Conversation 61: Extending the model of the self that stands behind RGFT

Hello all

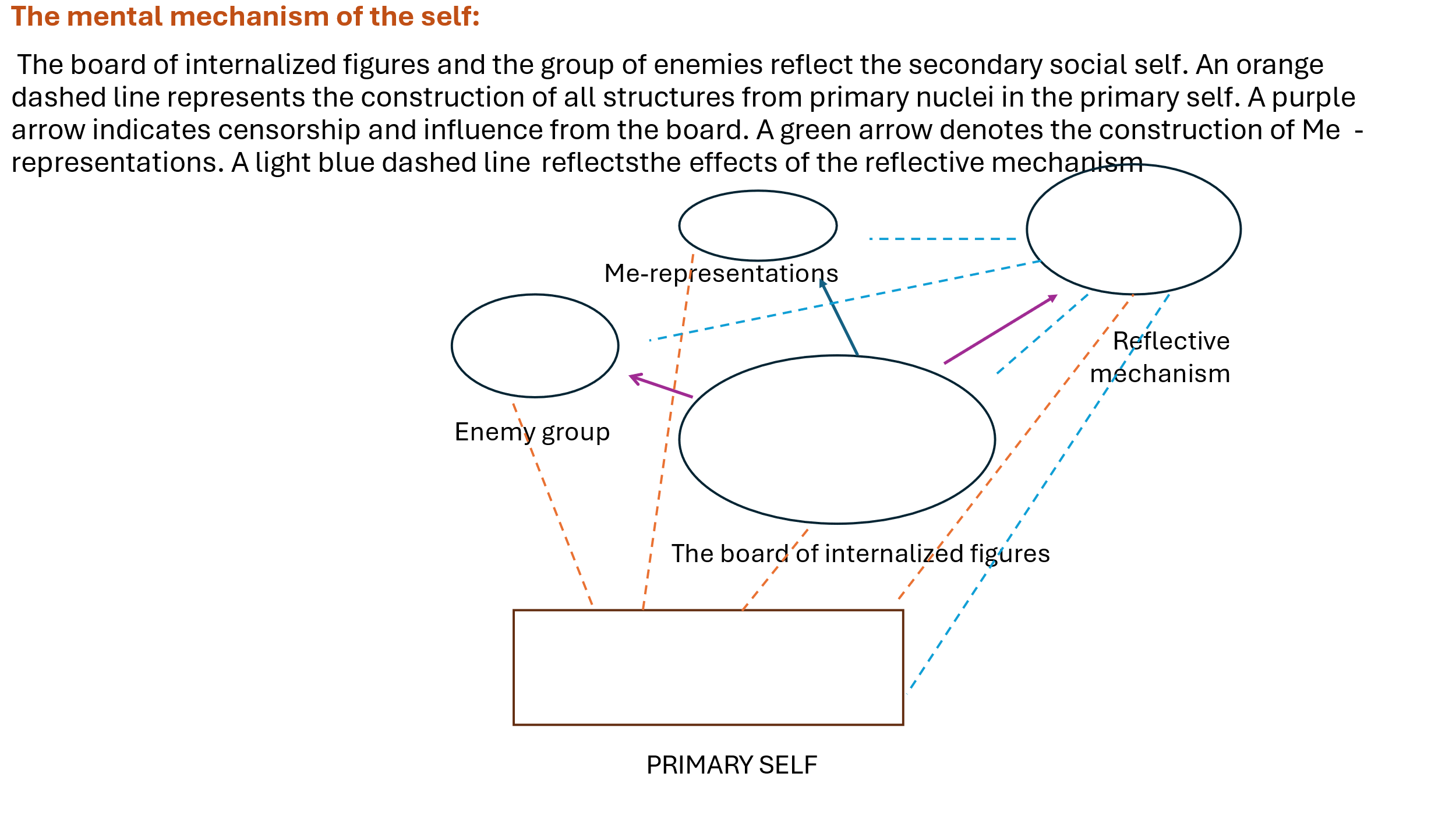

In our model, the self includes the elements of the human psyche. The model first assumes the existence of the "primary self", which is in fact the basic biological core consisting of several innate structures and subject to development during life, this self includes the instinctive emotional and cognitive parts of the person. The primary self uses the reservoirs and mechanisms of emotion, memory and cognitive abilities and it contains primary nuclei for the future development of other mental structures.

Let's first refer to the primary self (Biological Premordial Core): the primary self consists of innate biological structures and instincts that form the innate basis of the parts of the personality and it also included the cognitive processes and the emotional processes. This primary self has its own dynamics during a person's life and is subject to changes with age, following diseases, traumas, drug consumption, addiction, etc. Both the instincts and the basic needs in each and every person change according to different periods of development and aging – (hence their effect on behavior) and may change through drugs, trauma, diseases and more. Within the primary self there is the potential for instrumental abilities that are innate, but they can also be promoted, or on the contrary, suppressed through the influence of the reference groups. The primary self also has cognitive abilities that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment during the first years of life. In addition, it includes the temperament and emotional intelligence that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment in the first years of life. And finally, it includes an energy charge that is mostly innate but can be suppressed through the influence of the reference groups, as well as through various situational factors. The primary self also includes the six personal sensitivity channels: Individual Sensitivity Channels (ISC) which reflect our individual reactivity in response to stressors (both external and internal). So far we have identified six channels of sensitivity:

- Sensitivity regarding a person's status and position (status channel)

- Sensitivity to changes in norms (norm channel)

- Sensitivity regarding emotional attachment to others (attachment channel)

- Sensitivity to threat (threat channel)

- Sensitivity for routine changes (routine channel)

- Sensitivity to a decrease in energy level and the ability to act derived from it (energy channel)

From the initial self, they continue to develop from innate nuclei that constitute a primordial basis for development in the interaction of the baby and later the person during his life with the figures in his environment and the events of reality. Consequently, a number of superstructures is developed:

1] The reflective agency,

2] Three structures that together make up the secondary self or the social self, these include:

A] The group of internalized characters that we will metaphorically call the Board (or Directorate) of Internalized Characters,

B] Enemies’ group

C] A group of Me-representations.

The reflective agency

Now we will note that from the primary self, a structure arises and is built from a particular nucleus at birth, which we will call the reflective agency whose function is to review and observe the systems of the psyche as detailed below. This mechanism has the function of evaluation and is also related to the interpretation of the events of reality and the events of the inner mind. See Appendix A for thoughts about the reflective agency.

The group of the internalized characters that we will metaphorically call the “board of internalized characters”

The board of internalized figures consists of the internalization of influential figures in one's life, arranged in a hierarchical order [as mentioned, we metaphorically call the group of these internalizations the board of internalized figures or the board of internal figures]. These characters have a continuous dialogue between them and sometimes even conflicts, while one or more internalized characters have the greatest influence on the individual's attitudes, feelings and behavior, which we called the "leader self" [a character formerly also called the "dictator self", see previous conversations].The attitudes of the inner leader play a central role in making decisions about the internalization of information and figures. He decides whether to reject the internalization or, if accepted, in what form it will be internalized. In other words, in a sense, we assume that this influential figure is also a form of internal censorship. It should be emphasized that these are not concrete hypotheses regarding the presence of internalized figures in the inner world of the individual as a sort of "little people inside the brain", but rather it’s about their representation in different brain areas whose nature and manner of representation still requires further research. We will also note that although we call this figure the "inner leader", with the exception of a certain type, its characteristics are not the same as those of a ruler in a particular country, but rather that this figure is dominant and influential among the "directorate of figures".

AI assisted illustration: Board of Internalized Characters. The bigger figure expresses the internalized inner leader

We note that the events and characters in the external world maintain a kind of dialogue through the mediation of the reflective agency [We will detail it later] with the internalized figures in the board [or with the enemies’ group – see below] and may or may affect the expression and sometimes even the hierarchy of the figures in the board of internalized figures. In addition, it is possible that similar to short-term memory, parts of which are transferred to long-term memory, also when it comes to internalizing figures into the brain, it is feasible that initially there is a short-term internalization, which, depending on the circumstances, importance and duration of the character's influence, will eventually be transferred to a long-term internalization in the set of internalized characters.

Below is the structure of the board of internalized characters: This board consists of "secondary characters" which include the following types: 1] Representations of internalized characters that originate from the significant characters that the person was exposed to during his life, but as mentioned, there may also be imaginary characters represented in books, movies, etc. that greatly influenced the person; 2] internalized representations of "subculture" [subculture refers to social influences in the environment in which a person lives and are not necessarily related to a specific person]. We note that the individual is not aware that his actions, feelings and attitudes are caused by the dynamic relationships between these structured characters.

We will add that internalized key figures in the board of directors [usually human], usually refer to the significant people in a person's life who played central roles in shaping his beliefs, values and self-concept. These figures may include family members, friends, mentors, teachers, or any other influential person who has left a lasting impression on the person's psyche. Sometimes, these will also include historical, literary and other figures that left a noticeable mark on the person and were internalized by him. The term "internalized" implies that the influence of these key figures has been absorbed and integrated into the individual's thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors. This internalization occurs through the process of observing, interacting with, and learning from these important people. As a result, the individual may adopt certain values, perspectives, and approaches to life that mirror those of the influential figures. These internalized characters can serve as guiding forces in decision-making, moral thinking and emotional regulation. See Appendix B for thoughts about the collection of internalized characters.

“Enemies’ group”

Now we will note in addition that from the primary self there arises and is built from a hypothetical nucleus at birth a structure that we will call the enemies’ group. So in addition to the board of internalized characters in the social self there is also the "enemies’ group" and more precisely the "internalized enemies’ group" This is the place where the characters that are perceived as significantly threatening the person are internalized and which the dominant characters in the internalized characters’ directorate prevent from entering and being internalized in the characters’ directorate [We assumed the existence of this group last year in light of the evolutionary need in animals for their survival, see a broad reference to the subject of enemies below]. The characters in the "enemies’ group" are characters with a negative emotional value and are represented schematically relative to the characters in the board of internalized characters. We note that usually the transition between the group of the board of internalized characters and the enemies’ group is not common and even rare and usually happens following the traumatic or threatening event for a person. As mentioned later in Appendix C, we will present a discussion and thoughts on concepts and theories related to the perception of the enemy.

A group of Me-representations

In addition, from the primary self, as mentioned, a superstructure of Me-representations develops in the different periods of life [for example, the representation of the Me as a child,as a teenager,as an adult and more] including the bodily representation. The representation of the Me in a certain sense is about a kind of container for the flow of information of emotional attitudes and behaviors from the dynamics in the board of characters into it. See Appendix D for thoughts about the group of Me-representations.

Below we will bring again the illustration of the model of the self that includes the structures mentioned above and the mutual interactions between them:

When we say this we should note that, like the theories of object relations, we believe that in the newborn baby there is first a dual representation of a primary caregiver (or caregivers), where his (their) positive representation will be associated with a positive feeling awoken by the character [or characters] and the negative representation will be associated with negative emotion provoked by the character (s). These dual representations will gradually merge into one integrated representation over the next few years. In fact, we believe that it is the emotion that allows the convergence of character’s features to a one-sided figure within a framework of a dual character’s representation – a negative figure representation around negative emotions and positive figure representation around positive emotions [see Appendix on the emotion and its unifying and cohesive activity]. Why, then, during a normal child’s development these two opposing character representations merge later in life in just one representation? Why is there not even more fragmentation, for example, for a negative feeling of anger and a negative feeling of sadness or depression, for a positive feeling of joy, or for a positive feeling of love, etc.? Here we assume that a variety of shared features of the character aggregates around a representation of the character’s face [see previous conversations] and this contributes to the integration of the dual character representation into a single internalized character. But there may be pathological cases, as in borderline personality disorder (see previous blog), where the split will persist maintaining a positive and negative character in varying dimensions, where the emotion controlling the disorder raises one or the other representation to consciousness. By the way, at the age of 8 months or so, when a baby develops a fear of strangers for the first time it could be also a time point where the emerging “board of internalized characters” will start to differentiate itself from another group that we call the “enemies group” where the internalized figures are united by a considerable negative emotion associated with them. At the age of 8 months, it is common that new and unfamiliar people are at first perceived as threatening (probably moved by default into an emerging enemy group) and only if the mother exhibits positive behavior towards a stranger (assuming that she herself is internalized as the leader self within the baby’s emerging directorate of internalized characters) by saying for example: “This is David Moshe, don't be afraid”, and so on, a person will be taken out of the enemy group. As mentioned above, the characters in the “group of enemies” are characters with negative emotional values. It should be noted that the transition between the board group and the enemy group is usually rare and costly due to the traumatic or threatening event usually accompanying it.

We hypothesize that the board of internalized characters usually completes its development during adolescence as well as the reflective agency that gradually develops and reaches a significant completion with adulthood but can continue to develop further during the rest of life. Similar to the representation of the mother initially in the infant as positive or negative [emotionally], the representation of the Me develops from a primordial nucleus in the primary self, which is also initially apparently dual and includes a positive and negative representation.

The interrelationship between the emotion, its quality and intensity and the structures of the model

Each of the characters in the directory of internalized characters carries with it not only attitudes and behaviors but also feelings [note that the location of cognitive abilities as well as feelings and basic behaviors is in the primary self].. Thus, when a certain character or characters act within the dynamics of the board of directors, these emotions are activated. The same is true for the group of enemies, that when it is activated, the negative feelings associated with the character or characters internalized in it rise. The nature of the emotion depends on the character and the empowerment depends on the position of the character in the dynamic hierarchy and the dominance of its action at that time. One of the main reasons for activating characters is the flow of reality events as interpreted in the reflective agency when the magnitude of the importance given by the reflective agency is related to the magnitude of the accompanying emotion. This information from the reflective agency to these groups will activate different characters with their accompanying emotions. At the time of extraordinary reality events that sometimes the reflective agency is overwhelmed by them and cannot interpret or analyze them, there is a massive activation of certain characters with their accompanying emotions. Sometimes in such a powerful flood as during a traumatic event, it is even possible that a new internalized character emerges that becomes dominant and pushes behind the previous leader or leaders with a strong side effect. Me-representations are also affected, as we hypothesize that they are containers for the effects of the board of characters and the enemies’ group, and the reflective agency, and this information flow will determine the type and magnitude of the effect. Finally, feelings generally have a stimulating and unifying effect on the systems of the mind. We note that the sensitivity channels in the primary self also activate mainly negative emotions, as well as impulses and instincts in the primary self. Finally, we will emphasize that, as a rule, emotions have a stimulating and unifying effect on the systems of the mind. [See Appendix H].

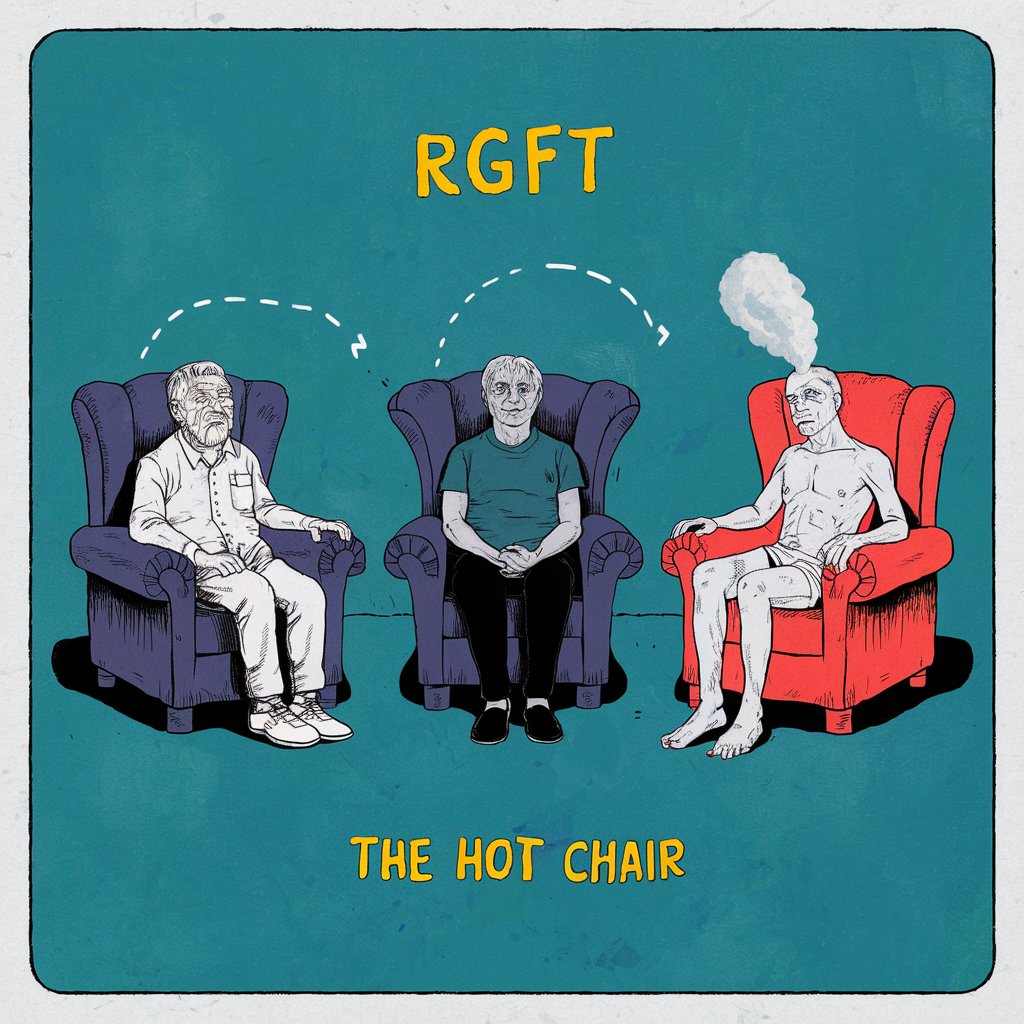

Reference Group Focused Therapy (RGFT) -brief discussion

RGFT is a psychotherapeutic technique that emphasizes understanding and addressing the influence of internalized reference groups on people's psychological state. These reference groups usually consist of significant figures from the person's past, such as family members, teachers or friends, whose attitudes, behavior and expectations have been internalized and continue to unconsciously influence the person's feelings, thoughts and behavior.

Treatment with RGFT often involves identifying these internalized characters and examining their impact on the person's current behavior and mental state. By bringing these influences into conscious awareness, people can begin to part with unhelpful or negative aspects of these internalized characters, allowing for more conscious and healthy choices in their thoughts and behavior.

AI assisted illustration: The internalized characters that influence a person's behavior and mental state

Our approach is different from other approaches, such as Jungian therapy, which focuses on universal archetypes, or Gestalt therapy, which emphasizes the present moment and the integration of different parts of the self. RGFT focuses more on historical and social contexts that shape a person's identity and behavior [see previous blogs and video chat no. 36 on YouTube under the title “SALGANIK & LEVINE" regarding the treatment of RGFT]. Finally, RGFT therapy also assesses and attempts to address one's sensitivity channels.

Demonstration of a significant element in treatment with RGFT by AI: on the left the therapist : in the middle the patient himself : on the right the patient after moving to the hot chair and now speaking in the first person as one of the dominant internalized figures in his psyche [see video blog 36 for the explanation of the treatment technique]

Below we will provide several appendices of thoughts about the reflective agency, the board of internalized characters, the enemies’ group, the Me-representations. and the role of emotions as a unifying force that captures and activates components in these structures. The appendices bring various general aspects regarding these structures and topics with an emphasis on the brain mechanisms involved in their activity. These appendices were written, among other things, with the help of AI while asking specific questions, using additional sources and rechecking to verify evidence and statements.

Appendix A

Thoughts about the reflective agency

The reflective agency in the mind

The reflective agency refers to one's ability to reflect on and evaluate personal thoughts, feelings, and identity. This process is primarily supported by a network of brain regions, including the middle prefrontal cortex (mPFC), the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), and the precuneus. These areas are part of the default brain network (DMN), which is involved when people engage in self-referential thinking.

- The middle prefrontal cortex (mPFC):The middle prefrontal cortex is essential for evaluating self-related information, integrating personal experiences, and maintaining a coherent sense of self over time.

- Posterior singulate cortex (PCC) and parcuneus: These areas contribute to introspection and self-awareness, helping to process autobiographical memories and maintain an enduring sense of personal identity.

This network of self-reflection is essential for internal monitoring of one’s thoughts, behaviors, and emotions, and affects decisions and actions in social contexts. It also interacts with the brain’s emotional regulating centers, such as the amygdala and the frontal-lobe, and regulates emotional responses to personal experiences.

In our view, this reflective agency also interprets the events of external as well as internal reality.

Appendix B

Thoughts about the board of internalized characters in the brain

Internalized human figures represent people who played a significant role in shaping their identity and behavior. These figures, such as influential parents, mentors, or colleagues, are encoded in the brain through memory-based emotional, sensory, and cognitive networks. The brain regions involved in the internalization and representation of these figures include:

- The middle prefrontal cortex (vmPFC):This area is involved in processing emotional experiences and moral reasoning. Internalized characters often influence one's moral judgments and behavioral decisions, as the vmPFC integrates information about past interactions and emotional connections.

- Anterior Temporal Lobe (ATL):It is critical for storing social knowledge, including representations of significant others. It helps encode long-term memories of social interactions, and allows people to summon the guidance or values imparted by internalized figures in decision-making processes.

- Hippocampus: The hippocampus plays a role in forming memories, especially autobiographical memories involving significant others. It helps create detailed memories of past experiences with internalized characters, influencing future interactions and emotional responses.

These areas work in tandem to create mental simulations of how internalized characters might react or judge current behavior, shaping moral and ethical behavior and emotional reactions.

As a rule, the representation of human figures in the brain is a complex process involving multiple regions and networks working together to perceive, recognize and understand the human form, actions and emotions. This process is central to social cognition, allowing humans to interact, identify and communicate with each other. This is how human figures are represented in the brain:

1. Visual perception of human figures

The perception of a human figure begins in the visual cortex, located in the occipital lobe. The primary visual cortex (V1) processes basic visual information, such as shapes, edges, and motion. However, human figure recognition specifically involves higher-order visual areas, particularly the fusiform eminence and the extrastriate body area (EBA).

Fusiform facial area, or FFA:

This region, located in the temporal lobe, is critical for recognizing faces and other detailed visual features of humans. The FFA responds selectively to human faces but also shows some activity when viewing the whole human body or body parts, although it is highly specialized for face recognition.

Extrastriate Body Area (EBA):

The EBA, located in the lateral occipitotemporal cortex, is specifically involved in the visual recognition of human bodies and body parts (eg, arms, legs) as distinct from other objects. It is activated when people perceive human shapes and figures, even when the face is not visible.

This area helps distinguish between living and inanimate objects, ensuring that the brain correctly recognizes human figures even in low-detail representations such as silhouettes or stick figures.

Understanding and recognizing actions (action representation)

The perception of human figures is not limited to static images; The brain must also recognize and interpret the actions and movements of others. This is largely supported by the mirror neuron system and areas responsible for motor processing.

The premotor cortex and the mirror neuron system:

Mirror neurons, located primarily in the premotor cortex and inferior parietal lobe, fire both when a person performs an action and when they watch someone else perform the same action. This system helps us understand the movements and intentions of others by simulating their actions in our motor system.

This system plays a crucial role in social cognition and empathy, as it allows us to "reflect" and interpret the actions of others. For example, when you watch someone reach for an object, your brain engages in similar motor planning to understand the intention behind the action.

Superior temporal sulcus (STS):

The superior temporal sulcus, located in the temporal lobe, is critical for decoding biological motion and is particularly sensitive to the movements of human figures. It processes information about where a person looks, his gestures and general body movement, and contributes to understanding social cues and intentions.

Superior temporal sulcus also plays a role in detecting complex social interactions, such as detecting whether two people are communicating with each other or understanding group dynamics.

Emotion recognition and empathy

Beyond recognizing the person's character and actions, the brain must also interpret the feelings and mental state of others, which include areas that specialize in social cognition and emotional processing.

Amygdala:

The amygdala is involved in emotional processing and plays a crucial role in recognizing emotions from human faces and body language. The amygdala is sensitive specifically for detecting emotions such as fear, anger or happiness, allowing the brain to quickly assess potential social or environmental threats.

The middle prefrontal cortex (mPFC):

The middle prefrontal cortex is involved in higher-level social cognition, such as understanding the mental states and intentions of others (often called theory of mind). It helps to interpret the thoughts, beliefs and feelings of others, which is the key to empathy and understanding human characters not only as physical entities but as emotional and purposeful entities.

Insula and empathy:

The insula plays a role in emotional awareness and empathy, especially feeling the emotions of others. When we observe someone in pain or distress, the insula becomes active, allowing us to "feel" their emotions to some extent. This process is essential for interpreting the emotional states of human characters in social interactions.

Facial recognition and social identity

Human face recognition is a critical component of social interaction and is processed in a very special way by the brain.

Fusiform facial area (FFA):

As mentioned, FFA specializes in face recognition. It responds selectively to them, allowing us to recognize people, recognize emotions, and interpret social cues. This domain is essential for understanding facial expressions, eye contact and other critical aspects of human interaction.

Occipital facial area (OFA):

Located in the occipital lobe, OFA works in conjunction with FFA and the superior temporal sulcus (STS) to process facial features such as eyes, mouth, and nose. While the FFA is more specialized in face recognition, the OFA processes the visual elements that make up the face.

Body language and non-verbal communication

Human figures convey a lot of information through body language and posture, even without speaking. The brain is adept at reading these nonverbal cues, which often communicate emotions, intentions, and social status.

The parietal cortex:

The parietal lobe, especially the inferior parietal lobe, is involved in processing spatial orientation and body position. It helps us understand the postures and gestures of others in relation to their environment, and allows us to interpret physical cues that indicate someone's attention, intent or mood.

Integration of multisensory information

The brain does not process human figures only based on visual information. Instead, it combines data from multiple senses to create a complete representation of another person. For example, seeing someone move, hearing their voice, and interpreting their posture all contribute to the brain's representation of that person.

Areas of the superior colliculus and multisensory integration in the brainstem and cortex help integrate visual, auditory, and tactile information to create a coherent understanding of the human figure in real time.

The brain representation of human figures thus includes a network of areas that work together to recognize faces, body parts, and actions; understand intentions; interpret feelings; and process social interactions. Critical areas such as the fusiform prominence (face recognition), the extrastriate body area (body recognition), the mirror neuron system (action understanding), and the amygdala (emotion processing) all contribute to this complex and essential function of social cognition. This ability allows humans to successfully navigate the social world, to understand others not only as physical beings but as emotional and purposeful beings.

Appendix C

Thoughts about the enemies’ group

Representing the enemy refers to how the brain perceives and responds to individuals or groups perceived as hostile or threatening. This representation is associated with fear, aggression and defensive behaviors, which involve several key areas of the brain:

Amygdala: Central to threat perception, the amygdala is hyperactive when people see or think about perceived enemies. It triggers emotional reactions such as fear and anger, which prepare the body for fight or flight reactions.

Anterior singulate cortex (ACC):The ACC is involved in processing conflicts, both internal and external. When a person encounters an enemy or experiences a moral dilemma involving an enemy, the ACC helps regulate emotional responses and decision making.

Orbitofrontal cortex (OFC):The OFC is critical for evaluating the consequences of actions. In the context of enemy representations, it helps regulate responses to perceived threats by weighing the social, emotional, and moral consequences of aggression or hostility.

These brain regions are heavily involved in shaping an individual's responses to enemies, including aggression, fear, and defensive behaviors. They are often in a state of increased activation during times of conflict or stress, which increases negative emotional responses.

Representation of enemies in the brain

The term "enemy representation in the brain" refers to the way our brain processes and perceives those we perceive as threats or adversaries. This cognitive and neurological phenomenon is studied in various fields, including psychology, neuroscience and social cognition. Some key points include:

1. Social cognition and threat perception

The brain has developed mechanisms to quickly identify potential threats. The amygdala, part of the limbic system, is essential for identifying emotionally salient stimuli, especially threats. When a person perceives another person as an "enemy", the amygdala is activated, triggering feelings of fear, aggression or heightened vigilance.

Bias and categorization: The mind tends to categorize people into "in-groups" and "out-groups" based on cultural, social or political lines. Perceiving someone as part of an "outgroup" can evoke negative feelings or stereotypes, which contribute to the perception of the enemy.

Dehumanization

Studies have shown that when people see their enemies, especially in conflict situations, they may dehumanize them, seeing them as less human or less deserving of empathy. It is believed to involve areas of the brain such as the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which are involved in social thinking and empathy. Reduced activity in this area can be related to seeing others as less human.

Circles of fear and aggression

Fight or flight responses are deeply rooted in human evolution. When faced with an "enemy", the brain's fear and aggression circuits are activated. The hypothalamus and amygdala trigger the release of stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline, preparing the body to deal with the threat.

Aggressive reactions toward enemies are also mediated by these circuits, with inputs from the prefrontal cortex (involved in higher thinking) helping to regulate aggressive impulses.

The role of the prefrontal cortex

The prefrontal cortex(PFC), which is responsible for rational thinking, decision making and impulse control, plays a vital role in regulating responses to perceived enemies. While the amygdala may initiate an emotional response, the PFC can help reframe the situation, which may reduce aggressive or fearful responses. In situations where conflict resolution or diplomacy is possible, the PFC helps people see "enemies" as human beings with intentions, emotions, and rationality.

Empathy and perspective taking

The ability to empathize and take the perspective of others involves a network of brain regions, including the temporal-parietal junction (TPJ) and the medial prefrontal cortex. When one does not take the enemy's point of view, empathy is reduced, and this can escalate conflicts.

Research suggests that increasing empathy or understanding the "enemy's" perspective can help de-escalate conflicts, so empathy-promoting interventions are often effective in peacebuilding efforts.

Neurological studies

Brain imaging methods such as fMRI have been used to study how the brain reacts to images, statements or actions of the enemy. In these studies, increased activity in threat-processing regions (such as the amygdala) was typically observed when people were exposed to stimuli representing their enemies, whether real or imagined.

Understanding how the brain represents enemies offers insights into social conflict, aggression and peacebuilding. By understanding these processes, interventions aimed at de-escalation, perspective-taking and empathy can be developed.

Here are some key manuscripts and studies discussing enemy representation in the brain, threat perception, dehumanization, and related neural mechanisms:

Amodio, DM, & Devine, PG (2006)."Stereotyping and evaluation in implicit race bias: Evidence for independent constructs and unique effects on behavior." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4), 652–661.

This study discusses how implicit biases, which can contribute to enemy perception, are represented and processed in the brain, specifically focusing on the amygdala and prefrontal cortex.

.

Harris, LT, & Fiske, ST (2006)."Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: Neuroimaging responses to extreme out-groups." Psychological Science, 17(10), 847–853.

This study examines how extreme outgroups (perceived as enemies) are dehumanized, and shows reduced activity in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which is involved in social cognition.

Bruneau, EG, Dufour, N., & Saxe, R. (2012)."Social cognition in members of conflict groups: Behavioral and neural responses in Arabs, Israelis, and South Americans to each other's misfortunes." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 367(1589), 717–730.

This article investigates neural responses to enemy groups in conflict zones, focusing on empathy and perspective taking, using fMRI to analyze brain regions involved in these processes.

Zaki, J., & Ochsner, KN (2012)."The neuroscience of empathy: Progress, pitfalls and promise." Nature Neuroscience, 15(5), 675–680.

This review highlights the brain mechanisms involved in empathy, focusing specifically on the ability to empathize with enemies and how this ability can vary across contexts, involving areas such as the medial prefrontal cortex and the temporal-parietal junction.

Decety, J., & Yoder, KJ (2016)."Empathy and motivation for justice: Cognitive empathy and concern, but not emotional empathy, predict sensitivity to injustice for others." Social Neuroscience, 11(1), 1–14.

This study examines how cognitive and emotional empathy affect responses perceived as stem from adversary’s unfairness, emphasizing brain networks involved in empathy and sensitivity to justice.

These manuscripts provide a basis for understanding how the brain processes the concept of enemies, from threat identification to dehumanization, and how empathy and cognitive control mechanisms can regulate these processes.

The Enemy Theory

The Enemy Theory refers to a broad set of ideas in social psychology, political science, and conflict studies that examine how and why individuals or groups perceive others as enemies. It examines the psychological, sociological, and sometimes evolutionary underpinnings of how people create an "enemy" image and the effects of this perception on behavior and intergroup relations.

Key concepts in the theory of the enemy

In-group dynamics versus out-group dynamics:

A central principle in enemy theory is the idea of ingroup (us) versus outgroup (them). Humans naturally tend to form groups based on shared identity, values and interests. Those who do not belong to the same group or hold opposing views are often classified as outsiders and, in extreme cases, as enemies. This can lead to biases, prejudices and stereotypes.

Psychological mechanisms:

Social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979): This theory suggests that individuals derive part of their identity from the groups to which they belong. Hostility toward outgroups, or "enemy groups," can be a way to improve one's group status or self-esteem.

Scapegoat: Enemy theory is closely related to the concept of scapegoating, where an individual or group is unfairly blamed for wider social problems, often due to frustration or discontent within the group.

Dehumanization: When seeing others as enemies, people tend to dehumanize them, perceive them as less than human, which justifies aggressive or violent actions against them.

Conflict and threat perception:

The enemy perception often arises when one group feels threatened by another group. This can be due to real or imagined threats to security, resources or values. Realistic conflict theory (Sherif, 1966) assumes that intergroup hostility and the perception of the enemy are intensified when groups are in direct competition for limited resources.

Psychological and emotional reactions:

Perceiving someone as an enemy evokes strong emotional responses, such as fear, anger, and mistrust. Neuroscience studies have shown that areas of the brain associated with fear and aggression, such as the amygdala, are activated when people think about or confront their enemies.

Cognitive dissonance: People often experience cognitive dissonance when they are forced to communicate or reconcile with enemies, especially when the enemy's actions challenge existing beliefs or prejudices.

Socio-political meanings:

Leaders and governments throughout history have used the concept of enemies to rally support and justify actions, including warfare. By framing a rival country, ideology, or group as the enemy, they can unite the population against a common threat.

propaganda: The creation of an enemy image is often driven by propaganda, where the media and political actors emphasize or exaggerate threats posed by an outgroup to strengthen group cohesion.

Evolutionary roots:

Some theories suggest that enemy perception has deep evolutionary roots, stemming from early human competition for survival, resources, and mates. The ability to quickly recognize and respond to threats was essential for early human communities, and these psychological mechanisms are present in modern social contexts.

Applications of enemy theory

International relations: In geopolitical conflicts, adversary theory helps explain how countries see each other as threats. The Cold War, for example, was characterized by a perception of mutual enmity between the United States and the Soviet Union, even in the absence of a direct military confrontation.

Social conflict: In social and ethnic conflicts, the enemy theory can explain why groups denigrate and dehumanize others. The Rwandan genocide and other ethnic cleansings are extreme examples of how enemy images can escalate violence.

Psychotherapy and conflict resolution: The enemy theory is also relevant in conflict resolution and peace building efforts. Understanding the cognitive biases and emotional responses that lead to enemy perception can help de-escalate conflicts by promoting empathy, perspective-taking, and dialogue between adversaries.

The role of enemy theory in modern society

In today's world, enemy theory has implications for understanding the psychological dynamics behind polarization, radicalization, and terrorism. In highly polarized political environments, groups may increasingly see their opponents as enemies, leading to social division, hostility and, in some cases, violence.

In conclusion, enemy theory provides a framework for understanding why humans perceive others as threats or adversaries and how this perception affects behavior and social outcomes. She emphasizes the importance of social identity, competition, threat perception and emotional reactions in creating enemy images.

What is enemy system theory?

Enemy system theory is a concept developed in the field of political psychology and the study of conflict, mainly by the psychoanalyst and political theorist Amyk Volken. It explains the psychological and social mechanisms by which groups and nations develop and maintain the perception of the enemy, often as a way to cope with internal anxiety, insecurity, or trauma. The theory is particularly relevant to understanding the persistence of long-standing conflicts and hostilities between groups, nations or ethnic groups.

Amyk Vulcan, American Psychiatrist and Psychoanalyst . He served as a professor of psychiatry in University of Virginia on Charlottesville.

Key concepts in enemy systems theory

Psychological need for the enemy:

According to enemy system theory, groups and nations sometimes develop a collective need for an enemy to manage internal emotional or psychological conflicts. When a society or group experiences collective trauma, frustration, or anxiety, they may externalize these negative feelings by projecting them onto an "enemy." The external enemy becomes a psychological tool to consolidate the group and create a sense of security and identity.

This process often involves projecting inner fears, guilt, or perceived weaknesses onto another group, which is seen as the source of all threats.

Shared group identity:

Vulcan's theory emphasizes that cohesion within the group is often strengthened through the creation of an external enemy. By defining an out-group as dangerous or evil, the in-group solidifies its own identity. This image of a common enemy helps reduce internal disputes, bind group members around common goals, and provide a sense of collective purpose.

This mechanism is evident in political, national and even ethnic conflicts where leaders use the enemy's rhetoric to unite their populations or divert attention from internal issues.

Historical grievances and selected trauma:

A central aspect of enemy system theory is the concept of selected trauma. It refers to a historical event in which a group experienced severe suffering or loss, which then become part of the group's collective memory and identity. The trauma is "chosen" in the sense that it is mentioned, remembered and passed on over and over again from generation to generation, instilling hostility towards the perceived enemy.

Selected glories are also important. These are historical victories or positive memories that a group celebrates and uses to strengthen its identity in contrast to the enemy.

These collective memories of trauma and glory contribute to the perpetuation of enmity, and are often entrenched in the psyche and culture of the group.

Dumping and scapegoating:

Similar to the psychoanalytic concept of projection, in enemy system theory, a group may project its negative traits or internal conflicts onto an external group. In this way, the group avoids dealing with internal problems or insecurity. This outgroup becomes a scapegoat, blamed for the group's troubles and seen as an existential threat.

This psychological process is often intensified in times of crisis, such as economic instability, political turmoil or social change.

Psychosocial defense mechanism:

Creating an enemy is used as a defense mechanism for the group. Just as individuals develop defense mechanisms (such as denial or projection) to cope with anxiety, so too do groups create and maintain enemy images to manage collective anxiety.

By focusing attention on the enemy, the group can distract from internal conflict or unresolved trauma. It helps maintain a sense of security and stability, even though the enemy is often a symbolic or exaggerated threat.

Enmity circles:

Once an enemy system is established, it tends to perpetuate itself in a cycle of hostility. The group's negative feelings toward the enemy provoke defensive or aggressive actions, which in turn lead to counter-hostility on the part of the enemy group. This cycle may escalate over time, leading to entrenched conflicts that are difficult to resolve.

The "us against them" mentality is deeply embedded in both the group's culture and its political discourse, making reconciliation or peace efforts challenging.

Practical Applications of Enemy Systems Theory

International relations and conflict:

Enemy system theory is very relevant to understanding long-term international conflicts, such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Indian-Pakistani conflict or the Cold War. In these cases, images of the enemy have been reinforced for decades, fueled by historical trauma, political leaders and social narratives.

The theory suggests that in order to reach a conflict resolution, the parties must address not only the political and material factors of the conflict but also the psychological and emotional dimensions, especially the collective memories of trauma and the deeply rooted images of the enemy.

Nationalism and populism:

The theory can also explain the rise of nationalism and populism in modern politics. Leaders often use enemy rhetoric to rally their base, portraying outsiders (immigrants, ethnic minorities, or foreign countries) as threats to the nation's identity or security. This strengthens the group's cohesion while diverting attention from internal issues such as economic inequality or political corruption.

Conflict resolution and peace building:

Understanding the enemy system is essential to planning effective peacebuilding interventions. Reconciliation efforts must address not only the tangible aspects of the conflict (such as territory or resources), but also the psychological scars that groups bear. It involves working with collective memories of trauma and fostering a dialogue that humanizes the other side.

Programs build empathy. Those that challenge the images of the enemy and encourage perspective-taking can be effective in breaking the cycle of hostility. Dealing with the psychological need for the enemy is the key to changing long-standing conflicts.

Conclusion

Enemy systems theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how and why groups or nations create and maintain enemy images. He examines the psychological defense mechanisms at work, the role of historical trauma and the emotional functions the enemy serves. By projecting fears, frustrations, and internal conflicts onto an enemy, groups can achieve cohesion and stability, but this often perpetuates cycles of hostility that are difficult to break. Effective conflict resolution, according to this theory, must address both the material and the emotional dimension of the conflict.

Appendix D

Thoughts about the set of Me-representations

The representation of the self, or the "self" group, involves constant monitoring of one's status, needs and goals in a social and physical environment. The brain represents the self as distinct from others through several neural mechanisms:

Temporoparietal Junction (TPJ):The TPJ is involved in distinguishing self from others, especially in terms of agency and ownership. It plays a critical role in physical self-awareness and social discernment, and enables the brain to differentiate one's own actions from those of others.

Insula: The insula helps to represent internal bodily states (introception), and contributes to the subjective experience of being yourself. It is involved in assessing personal physical and emotional well-being, helping to ground the experience of "I" in the visceral feelings.

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC):This area is related to self-control and executive functions. It helps regulate impulses and actions in line with personal goals and values, facilitating a coherent sense of self-agency.

This system integrates body awareness, personal identity, and provides a framework for self-reference and posture for navigating social environments and maintaining self-coherence.

Appendix E

The effect of emotion in the combination and unification of mental components and in the influence on the interpretation of the events of reality

The emotion plays a crucial role in the psychological processes that integrate and unify mental components, and influence the way people perceive, interpret and react to reality events. In our model, a significant emotional impact can in relevant contexts raise or lower a character in the hierarchy of the character board or if it is a strong negative emotion towards a certain character in reality for internalization in the group of enemies. The emotion and its intensity in relation to a certain character are affected both internally by the dynamics in the board and/or in the group of enemies and by the events of the external reality as it is interpreted in the reflective agency. As a rule, the reflective agency has a modulating effect on the intensity of emotion. We note that current Me-representations mainly serve as a kind of container for the flow of emotional, cognitive and behavioral information from the board of internalized characters.

Below we will provide a brief overview about the comprehensive effect of a variety of emotions which has long been recognized as a fundamental element of the human experience, that plays a central role in shaping thoughts, behaviors and perceptions. We will point out that while cognition and emotion were traditionally studied in isolation, contemporary research emphasizes the mutual connection between them in the construction of mental reality. This review emphasizing the importance of emotions will refer to emotions in the context of object relations and attachment theories.

Historically, emotions and cognition were seen as separate entities, where cognitive processes were considered the main causes of behavior and influence of the feelings was seen as a secondary and disruptive effect. However, this dichotomy has been increasingly challenged, leading to a more integrated understanding of the interrelationships between emotions and cognition. The works of philosophers such as William James and psychologists such as Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung emphasized the fundamental role of emotions in shaping conscious and unconscious thought processes.

Modern theories suggest that emotional states are not just appendages to cognitive processes, but are deeply embedded in the mental framework that guides perception, memory and decision-making. Theories such as the infusion model of the emotion – (Affect Infusion Model) Forgas, 1995) and the somatic marker hypothesis (Somatic Marker Hypothesis – Damasio, 1994) suggest that the emotion serves as an agent necessary and essential which combines various cognitive and sensory inputs, and creates coherent and unified mental experience.

The effect of emotion is therefore a unifying force connecting different mental components, such as thoughts, memories and sensory perceptions, into a cohesive whole. This unification is possible through several mechanisms:

Emotional labeling: Emotional states provide emotional tags to cognitive representations, improving their salience and accessibility. For example, emotionally charged memories are more likely to be recalled and influence subsequent interpretations of events.

Emotional modulation: Affects cognitive processes such as attention, perception and memory consolidation. Positive emotional effect tends to expand the cognitive canvas, facilitate creative thinking, while influencing emotional negativity narrows the focus, and improves analytical processing.

Neuroscience research has identified several brain regions involved in the integration of emotional and cognitive information. The prefrontal cortex, particularly the medial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), plays a critical role in integrating emotional and cognitive signals to guide decision-making and social behavior. The amygdala, traditionally associated with processing fear and other negative emotions, is now seen to be involved in attributing emotional meaning to a wide variety of stimuli, thus influencing cognitive interpretations.

Emotion shapes the interpretation of reality by affecting how people perceive and evaluate events. This process is mediated by several routes:

Matching the mood: People are more likely to perceive and interpret events in ways that match their current emotional state. For example, a person in a happy mood may interpret ambiguous social cues as friendly, while a person in a sad mood may perceive the same cues as hostile.

Emotional regulation and reappraisal: Emotional regulation strategies, such as cognitive reappraisal, involve reinterpreting events to change their emotional impact. Emotional states can ease on-or hinder the effectiveness of these strategies, thus shaping the constructed reality of the individual.

Emotional biases and distortions: Emotion can also present biases in the interpretation of reality, which leads to distortions that may contri bute to psychopathology. For example, people with anxiety disorders may exhibit heightened sensitivity to stimuli associated with threat, interpreting benign events as dangerous. Conversely, emotional flattening in depression may cause a decrease in the ability to derive pleasure from positive events, which contributes to a pessimistic world view.

To understand the role of influence of a combination of mental components on the interpretation of reality has significant implications for clinical practice. Therapeutic approaches such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and psychodynamic therapy can benefit from addressing the interrelationships between emotional and cognitive processes. Techniques aimed at increasing awareness and emotional regulation can promote a healthier integration of mental components and foster more adaptive interpretations of reality.

Emotion therefore can be seen as a central organizing force in the psyche, which plays a critical role in combining mental components and shaping the interpretation of reality events. Emotion not only unifies the mental landscape but also serves as a lens through which people build their experiential world.

References

Damasio, AR (1994). Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Putnam Publishing.

Forgas, JP (1995). Mood and judgment: The Affect Infusion Model (AIM). Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 39-66.

James, W. (1884). What is an emotion? Mind, 9(34), 188-205.

Freud, S. (1915). The unconscious. In Collected Papers (Vol. 4, pp. 98-136). Hogarth Press.

Having said the above, the question arises what the role of the emotion in internalizing human figures from the birth to later stages of life?

The effect of the emotion, which encompasses a variety of emotional experiences, significantly affects the internalization of human characters throughout life. From early attachment experiences with primary caregivers to complex social relationships in adulthood, emotional interactions shape internalized representations of others, called "object representations" in psychoanalytic theory. We have criticism for calling the internalized characters "objects". First, objects refer to a huge set of objects and why call figures as objects. Secondly, did these psychoanalysts seek to equate their thoughts and writings with a dimension of objectivity by naming characters as objects. Thirdly, and in our opinion, there is something inhumane in this expression in which characters are called objects. But that's our reservations. And hence we will still use this nickname.

The process of internalization, in which external human figures are integrated into the psyche as internal objects or representations, is fundamental to psychological development and functioning. the effect of the emotion plays a central role in this process, and provides the emotional context that shapes the way these figures are perceived, interpreted and stored in the mind. From birth, infants engage in emotional exchanges with their caregivers, which lay the foundation for the internalization of human figures.

Classical psychoanalytic theory, as proposed by Freud and later expanded by object relations theorists such as Melanie Klein and Donald Winnicott, emphasizes the importance of early relationships in the development of internal objects [internalized characters in other words]. These internal objects, shaped by emotional experiences, influence the individual's capacity for relationships, self-regulation, and identity formation. The quality of these internalized figures, whether nurturing or punishing, depends largely on the emotional tone of early relational experiences.

Attachment theory, introduced by John Bowlby and developed by Mary Ainsworth, provides a solid framework for understanding the role of emotions in the internalization process. The communication system is activated in times of distress, when the caregiver’s responds determine the baby's sense of security. Secure attachment is characterized by consistent, warm and responsive care, leading to the internalization of a character on a "safe base". Conversely, inconsistent or neglectful treatment may result in anxious or avoidant attachment patterns, which reflect less adaptive internalized figures.

From birth, infants are immersed in an emotional environment, with their primary caregivers serving as the primary source of emotional regulation and reassurance. Through processes such as mirroring and attunement, caregivers reflect on the infant's emotional states, and help the child identify and organize its emotional experiences. These mutual exchanges of feelings are essential for the formation of the main caregiver as an internalized figure.

Mirroring and tuning: Caregivers who accurately reflect the baby's emotional state enable the development of a coherent self and a safe and internalized representation of the caregiver. Conversely, lack of adjustment can lead to fragmented Me-representations and an insecure internal object.

Emotional bride: the caregiver's ability in containing and soothing the baby's disturbing feelings helps the child internalize a figure that is seen as reliable and able to provide comfort. This process contributes to the development of basic trust and confidence.

Object’s constancy ,i.e the ability to maintain an internalized representation of a caregiver despite his physical absence appears in early childhood. Emotional stability in the caregiver’s relationship is essential for this developmental milestone. Disruptions in the caregiver's availability or emotional responsiveness may lead to difficulties in developing object constancy, resulting in unstable and fragmented internalized figures.

As children grow, their internalized characters become more and more complex, reflecting a wider range of emotional experiences. Relationships with peers, teachers and other significant figures contribute to the formation and diversification of internal objects.

Peer relationships: Emotional interactions with peers allow correction and expansion of internalized figures beyond the primary caregiver. Positive peer relationships can moderate earlier deficits, while negative experiences can reinforce maladaptive internal representations.

Adolescent rebellion and emotional reappraisal: During adolescence, the process of individuation often involves a reevaluation of parental figures. Emotional conflicts with parents may lead to a change or rejection of previously internalized figures, as the adolescent strives to create a separate identity.

Adolescents continue to develop regulatory emotional capacity, which is influenced by the quality of their internalized characters. The ability to calm and manage emotional distress is related to the internalization of figures perceived as supportive and emotionally available. Conversely, critical or rejecting internalized figures can contribute to dysregulated affect and maladaptive coping strategies.

Maturity provides opportunities to change and reshape internalized characters through new relational experiences. Romantic relationships, friendships, and professional interactions can all influence internalized representations of Me and others.

Romantic relationships: Emotionally significant romantic relationships can evoke and change early internalized characters. A partner who provides a corrective emotional experience may help change internalized representations of the others, which will lead to healthier relational patterns.

Therapeutic relationships: Psychotherapy offers a unique context in which internalized characters can be explored and changed. The therapist, through a consistent and emotionally oriented presence, can serve as a new internal object, facilitating the correction of maladaptive internalized characters.

Even later in life, the process of internalizing new human characters continues, which is influenced by emotional experiences such as losses, new relationships and personal achievements. The flexibility of internalized characters depends on the individual's ability to affect regulation and openness to new emotional experiences.

Understanding the role of emotions in internalizing human figures has significant implications for therapeutic practice. Therapists can facilitate the correction of maladaptive internalizations by providing a consistent, directed, and accepting presence. Techniques that improve awareness and emotional regulation can help clients integrate new and healthier internalized characters, and promote psychological well-being.

Hence emotional component is basic in internalizing human figures, it has a profound influence on the design, formation and correction of internal representations from birth to later stages of life. Emotional context in which internalization occurs determines in many ways the quality and stability of internalized figures, and influences relationship patterns and psychological functioning.

References

Bowlby, J. (1988). A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. Basic Books.

Klein, M. (1952) Some Theoretical Conclusions regarding the Emotional Life of the Infant. In: The Writings of Melanie Klein, Volume 8: Envy and Gratitude and Other Works, Hogarth Press, London, 61-94.

Winnicott, DW (1965). The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment. International Universities Press.

Stern, DN (1985). The Interpersonal World of the Infant. Basic Books.

That's it for now

your

Dr. Igor Salganik and Prof. Joseph Levine

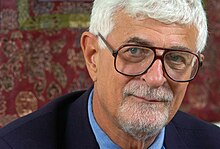

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Leave a comment