5. Sensitivity for routine changes (Routine Channel) 6. Sensitivity to a decrease in energy level and the ability to act derived from it (Energy Channel).

From the primary self, a superstructure or "secondary selves" is developed through the interaction of the baby and later the person during his life with the figures around him, which is the "social self" of the individual consisting of the internalization of influential figures in his life, arranged in a hierarchical order [the group of these internalizations that we called metaphorically The Board of Internalized Figures" or the "Directorate of Internal Figures"] and there is a continuous dialogue between them and sometimes even conflicts, when one or more internalized figures have the greatest influence on the attitudes, feelings and behavior of the individual, whom we called the "leader – self" [ A figure formerly also called "the dictator – self", see previous conversations].

This leader or leaders can also impose a certain censorship about what will enter or will be expressed in the interrelationships in the board of internalized characters. We note that the events and characters in the external world maintain a kind of dialogue with the internalized characters and may affect the expression and sometimes even the hierarchy of the characters in the board of internalized characters.

In addition, it is possible that, similar to short-term memory, parts of which are transferred to long-term memory, also when it comes to the internalization of characters, there is a short-term internalization that, depending on the circumstances, the importance and duration of the character's influence, will eventually be transferred to a long-term internalization in the set of internalized characters.

The group of enemies is also found in the social self.

The "Internalized Enemy Group" is the place where the characters that threaten the person significantly are internalized and which the dominant characters in the characters’ directorate (leader-selves) prevent from entering and being internalized in the characters’ directorate [We assumed the existence of this group in the last year in light of thinking about the evolutionary need in the higher animals and up to the human in creating such a group in sake of their survival]. The characters in "The Internalized Enemy Group" are characters with negative emotional value. We note that usually the transition between the group of the Internalized Characters’ Directorate and the group of enemies is not common and even rare and usually happens following the traumatic or threatening event for a person.

Below is the structure of the board of internalized directors of the characters within the “social self”: This social self consists of "secondary selves" that include the following types: 1) a variety of "representations of the self" that originate from attitudes and feelings towards the self and its representations in different periods of life. These attitudes and feelings originate mostly from the subjectively perceived reflections of the internalized leader-selves about this particular person. These also include a reflective "I-representation" that has a certain and rather limited ability to observe human behavior and mental life. 2] Representations of internalized characters that originate from the significant characters that the person was exposed to during his life, but as mentioned, there may also be imaginary characters represented in books, movies, etc. that greatly influenced the person. 3] internalized representations of "subculture" [subculture refers to social influences in the environment in which a person lives and are not necessarily related to a specific influencing person]. We note that the individual is not aware that his actions, feelings and attitudes are caused by the dynamic relationships between these structured characters.

We will add that internalized key figures [usually human] in the board of directors, usually refer to the significant people in a person's life who played central roles in shaping his beliefs, values and self-concept. These figures may include family members, friends, mentors, teachers, or any other influential person who has left a lasting impression on the person's psyche.

Sometimes, these will also include historical, literary and other figures that left a noticeable mark on the person and were internalized by him. The term "internalized" implies that the influence of these key figures has been absorbed and integrated into the individual's thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors.

This internalization occurs through the process of observing, interacting with, and learning from these important people. As a result, the individual may adopt certain values, perspectives, and approaches to life that reflect those of the influential figures. These internalized figures can serve as guiding forces in decision-making, moral thinking and emotional regulation.

Figure: The model we propose for the structure of the psyche: the social self contains both the board of internalized figures and the internalized enemy group [which is not represented in this figure]

Having said this, we note that similar to the theories of object relations, we believe that in a newborn there is first a positive representation associated with a positive emotion for the figure of the caretaker and another representation if the same caretaker that is negative, associated with a negative emotion for the figure of the caretaker. These dual representations will gradually coalesce into one integrated representation over the next few years, a process that can continue until puberty and even beyond. In fact, we believe that it is the emotional component that enables the coalescence of a character or object into a negative representation around a negative emotion or into a positive representation around a positive emotion. We note here also that in disagreement with the object relations theorists we assume that “half-objects”, as we call them, will be centered around a face of the caretaker according to the data provided by the neuroscience in the recent years and not be some detached “partial objects” – “good and bad breast”, for example, as postulated by these theorists.

Why then was there an integration of these two into one representation? Why doesn't the opposite apply, more splitting for example into a negative emotion of anger and a negative emotion of sadness or depression, into a positive emotion of joy, or into a positive emotion of love and the like. Here we will answer that a variety of common features of the character contribute to the integration and combination of the negative and positive character. But there may be pathological cases such as those discussed below in borderline personality disorder, the split into a positive figure and a negative figure will remain in varying degrees, when the dominant emotion in the sufferer of the disorder brings up one or two representations.

Yet another case (of a multiple personality disorder), where an individual exposes splitting into many characters will be discussed in a separate article.

By the way, at the age of 8 months, a baby appears to be afraid of strangers, and we believe that at this stage, on the one hand, the "board of internalized characters" begins to form, along with another group that we call the "internalized enemy group" which concentrates mostly negative representations of the characters. At the age of 8 months, the representations of the new and unfamiliar people first pass to the internalized enemy group that begins to form at this stage, as a protective measure for an individual.

If the mother and her positive representation as the leading figure in the emerging board of characters appears with positive behavior towards the stranger, she can reduce the fear in front of a stranger with the statement like: "This is David Moshe, don't be afraid”, etc. If, on the other hand, the mother appears with rage and anger toward the stranger then there is a good chance that he will remain in the internalized enemy group. Basically, we say that the appearance of the fear of strangers heralds the appearance of the grouping of the negative character representations into the internalized enemy group and the grouping of the positive character representations into the internalized character board. As the years pass, an integration between the negative and positive representation of a given character will take place, the negative representation will coalesce with the positive and will remain among the board of internalized characters.

The "internalized enemy group" is therefore the place where the characters that threaten the person in a significant way are internalized and which the dominant characters in the character board (leader-selves) prevent them from entering and being internalized in the character board [We assumed the existence of this group in the last year in light of thinking about the evolutionary need in the higher animals and up to a human in the creation of such a group for their survival].

As mentioned, the characters in "The Enemy Group" are characters with negative emotional value. We note that usually after the integration phase into one character, the transition between the board group and the enemy group is not common and will eventually happen following the traumatic or threatening event for the person.

Now that we have presented the model containing the directorate of internalized characters and the group of internalized enemies, both of which appear in a person's social self, we will discuss the internalization of characters in BPD and its effect on the sense of identity and self-esteem, and more.

We assume that the integrative internalization of a human object includes its external properties (face, body shape and color, smell, typical non-verbal communication, voice) and its subjective characteristics (attitudes towards the world, the other person and the person himself), We then will have to expect that in the case of a person with BPD where the total integration and integration of the features of a given internalized character are impaired and thus the person suffering from this disorder will remain to a variable degree [depending on the depth and severity of the disorder] akin to a baby [see above] with one internalized representation with negative valence and a second internalized representation with positive valence.

In other words, it means that for each given external character in BPD, there will be one internalized representation related to the positive emotional valence that will appear in the board of internalized characters with some given subjective characteristics (attitudes towards the world, others , and especially towards the self) and at the same time there will be a second representation, in the internalized enemy group related to the negative emotional valence which will reveal quite different characteristics of subjective qualities.

However, we note that the external features of the two split representations may overlap. It is interesting to note that the finding of Paris [2002] mentioned above, that by the age of 40, most BPD patients no longer meet the criteria of the disorder, can hint at the hypothesis that the process of integration of the "half-characters" [with the opposite emotional valence] over the years in this disorder is not fundamentally defective and without the ability to correct, but it is an extremely slow process compared to the normal person so that it takes decades for his progress and even that is questionable as to where this progress touches. One possibility that could be discussed is the less pronounced excitability of the relevant limbic structures as the age progresses.

The question is, what consequences will the above mentioned processes have for a person with BPD? How will this affect his sense of self-identity? How will this affect his self-esteem? How will this affect his sense of inner security? How will this affect his communication with others and his social life?

First, we must examine the process of building self-identity from the point of view of the model we presented and the RGFT treatment method derived from it. In this model we assume that self-identity is closely related to self-image (which in the terminology of the model belongs to the secondary "self-representation"). This self-image is greatly influenced by the reference groups that a person meets during his life and internalizes them, the more significant the reference group is to the person and is internalized as significant, the greater will be its effect on the self-image.

In a "normative" case, these effects are more or less stable, the significant reference group (which can be associated with a single person or a group) that has been internalized transmits to the person according to its view its approach and relation to him his attitude to himself. This can be a supportive or repulsive attitude and it will respectively affect the person's self-esteem.

In the normative person, even if some of the internalized characters will have a negative attitude toward the person, there will be often a person or significant group internalizations exercising a supportive attitude, so that the effect will tend to be relatively balanced.

In the case of those suffering from BPD, the situation may be different. In extreme cases, very negative attitudes of an internalized character or an internalized group can be directed towards the patient.

For example, in one of our treatment cases, the mother figure internalized by the patient revealed her attitude to the patient with the following words: "I only regret not killing you while you were in the womb." In this particular case the internalized figure of the patient's sister also expressed similar negative emotional attitudes towards the patient. Not surprisingly, this particular patient made many suicide attempts. It seems that in this situation, the internalized mother's and sister's attitude in combination with the innate tendency not to develop sufficient neural connections between the opposing emotional brain systems or a lack of inhibition from the frontal lobe on the expressions of the amygdala exitation created an increased tendency to develop severe BPD.

We note that we believe that the more severe the BPD, the more polarized the two representations of the character or metaphorically the "half-characters", with the opposite emotional valence [positive or negative] in the brain. In the most severe cases, such "half-characters" will survive almost without internalized characters that incorporate the opposite emotional valence to one degree or another. In such cases, the "half-characters" with the negative emotional valence will lead to a rapid removal of positive emotions, which increases the probability of both depression and suicide attempts.

On the other hand, in less severe cases, frequent fluctuations in mood are expected related to the oscillating fluctuations of the influence of the internalized "half-characters" activated by the emotion that arises, following environmental stimuli such as the treatment of those around as perceived by the BPD sufferer.

Sometimes it will happen that in such cases the self-image will be fed by completely opposite messages from the internalized "half-characters", which will lead to an inconsistent and vague self-image, and as a result to a disturbance in the self-identity. However, in BPD patients with a higher level of organization, the splitting of the "half characters" [mainly that of the character with negative emotional valence] will be manifested only with the appearance of an external trigger that induces a strong and intense emotion in the sufferer of the disorder.

Now, impulsive behaviors such as unsafe sex, reckless driving, overeating, drug use or excessive spending and often exhibiting anger regulation problems, including frequent loss of temper or physical fights may be explained on two levels: First, hypofrontality [decreased frontal lobe activity in the brain] a feature described in BPD patients and as a result the decrease in impulse control. Second, a kind of compensatory behavior related to the appearance of anxiety states and negative emotions following the activation of the negative "half-character" representations.

We note that the fear of abandonment also plays a role in those suffering from this personality disorder. When left alone, the influence of the negatively valued internalized "half-characters" can overwhelm them, resulting in overwhelming feelings of anxiety and despair. The presence of someone near them (if not perceived as hostile) may improve these feelings, and satisfy the never-ending longing for attachment (we note that the persons with BPD are very sensitive in the attachment channel). Perhaps this overly sensitive attachment channel is correlated with the tendency for certain brain nerve connections not to be developed enough (which may perhaps be reflected in the defects documented in frontolimbic connections in brain imaging).

In RGFT, treatment often involves identifying these internalized characters and exploring how they affect the person's current behavior and state of mind. By bringing these influences into awareness, people can begin to change unhelpful or negative aspects of these internalized characters, allowing for more conscious and healthy choices in their thoughts and behaviors.

Finally, let's summarize things as a short resume in the context of a case of severe and deep borderline personality disorder using an expanded RGFT model that includes the "internalized group of enemies" within the social self.

Introduction

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is a very complex and challenging mental condition characterized by emotional instability, impulsive behaviors, identity disturbances and turbulent relationships. The extended Reference Group Focused Therapy (RGFT) model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding BPD by conceptualizing the "social self" as a hierarchy of internalized significant figures, organized into a "directorate" or "board" of internalized figures. The recent addition of an "internalized enemy group" in the social self, where negative representations of key figures are stored, further enriches this model and offers a new perspective on the duality of internalized representations in borderline personality disorder.

The “directorate of internalized characters” and the “internalized enemy group” in a person with BPD.

In the extended RGFT model, each internalized key figure in the psyche of the BPD sufferer has two separate representations:

1. Positive representation: This representation exists within the board of internalized characters, which affects the individual's self-perception, behaviors and emotional reactions in a positive or adaptive way in general.

2. Negative representation: This resides in the internalized group of enemies, which exerts a harmful influence, often contributing to self-destructive behaviors, negative self-perceptions, and maladaptive emotional reactions.

These dual representations are not static; They can be activated depending on the circumstances and emotional context, leading to the emotional volatility and identity disturbances seen in BPD.

Dual representations and emotional instability in borderline personality disorder

Running double representations:

In people with BPD, the activation of the positive or negative representation of an internalized figure depends on the external circumstances and their emotional impact:

Positive activation (in the board): When the circumstances match the individual's expectations or when he feels validated, supported or loved, there is the activation of the positive representation from the board. This can lead to feelings of confidence, self-worth and emotional stability.

Negative activation (the enemy group): On the other hand, when the individual perceives criticism, rejection or a threat – whether real or imagined – there is activation of the negative representation in the internalized enemy group. It can trigger strong emotions such as anger, fear or self-loathing, leading to impulsive behaviors or emotional outbursts.

The rapid transition between these representations contributes to the emotional instability characteristic of borderline personality disorder. For example: a person with BPD may feel very connected and loved when their partner shows affection (activating the internalized positive representation of the partner in the internalized characters’ directorate). However, a small look – which will be perceived as an indifferent and delayed response to the sentence of the BPD sufferer – can immediately activate the negative representation of that partner in the enemy group, and lead to feelings of betrayal, anger or abandonment.

This "emotional whiplash" occurs because the individual's emotional state is greatly affected by one of the opposing representations currently being activated, resulting in rapid and intense mood swings that are often difficult for others to understand.

Identity disorder and the dual representation model

fragmented sense of self:

The existence of dual representations of one character within the board and one in the enemy group contributes to the fragmented sense of self often observed in BPD. The individual's self-concept may be deeply influenced by which representation is dominant at a given time:

Positive self-image: When the positive characters in the board of internalized characters are dominant, the individual may see himself as capable, loved and worthy. This may manifest in more adaptive behaviors and healthier relationships.

Negative self-image: However, when the negative self-image representations in the enemy group take over, the individual may see himself as fundamentally flawed, unworthy, or doomed to rejection. This negative self-view can drive self-harming behaviors, such as self-harm, substance abuse, or sabotaging relationships.

Internal conflict and self-contradiction:

The coexistence of these dual representations within the individual can lead to a constant internal struggle, as the positive and negative self-concepts struggle for control. This can cause self-contradiction, where the individual may express contradictory beliefs about himself or others, sometimes even in rapid succession. For example, they may alternate between idealization and devaluation of that person or aspect of themselves, reflecting the internal conflict between the principal and the enemy group.

Relationship dynamics in BPD using the dual representation model:

Splitting in relationships

The phenomenon known as "splitting," in which people with BPD see others in extremes (either good or bad), can be understood through the lens of dual representations. Each significant person in the individual's life may have both a positive and a negative internalized version:

Idealization: During periods of idealization, the positive representation of the significant other in the board of internalized characters is dominant, leading to feelings of intense admiration and strong attachment.

Devaluation: However, any perceived threat or disappointment can quickly shift dominance to a negative representation of the significant other in the enemy group, resulting in marked devaluation, anger, or withdrawal.

This rapid shift from idealization to devaluation in relationships is the hallmark of BPD and is deeply rooted in the activation of these dual internalized character representations.

Fear of abandonment

The fear of abandonment, which is central to borderline personality disorder, is also intricately related to the dual representation model:

Positive representation: When the positive image is in control, the individual may feel secure in their relationships and able to maintain closeness.

Negative representation: However, any slight indication of potential abandonment can activate the negative image representation, increasing fears and leading to frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined rejection.

This duality explains why people with BPD may simultaneously crave intimacy and alienate others, as they oscillate between the security provided by the board of internalized characters and the terror evoked by the enemy group.

Trigger event analysis (TEA) and dual representations

Sensitivity and activation channels:

The six sensitivity channels identified in Trigger Event Analysis (TEA) can be directly related to the activation of the internalized board or the internalized enemy group:

• Status: A change in status may trigger the positive or negative representation, depending on whether the change is perceived as a gain or a loss. For example, a promotion may trigger a positive self-concept, while a demotion may trigger a negative one, leading to feelings of inadequacy or anger.

• Norms: Conflicts with group norms can change the dominance between the board and the enemy group, depending on whether the individual feels approved or rejected by the group.

• Attachment: Changes in attachment relationships are particularly strong triggers for borderline personality disorder, often driving the individual between positive and negative representations of significant others.

• Threat: Any perceived threat to survival, whether physical, emotional, or financial, may activate the negative representations in the enemy group, leading to increased anxiety and defensive behaviors.

• Routine: disruptions in routine can destabilize the individual, and may transfer control to negative representations, especially if the routine is associated with a sense of security or control.

• Energy: physical or emotional exhaustion can lower the threshold for the negative representations to take over, and worsen emotional dysregulation and impulsivity.

Therapeutic implications of the expanded model

Balance between the board and the enemy group:

Therapeutic interventions in RGFT can focus on helping people with BPD recognize and understand the duality of their internalized figures. The goal will be:

• Identify and differentiate: help a person identify when the negative representations from the enemy group are activated and differentiate them from the positive representations in the internalized board.

• Challenge and integration: act to challenge and reduce the dominance of the negative representations of the enemy group and combine them with the perceptions of the positive representations in the internalized board.

• Coping strategies: develop coping strategies that help the person manage the rapid transitions between these representations, such as mindfulness techniques, or cognitive restructuring.

TEA can be used as a diagnostic tool to identify which sensitivity channels are most prone to trigger changes between the board and the enemy group. This analysis can guide treatment by highlighting specific areas where the individual is most vulnerable and where intervention is most needed.

Conclusion

The extended model of reference group-focused therapy (RGFT), which incorporates the concept of an internalized enemy group, provides a powerful framework for understanding the complexities of borderline personality disorder. By recognizing the existence of dual representations for each internalized key figure – one positive in the internalized board and one negative in the enemy group – this model explains the intense emotional instability, identity disturbances and relationship difficulties that characterize borderline personality disorder.

Therapeutic interventions based on this model can offer new ways to help people with BPD achieve greater emotional stability, a more coherent sense of self, and healthier interpersonal relationships.

That's it for this time,

yours,

Dr. Igor Salganik and Prof. Joseph Levine

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Leave a comment