Conversation 60: Stockholm syndrome in the perspective of the directorate of internalized figures

Greetings to our readers,

Stockholm syndrome describes the psychological state of the victim who identifies with the captor or abuser and their goals. Stockholm syndrome is relatively rare; A report by the FBI, the American estimates that the situation occurs in about 8% of hostage victims.

The name of the syndrome is derived from a failed bank robbery in Stockholm, Sweden. In August 1973, four Sveriges Kreditbanken employees were held hostage in the bank's vault for six days. During the confrontation, an apparently inappropriate relationship developed between the captive and her captor. One of the female hostages, during a telephone conversation with Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, even said that she completely trusts her captors, but fears that she will die in a police attack on the building.

Below is a breakdown of the course of events at the bank from the article at https://www.history.com/news/stockholm-syndrome

On the morning of August 23, 1973, an escaped prisoner crossed the streets of Sweden's capital and entered a bustling bank, Sveriges Kreditbanken, in Stockholm's prestigious Norrmalmstorg Square. Under his jacket was an extendable object that he carried in his arms, upon entering the bank Jan-Erik Olsson pulled out a loaded submachine gun, fired at the ceiling, and disguising his voice to sound like an American, shouted in English, "The party has just begun!"

After wounding a police officer who responded to a silent alarm, the robber took four of the bank's employees hostage. It was Olsson, a safecracker who did not return to prison after a vacation during his three-year sentence for major fraud. Olsson demanded more than $700,000 in Swedish and foreign currency, a getaway car and the release of Clark Olofsson, who was serving a prison sentence for robbery and was an accomplice in the 1966 murder of a police officer.

Within hours, the police paid the ransom and even brought a blue Ford Mustang with a full tank of gas. Clark Olofsson was also released and joined Jan Olsson. However, authorities refused the robber's demand to leave with the hostages to ensure safe passage.

The unfolding drama grabbed headlines around the world and played out on TV screens across Sweden. The public flooded the police headquarters with proposals to end the conflict, which ranged from a concert of religious tunes by the Salvation Army band to sending a swarm of angry bees to sting the criminals until they surrender.

At Olsson’s command, the kidnapped locked themselves in a crowded bank safe, and soon formed a "strange" relationship with their captors. Olsson draped a woolen coat over hostage Kristin Enmark's shoulders when she began to shake, soothed her when she had a bad dream and gave her a bullet from his pistol as a souvenir. The shooter comforted the captive Birgitta Lundblad when she was unable to make contact with her family by phone and told her: "Try again; don't give up."

When hostage Elizabeth Oldgren complained of claustrophobia, he allowed her to leave the vault attached to a 100-foot rope, and Oldgren told a New Yorker reporter a year later that even though she was strapped in, "I remember very well that I thought it was very kind of him to let me leave the vault."

Olson's benevolent actions aroused the sympathy of the hostages. "When he treated us well," said hostage Sven Sepstrom, "we could think of him as a god who appeared to us in an emergency."

On the second day, the hostages were already talking privately with their captor, and they began to fear the police more than their captors. When the commissioner was allowed inside to check on the health of the hostages, he noticed that the captives seemed hostile towards him but calm and cheerful with the gunmen.

The police chief told the press that he doubted that the gunman would harm the hostages because they had developed "a fairly relaxed relationship ".

Enmark even called Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, who was already busy with the upcoming general election and a deathbed vigil for the revered King Gustav VI Adolf, 90, and begged him to let the robbers take her with them in the getaway car.

"I completely trust Clark and the robber," she assured Palma. "I'm not desperate. They didn't do anything to us. On the contrary, they were very nice. But, you know, Olof, what I'm afraid of is that the police will attack and make us die."

Even when they were threatened with physical harm, the hostages still saw compassion in their captors. After Olsson threatened to shoot Sven Säfström in the leg to shock the police, the hostage told The New Yorker: "How well I thought he said it was just my leg that he was going to shoot." Enmark tried to convince her friend the hostage to "accept" the bullet: "But Sven, it's only by foot."

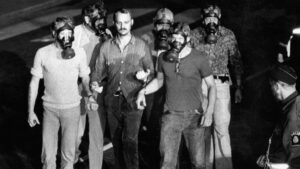

In the end, the kidnappers did not physically harm the hostages, and on the night of August 28, after more than 130 hours, the police poured tear gas into the safe and the attackers quickly surrendered. The police called for the hostages to leave first, but the four captives, who defended their captors to the end, refused. Enmark yelled, "No, Jan Olsson and Clark Olofsson go first – you'll shoot them if we go first!"

Police officers in gas masks escort 32-year-old Jan Erik Olsson from the bank.

At the door of the vault, the prisoners and the hostages hugged, kissed and shook hands. When the police caught the two gunmen, two female hostages shouted: "Don't hurt them – they didn't hurt us." As Enmark was carried away on a stretcher, she shouted to the handcuffed Olofsson, "Clark, I'll see you again."

The seemingly irrational connection of the hostages to their captors confused the public and the police, who even investigated whether Enmark had planned the robbery with Olofsson. The captives were also confused. A day after her release, Oldgren asked a psychiatrist: "Is there something wrong with me? Why don't I hate them?"

Psychiatrists compared the behavior to the battle shock displayed by the soldiers during the war, and explained that the hostages were emotionally indebted to their captors, and not to the police, for saving them from death. A few months after the failed robbery, psychiatrists called the strange phenomenon "Stockholm syndrome".

Even after Olofsson and Olsson returned to prison, the hostages paid visits to their former captors. An appeals court overturned Olofsson's conviction, but Olsson spent years behind bars before being released in 1980. After he was released, he married one of the many women who sent him letters of admiration while he was imprisoned, moved to Thailand and in 2009 published his autobiography, called "The Stockholm Syndrome".

The most well-known example of Stockholm Syndrome is the one involving the kidnapped newspaper heiress Patricia Hearst. In 1974, about 10 weeks after being taken hostage by the Symbionese Liberation Army, Hearst helped her captors rob a bank in California.

Patricia was finally caught by authorities in San Francisco on September 18, 1975, and was charged with bank robbery and other crimes. Her trial was as sensational as her pursuit. Despite the allegations of brainwashing, the jury found her guilty, and she was sentenced to seven years in prison. Hearst served two years before President Carter commuted her sentence. She was later pardoned.

[https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/patty-hearst]

But it was during the Iran hostage crisis (1979-81) that Stockholm syndrome worked its way into the public imagination.

The syndrome was also mentioned after the hijacking of TWA Flight 847 in 1985. Thus, on June 14, 1985, TWA Flight 847 was hijacked by Muhammad Ali Hammadi and a second terrorist brandishing grenades and guns during a routine flight from Athens to Rome. For 17 harrowing days, TWA airline pilot John Testarka was forced to cross the Mediterranean Sea with his 153 passengers and crew, from Beirut to Algiers and back, landing in Beirut three times before he was finally allowed to stop. The terrorists tied up passengers, beat them and threatened to kill them if hundreds of Lebanese were not released from Israeli prison. See:

[https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/hijacking-of-twa-flight-847]

Although the passengers endured an ordeal of hostages that lasted more than two weeks, upon their release some expressed open sympathy for the demands of their captors.

Another example is Westerners kidnapped by Islamist militants in Lebanon. Hostages Terry Anderson (1985-91), Terry White (1987-91) and Thomas Sutherland (1985-91) all claimed that they were treated well by their captors, despite the fact that they were often held in solitary confinement and chained in small, filthy cells.

Similar reactions were presented by the hostages held in the Japanese embassy in Peru in 1996-97.

It is not fully understood why Stockholm syndrome happens. Some researchers suggest that this is a survival mechanism in which further harm is reduced by the victim showing obedience and gratitude. Another theory states that the victim's gratitude is created after the abuser or captor perpetuates the fear [for example of a bank robber threatening to shoot the victim to death] without actually harming the victim.

Other psychologists who have studied the syndrome believe that the bond is initially formed when a captor threatens a captive's life, hesitates, and then chooses not to kill the captive. The prisoner's relief at the removal of the threat of death turns into feelings of gratitude towards the captive for giving his life.

As the incident of the bank robbery in Stockholm proves, it only takes a few days for this relationship to be established, and proves that already at an early stage, the victim's desire to survive outweighs the urge to hate the person who created the situation.

The survival instinct is at the heart of Stockholm Syndrome. The victims live in forced dependence and interpret rare or small acts of kindness in the midst of terrible conditions as good treatment. They often become hypervigilant to the needs and demands of their captors, making psychological connections between their captors' happiness and their own.

Indeed, the syndrome is characterized not only by a positive relationship between the captive and the captive, but also by a negative relationship on the part of the captive towards the authorities that threaten the captive-captor relationship. The negative attitude is particularly strong when the hostage does not benefit the returnees but as leverage against a third party, as often happened with political hostages.

In the 21st century, psychologists have extended their understanding of Stockholm syndrome to hostages in other groups, including victims of domestic violence, cult members, prisoners of war, abused children, and more. We note that the American Psychiatric Association does not yet include Stockholm syndrome in the manual DSM-5 [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5], possibly in light of the existence of limited empirical research that verifies the existence of Stockholm syndrome as a psychiatric diagnosis. See:

[Arpita Kakkar & Alisha Juneja. Psychology in pathology: Stockholm syndrome

Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (Apr. 19, 2024).]

Stockholm syndrome: an AI-assisted illustration

Interestingly, an article appeared in 2023 titled "Reconciliation: Replacing the Stockholm Syndrome with the Definition of a Survival Strategy".

[Bailey, R., Dugard, J., Smith, S. F., & Porges, S. W. (2023). Appeasement: replacing Stockholm syndrome as a definition of a survival strategy. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(1), Article 217233]

This thought-provoking article examines the concept of Stockholm syndrome and proposes a new term, "reconciliation", anchored in poly-vagal theory [see below]. The authors argue that this new term better captures the complex emotional dynamics between trauma survivors and their perpetrators, especially in life-threatening situations.

The article presents several key arguments regarding the concept of "reconciliation" as a survival strategy, replacing the traditional concept of Stockholm syndrome:

Definition and context: The authors claim that "reconciliation" more accurately describes the adaptation strategies used by survivors in life-threatening situations, emphasizing the asymmetry in the relationship between the victim and the attacker. Unlike Stockholm syndrome, which implies mutuality, reconciliation focuses on the survivor's instinctive response to regulate and calm the captor in order to minimize harm.

Neurobiological Mechanisms: The article highlights the role of the autonomic nervous system in shaping the responses of both survivors and aggressors. It assumes that the survivor's ability to maintain a regulated state of mind and homeostasis can affect the criminal's nervous system, which may lead to a reduction in violence. This interaction is framed in the context of the poly-vagal physiological theory, which explains how physiological states can influence social behavior and emotional responses.

Survival strategy: The authors suggest that reconciliation is a powerful, unconscious survival response that can emerge in situations of interpersonal violence. They claim that this response is not only a learned behavior but an instinctive strategy that can improve the chances of survival in the face of life threats.

Normalizing survivor experiences: By framing reconciliation as a legitimate survival mechanism, the authors aim to de-stigmatize survivors' behaviors, and provide a science-based explanation for their otherwise misunderstood actions. This perspective encourages a more compassionate understanding of the complexity of trauma responses

Research Implications: The article calls for further research to examine how recognizing reconciliation as a factor of resilience can positively impact the recovery process of survivors. It emphasizes the need to conceptualize the survivors' experiences from their point of view and not from the perpetrator's point of view. In general, the article supports a shift in understanding trauma responses, emphasizing the adaptive nature of reconciliation in the context of survival.

We will expand a little from the article on the poly-vagal theory, developed by Steven Forges.

[Poly-vagal theory (PVT) is a collection of proposed evolutionary, neuroscientific, and psychological constructs concerning the role of the hypothalamus in emotional regulation, social bonding, and fear response. The theory was presented in 1994 by Steven Forges.

Stephen Forges – Professor of Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

This theory plays a crucial role in the proposed definition of reconciliation in the article. Here are the main points of this relationship:

Regulation of the autonomic nervous system: the poly-vagal theory [related as mentioned to the vagus nerve] assumes that the autonomic nervous system has different pathways that influence emotional and social behaviors. The theory identifies three main states: the ventral vagal state (related to safety and social engagement), the sympathetic state (related to the Fight or Flight state), and the dorsal vagal state (related to shutting down or silencing). The article suggests that reconciliation involves navigating between these situations in order to maintain a regulated nervous system and a state of homeostasis if possible, which can also affect the state of the offender.

Co-regulation: The idea of co-regulation is central to both poly-vagal theory and the idea of reconciliation. The article argues that when survivors can approach a situation in a calm and emotionally regulated state, they can project cues of reassurance that may help calm the perpetrator's nervous system. This two-way interaction is seen as a survival strategy, where the survivor's ability to project such a social attitude can potentially diffuse aggression and reduce the risk of harm.

Survival mechanism: The authors suggest that reconciliation is an instinctive survival mechanism that can appear in response to life-threatening situations. Poly-vagal theory supports this by explaining how the nervous system prioritizes safety and soothing social connections, which can be critical in high-stress environments. The ability to engage in reconciliation reflects a sophisticated neural ability to balance the need for social connection with the willingness to respond to threats.

Understanding survivors' behavior: By applying poly-vagal theory to the concept of reconciliation, the authors hope to provide a more complex understanding of survivors' behavior. They argued that recognizing the neurobiological underpinnings of these responses could help normalize and validate the experiences of survivors, and move away from the stigmatizing implications of Stockholm syndrome.

In summary, poly-vagal theory substantiates the concept of reconciliation by explaining the physiological and psychological mechanisms that enable survivors to navigate life-threatening situations through social engagement and co-regulation, ultimately increasing their chances of survival.

By the way, as discussed earlier, this article also notes that the term "Stockholm syndrome" is commonly used in contexts involving hostage situations, abusive relationships, and other scenarios where there is a significant power imbalance between victim and perpetrator. The article describes a phenomenon in which victims develop a bond or sympathetic feelings toward their captors, which often leads to behaviors that appear to support or protect the attacker. The article notes that this term has been applied in various situations, including:

Kidnapping: The victims may show loyalty or affection towards their captors, and sometimes refuse to cooperate with law enforcement authorities or express understanding for the kidnapper's actions.

Intimate Partner Violence: Survivors may develop emotional attachments to their abuser, which can complicate their ability to leave the relationship.

Human Trafficking: Victims may form relationships with their traffickers, which can hinder their escape and recovery efforts.

Hostage situations: In these scenarios, victims may show signs of empathy or connection with their captors, which can be mistaken for a positive relationship.

The article criticizes the concept of Stockholm syndrome for several reasons:

Misinterpretation of relationships: The authors argue that Stockholm syndrome implies a mutual bond or affection between the victim and the perpetrator, which does not accurately reflect the dynamics of kidnapping or abuse. They emphasize that the relationship is not symmetrical, with the victim's survival often dependent on reconciliation rather than a genuine emotional connection.

Lack of empirical support: The article indicates that there is limited empirical research that verifies the existence of Stockholm syndrome as a psychiatric diagnosis. The concept is largely derived from media descriptions rather than scientific evidence, which raises questions about its validity and relevance in understanding survivors' experiences.

Focusing on the perspective of the perpetrator: Stockholm syndrome is criticized for being framed from the perspective of the perpetrator or an outside observer, which can ignore the complexity of the survivor's experience. The article calls for changing the focus to the perspective of the survivor, emphasizing his instinctive reactions to life-threatening situations.

Oversimplification of trauma responses: The authors argue that the term oversimplifies the range of psychological and physiological responses that survivors may display. By framing these responses as a form of bonding, he fails to acknowledge the adaptive strategies, such as reconciliation, that survivors may use to navigate their life circumstances.

In conclusion, while Stockholm syndrome is widely used to describe certain behaviors of survivors, the article suggests that it fails to capture the complexity of trauma responses and power dynamics in abusive situations. The authors suggest replacing it with the term "reconciliation" to better reflect the survival strategies of the victims.

What do you think, the reader, what is your opinion about it?

We will now move on to our model for understanding the "self".

The model includes the "primary self" and the "secondary self":

We will first refer to the primary self (Biological Predestined Core): the primary self consists of innate biological structures and instincts that form the innate basis of personality and cognitive processes. This self has its own dynamics during a person's life and is subject to changes with age, following diseases, traumas, drug consumption, addiction, etc. Within the primary self there is the potential for instrumental abilities that are innate, but they can also be promoted, or on the contrary suppressed through the influence of the reference groups.

The primary self also has cognitive abilities that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment during the first years of life. In addition, the primary self includes the temperament and emotional intelligence that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment in the first years of life. And finally, it includes an energy charge that is mostly innate but can be suppressed through the influence of reference groups, as well as through situational factors.

The primary self also includes the six Individual Sensitivity Channels (ISC): sensitivity channels that are individual in their strength and impact and reflect the individual's reactivity to stressors (both external and internal). So far we have identified six channels of sensitivity:

1] Sensitivity regarding a person's status and location (the Status Channel)

2] Sensitivity to changes in norms (Norms Channel)

3] Sensitivity in relation to emotional attachment to others (the Attachment Channel)

4] Threat sensitivity (Threat Channel)

5] Sensitivity to routine changes (Routine Channel)

6] Sensitivity to a drop in the energy level and the ability to act derived from it (the Energy Channel).

(See previous conversations for further details).

From the primary self, a superstructure or "secondary self" is developed through the interaction first of the baby and then of the person during his life with the figures around him, which is the basis of the "social self" of the individual consisting of the internalization of influential figures in his life, arranged in a hierarchical order [we called the group of these internalizations metaphorically “Directorate of the internalized characters” or the “Board of the internalized characters”] and there is a continuous dialogue between them and sometimes even conflicts.

When one or more internalized characters have the greatest influence on the attitudes, feelings and behavior of the individual, we call them "the leader-selves" [a figure formerly also called the "dictator-self", see previous conversations]. This leader or leaders can also impose a certain censorship about what will enter or be expressed in the interrelationships in the board of introverted characters.

We note that the events and characters in the external world maintain a kind of dialogue with the internalized characters and may affect the expression and sometimes even the hierarchy of the characters in the board of intrernalized characters.

In addition, it is possible that, similar to short-term memory, parts of which are transferred to long-term memory, also when it comes to the internalization of characters, there is a short-term internalization that, depending on the circumstances, the importance and duration of the character's influence, will eventually be transferred to a long-term internalization in the set of internalized characters.

Below is the structure of the [secondary] social self: This social self consists of "secondary selves" which include the following types:

[1] The variety of "representations of the self" that originate from attitudes and feelings towards the self and its representations in different periods of life. These also include a reflective "representation of the self" that has a certain and rather limited ability to observe the actions of behavior and the mental life of the person [probably also on the representation of the reflective secondary self there is a certain censorship of the leaders of the internalized board in the context of what the person will be aware of or not.]

[2] Representations of internalized characters that originate from the significant characters that the person was exposed to during his life, but as mentioned, there may also be imaginary characters represented in books, movies, etc. that greatly influenced the person.

[3] internalized representations of "subculture" [subculture refers to social influences in the environment in which a person lives and are not necessarily related to a specific person]. We note that the individual is not aware that his actions, feelings and attitudes are caused by the dynamic relationships between these structured characters.

We will add that internalized key figures [usually human], usually refer to the significant people in a person's life who played central roles in shaping his beliefs, values and self-concept. Sometimes, these will also include historical, literary and other figures that left a noticeable mark on the person and were internalized by him.

AI-assisted illustration demonstrating the board of internalized characters, the size of the characters reflects the inner hierarchy The large figure in the center of the head reflects the inner leader (leader-self)

The term "internalized" implies that the influence of these key figures has been absorbed and integrated into the individual's thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors. This internalization occurs through the process of observing, interacting with, and learning from these important people. As a result, the individual may adopt certain values, perspectives, and approaches to life that reflect those of the influential figures.

In addition to the board of characters, the social self also contains the "enemy group" and more precisely the "internalized enemy group" This is the place where the characters that threaten the person are internalized while the dominant characters in the board of characters prevent them from entering and being internalized in the board of characters [we assumed the existence of this group in the last year while thinking about the evolutionary need for the higher animals and for man to create such a group for their survival].

The characters in the "enemy group" are characters with a negative emotional value and are represented in a more schematic way relative to the characters in the board of internalized characters.

We note that usually the transition between the group of the board of directors and the group of enemies is not common and usually happens following the traumatic or threatening event for a person. [See conversation 59 for more details about this group and its development].

We note that the Reference Group Focused Therapy (RGFT) treatment method was developed on this theoretical basis. See about this method in detail in previous conversations.

We will now try to understand the Stockholm syndrome or reconciliation syndrome in the light of the model for the mental system we are developing:

First, it seems that the theoretical model in question can offer an understanding of Stockholm syndrome through two central concepts: the "primary self" and the "secondary self". We will examine how each of these mechanisms affects the onset of Stockholm syndrome.

Primary Self (Biological Predestined Core)

The primary self is, as mentioned, the innate basis of the personality, consisting of biological structures and innate instincts. It includes a variety of instinctive responses designed to ensure survival, such as responses to fear, the need for attachment and security, and more. The primary self is also influenced by initial and early experiences with the environment, such as experiences of trauma or abuse, which may shape the individual's ways of responding to stressful situations. In this self there are as mentioned six channels of sensitivity.

Below is a reference to them in the context of Stockholm syndrome.

The Attachment Channel:

The attachment mechanism is one of the basic components of the primary self. In situations of stress or danger, a person may develop an attachment reaction to a figure that represents the source of the danger, as a way to reduce the risk and ensure survival. Thus in Stockholm syndrome, the victim may develop an emotional bond with the abductor as a way of dealing with fear and uncertainty. The kidnapper, as someone who controls the situation, becomes a key figure with whom the victim seeks to adapt and get along.

If we go into more detail, individuals with sensitivity in the attachment channel may be more likely to develop the syndrome. This can be understood by the fact that such a person needs a relationship and not just a relationship, but a positive relationship that nourishes and supports, and therefore in such a situation he longs for a relationship with the kidnapper who gradually becomes a very dominant figure for him, at first maybe in the group of enemies but because the thing is mentally unbearable for him, the captor or the abuser moves to the board group as a dominant figure who may even rise in the hierarchy over the previous intermalized leader-self. As we have seen, this happens within a day or more [see the case of the robbery in Stockholm in 1973].

The threat channel refers to the individual's ability to identify and respond to threats in his environment. In Stockholm Syndrome, the victim may see any positive response from the kidnapper (such as showing compassion or satisfying basic needs) as a way to reduce the threat. This may lead to the formation of positive feelings towards the abductor, in response to the perceived relief.

It is possible that those who are sensitive in this channel will be more inclined to develop the syndrome or that the abductor's transition from the group of enemies to the directorate of internalized characters will occur faster for them.

This channel refers to the individual's sensitivity to his status and social position in a given environment. In Stockholm Syndrome, a change in the victim's status from someone who is in a free society to someone who is under the control of a captor, leads to adaptation to the needs and expectations of the captor. The victim may try to curry favor with the kidnapper to improve his new and limited status. Here too, it is possible that those who are sensitive in this channel will be more inclined to develop the syndrome or that the abductor's transition from the group of enemies to the directorate of internalized characters will happen faster for them.

The secondary self (or social self) is the structure created in the process of development through interactions with significant figures in the environment. It includes internalizations of figures and other social symbols that the person encounters during his life. The secondary self represents the social side of the personality and includes both the board of directors of the internalized characters, who conduct an internal dialogue and sometimes conflicts among themselves, and the group of enemies.

Representations of internalized figures:

As mentioned, representations of internalized figures are internal representations of significant figures in a person's life, such as parents, teachers, or other authority figures.

In the Stockholm Syndrome, although initially the kidnapper is included in our hypothesis as an emerging figure within the enemy group, but over time [a day or so] the internalized characters in the board can begin to include the kidnapper within his directorate of internalized characters, especially when the victim is under a significant survival threat and tries to understand and explain to himself the behavior of the kidnapper and the general situation. In such cases, the abductor may be perceived as an authority figure with power and control, leading to the internalization of this figure as part of the victim's internal board of directors. It is even possible that due to the intense need to survive in the face of a very threatening situation, the figure of the kidnapper will often receive the status of an internal leader (leader-self).

Dialogue with internalized characters:

As mentioned, the internal dialogue between the internalized figures within the board of directors is dynamic and changes according to new experiences. The victim may develop an internal dialogue in which he begins to see the abductor not only as a threat but also as a figure who can provide protection or "small favors". It is a psychological defense mechanism that allows the victim to feel a certain security in a situation of lack of control. The internal conflicts between the internalized characters can lead to a change in perception and feeling towards the kidnapper, such as a transition from seeing him as an "enemy" to a character with emotional complexity.

Internalizing the enemies:

The “internalized enemy group” is a concept that refers to the internalization of figures that are perceived as threatening to the individual. These figures are characterized by a negative emotional value, they are seen in a more inclusive and schematic way than those in the board of directors group and of course are seen as threatening the well-being of the individual.

In Stockholm Syndrome, the abductor characters probably start their journey usually in the enemy group, but following a complex psychological process that includes defense mechanisms, these characters may begin to move into the internalized character structure. Such a transition is usually relatively rare in normal life cycles, but in cases of Stockholm syndrome, the traumatic events with the threat of survival to life can lead to such a transition.

The internalization of the abductor as part of the internal characters can provide the victim with a sense of control, understanding or even emotional connection. We note that it cannot be ruled out that a certain representation of the kidnapper will still be found in the enemy group despite the transition [see blog 59 regarding such a possibility].

Stockholm syndrome and self-development:

The proposed model emphasizes how Stockholm syndrome is not only an instinctive reaction of the primary self, but also the result of complex internalization processes of the secondary self. The meeting between the basic survival instincts and the internal dynamics of the internalized board and the conflicts between the internalized characters within it, and the relations between the board and the group of enemies, can perhaps explain the emergence of positive feelings towards the kidnappers.

These processes make it possible to understand the development of Stockholm syndrome as a mental survival mechanism that tries to stabilize the victim's mental system in extreme situations.

This understanding also offers an innovative therapeutic direction that focuses on dismantling the internal dynamics and rebuilding them, using models such as RGFT (Reference Group Focused Therapy) designed to address these dynamics and the internal conflicts they create.

Below are several stages and therapeutic processes that can be taken into account:

Identifying and understanding the internalized characters

Mapping the internal directory: the beginning of the treatment will focus on identifying the internalized characters who conduct an internal dialogue within the patient's internal directorate. This includes identifying the figures that represent the kidnappers, other authority figures, or other significant figures.

Understanding the internal hierarchy: understanding the status of each character within the internal board, and the way these characters affect the patient's attitudes, feelings, and behaviors.

Processing and separation between the characters of the "kidnapper" and other characters

Emotional processing: working with the patient on processing the feelings towards the internalized figures related to the kidnappers. This may include understanding the internal conflicts arising from mixed feelings towards the abductors (such as fear, admiration, affection, etc.).

Creating a separation between the "enemy" figures and other figures: encouraging the patient to distinguish between the internalized figures that represent the kidnappers and other figures in the inner board. This separation will allow the patient to recognize that the abductors are not part of the authoritative or parental figures in his life.

Strengthening the reflective self and inner awareness:

Development of the reflective "representation of the self": work on strengthening the patient's ability to observe his behavior, thoughts and feelings from a conscious and reflective perspective. The reflective self can act as a kind of "mediator" between the internalized characters and reduce the dominance of the characters associated with the kidnappers.

Encouraging awareness of the internal conflicts: creating awareness of the internal dialogues and conflicts between the internalized characters, and in particular with those who represent the kidnappers and the victims.

Working with the Indiviadual Sensitivity Channels (ISC)

Identifying the active sensitivity channels: understanding which individual sensitivity channels (such as the attachment channel, the threat channel, the status channel) operate in a dominant way in the patient, and how they may contribute to the formation of Stockholm syndrome.

Handling the channels of sensitivity: developing strategies to manage reactions in these channels. For example, strengthening the strategies that enable communication and getting closer to safer characters, processing threatening experiences and communicating in a healthier way.

Strengthening personal and social forces

Encouraging safe social support: work on developing and expanding the patient's social support network, especially around figures he trusts and who are not perceived as threatening.

Restoring the sense of control and self-authority: strengthening the patient's sense of competence and self-control, with the aim of reducing the dependence of his soul on the kidnappers as authoritative or protective figures.

Work on processing the trauma and restoring identity

Trauma processing: (Focused trauma therapy (such as EMDR or prolonged exposure therapy) to process the traumatic experiences and change the automatic reactions resulting from them.

Identity reconstruction: work on building a renewed identity that does not depend on the innate reactions or internalized characters associated with the abductors. This may include exploring values, beliefs, and personal aspirations that are disconnected from the traumatic events.

Application of the RGFT method (Reference Group Focused Therapy)

Using a reference group-focused approach: applying the RGFT method focused on reference groups to understand the patient's internal dynamics and how different reference groups influence his behavior and self-perception.

Working on modifying internal reference groups: building more positive reference groups or changing internal patterns created by negative influences.

Integration and continuity of care

Integration of therapeutic insights: Integrating the insights learned during therapy to create healthier internal processes.

Continuity of therapeutic support: ensuring continued support and professional accompaniment, including support groups or additional treatments as needed.

Through this treatment process, the therapist can help the patient change the dynamics of Stockholm syndrome, restore a sense of identity and control, and build healthier experiences and relationships with the world.

Finally, we will offer here the understanding of the syndrome and its treatment while adding the concept of cognitive dissonance to the therapeutic toolbox.

Cognitive dissonance and the model of the "primary self" and the "secondary self"

Cognitive dissonance is a state of psychological tension resulting from the existence of two opposing ideas, beliefs or attitudes. In stressful situations such as kidnapping or capture, the victim experiences cognitive dissonance when he has to deal with a situation in which the figures who threaten his life, such as the kidnappers, also provide him with "small favors" or ensure his survival. The dissonance stems from the contrast between the fear and hostility towards the captors and the gratitude or attachment developed towards them as a way to ensure survival.

Leon Festinger – who developed and coined the term "cognitive dissonance" in his articles and book from 1957

Explaining the emergence of Stockholm syndrome in terms of cognitive dissonance and the proposed model

Dissonance between the threat channel and the attachment channel (in the primary self model):

According to the "Primary Self" model, the victim experiences biological and instinctive reactions to threat and fear, but also instinctive reactions to attachment and seeking security. When the victim begins to develop positive feelings towards the captors (such as gratitude for small favors), a cognitive dissonance is created between the fear and threat and the positive feelings developed as a result of instinctive survival mechanisms.

Dissonance between the internalized characters (in the secondary self model):

Within the framework of the secondary self, the board of internalized characters on the one hand and the group of enemies on the other roughly include characters with positive and negative influence respectively.

In a situation of abduction, the kidnappers may possibly become internalized figures with a contradictory effect: on the one hand threatening figures represented in the enemy group and on the other hand figures represented in the board representing protection and security. The cognitive dissonance appears when the internalized characters on the internalized board have to deal with this contrast.

Solving cognitive dissonance through cognitive distortions and emotional adaptation:

To reduce internal tension (cognitive dissonance), the victim may undergo cognitive and emotional distortions, such as idealizing the abductors or distorting the perception of the threat. These distortions serve as defense mechanisms of the primary and secondary self, allowing the victim to adapt to an emotionally unbearable situation and reduce anxiety and fear.

Treatment of Stockholm syndrome using cognitive dissonance and the proposed model

Identifying the dissonance and understanding it

Recognizing the cognitive dissonance: The first step in treatment is to help the patient recognize the cognitive dissonance he is experiencing. Identifying the gap between the opposite feelings towards the kidnappers (such as fear versus affection) and understanding the reason for the existence of this gap.

Normalization of the response: The therapist explains that these cognitive and emotional responses are natural defense mechanisms in situations of extreme stress, and that this is not a personal failure of the patient.

Cognitive and emotional processing of the dissonance

Working with the reflective self: strengthening the patient's ability to identify his various cognitive and emotional reactions, and encouraging internal awareness of conflicting thoughts and feelings. The introspective reflective self [with the approval of the inner leaders or leader-selves] can act as a mediator that allows two opposing ideas to be held simultaneously and examined more objectively.

Working on cognitive distortions: encouraging the patient to identify the cognitive distortions that were created in order to reduce the dissonance, and work on their correction. For example, understanding the idealization of the kidnappers as a survival response rather than a realistic perception.

Changing hierarchies and internalizations

The restoration of the internal board: work on changing the internal hierarchy of the internalized figures in the board, so that the figures representing the kidnappers will reduce their influence and the protective and positive figures will be strengthened.

Creating new internalized figures: bringing in new internalized figures that match the patient's healthier values and beliefs, thus allowing the patient to build a more supportive and protected internal system. In connection with this, we talked in previous conversations about the importance of building the figure of the therapist in the patient's board of figures as a supporting figure and providing high confidence in the hierarchy of figures in the board.

Building an identity and dealing with dissonance

Building an independent and healthy identity: work on developing a self-identity that does not depend on the internalized characters associated with the kidnappers, thereby reducing their influence on the sense of self and behavior.

Dealing with dissonance gradually: creating situations in which the patient gradually deals with the cognitive dissonance through controlled exposure or cognitive exercises, while providing support and accompaniment throughout the process.

Strengthening the healthy adaptation mechanisms

Developing healthy coping mechanisms: encouraging the use of healthier coping mechanisms to deal with cognitive dissonance and other stressful situations, such as mindfulness, emotional processing, and open communication with the environment.

Strengthening support networks: building a social support network that includes positive and safe figures who can provide emotional support and help create more realistic and healthy perceptions. This will result in the introduction of new supporting characters to the board of introverted characters or in increasing the support capacity and confidence of other characters and raising them in the hierarchy.

Summary

We will suggest that the combination of cognitive dissonance with the model of the "primary self" and the "secondary self" allows for a deeper understanding of Stockholm syndrome and its appearance, and also provides a complex and comprehensive therapeutic framework that aims to reduce the effects of the syndrome and build a healthier and more stable internal and external system in the patient.

Finally, it is also possible to use the "reconciliation" concept mentioned above to understand the syndrome and build its treatment, but it seems that we have expanded too much in this conversation and will stop here.

Until the next time,

yours,

Dr. Igor Salganik amd Prof. Joseph Levine

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Leave a comment