Conversation 69: The concept of the substitute, understanding the “drive” and the role of substitute objects

Greetings to our readers,

The philosophical idea of substitution in the complex fabric of human thought, the concept of "substitute" emerges as both a practical and metaphysical entity. At its core, a substitute is what stands in the place of the other, a character entity or idea that fulfills, replaces or imitates the function of the original. However, to reduce the substitute to a mere placeholder is to ignore its profound implications in ontology, ethics, aesthetics, and epistemology.

Below we will explore the dimensions of the substitute, trace his philosophical genealogy and examine his resonance in contemporary thought.

The ontology of exchange

The substitute works in a dual mode: as a reflection and a deflection. In its reflective capacity, it reflects the essence of the source, striving to imitate its role or presence. However, in its deviation it symbolizes absence – a reminder of what is lost, incomplete or unattainable.

Heidegger's concept of "being" and "being-there" offers fertile ground for examining this duality. Substitution may be perceived as an attempt to restore or approximate an ontological presence, but at the same time it emphasizes the impossibility of complete replication.

For example, a portrait of a loved one. The portrait replaces his physical presence, evoking his essence but it also conspicuously marks his absence.

This duality invites reflection on the nature of reality and representation – an ancient discourse such as Plato's "allegory of the cave", in which the shadows serve as a substitute for the real, and confuse the boundaries between appearance and truth.

The ethics of substitute

Ethical considerations of substitute often revolve around the authenticity of the substitute and its consequences. Substituting one action, decision or entity for another is intrinsically value-laden, and carries implications about trust, responsibility and justice.

Emmanuel Levinas, in his reflections on alternatives and responsibility, touches on substitute through the ethical requirement to prioritize the other. Here, the substitute of the self with the other is not just a substitute but a deep ethical call – to stand by the other in his suffering or vulnerability.

However, ethical dilemmas arise when the exchange violates trust or diminishes the intrinsic value of the source. Replacing real relationships with business relationships, or replacing human work with automated processes, for example, raises questions about respect, autonomy and alienation.

These considerations invite us to examine the moral weight of alternative actions, and to demand a balance between necessity and irreplaceable respect.

Aesthetic substitute: Art and Imitation

The aesthetic field is a fertile arena for the study of substitution, where imitation often straddles the line between homage and forgery. Aristotle, in his "Poetics", advocates mimesis (imitation) as the foundation of artistic creation, and claims that the exchange nature of art allows humans to grasp universal truths through certain representations.

However, the rise of hyper-reality, as described by Baudrillard, complicates this relationship. In a world dominated by simulacra, the substitutes often overshadow the original, creating a reality where the distinction between the authentic and the artificial dissolves. The substitute therefore challenges our aesthetic sensibilities and forces us to investigate the very criteria by which we discern value, originality and beauty.

Epistemological Substitute: Knowledge and Representation

In epistemology, substitute appears in the form of models, symbols and metaphors – tools that represent complex phenomena to make them understandable. A mathematical equation, for example, replaces physical reality, allowing precision and prediction but necessarily simplifying and simplifying the nuances of the source.

Philosophers like Kant emphasize the limits of substitute knowledge. The "thing in itself" (nomenon) remains inaccessible, and human cognition relies on phenomena – substitutes shaped by our sensory and conceptual frameworks. This epistemological substitution, while necessary, invites humility, reminding us of the partiality and constructed nature of human understanding.

Substitute in contemporary contexts

In the modern era, the concept of substitute has taken on renewed meaning amid technological, ecological and social transformations. Artificial intelligence and robotics, for example, raise profound questions about the interchangeability of human intelligence and work and even human being. Can a machine really be a substitute for human creativity, empathy or human decision-making? Or does such a substitute risk dehumanization and ethical erosion?

Similarly, in the context of environmental crises, the search for substitutes – renewable energy for fossil fuels, biodegradable materials for plastic – reflects humanity's attempt to reconcile progress and sustainability. These efforts highlight the dual role of substitution: as a path to innovation and as a reminder of the finite and fragile nature of our original resources.

Substitutes for important human characters

When a substitute is placed in the role of an important human figure – a leader, mentor or loved one – the consequences are profound. The substitute becomes a repository of collective hopes, memories and aspirations, often carrying the weight of what the original embodied. However, such exchange is inherently imperfect. The replacement may be able to preserve the symbolic functions or roles of the original, but it can never fully reproduce the complex humanity, charisma, or life experiences that defined the person.

Philosophically, this act of substitute sheds light on the interrelationship between collective memory and individual uniqueness. The replacement becomes a bridge between the past and the present, offering continuity while emphasizing the irreplaceable nature of the original. This tension invites reflection on the limits of representation and the resilience of human values in the face of loss and change.

Towards a philosophy of the substitute

The substitute, far from being just an aid, turns out to be a deep philosophical structure that intersects with fundamental questions of being, value and knowledge. To engage in substitution is to deal with absence and presence, authenticity and imitation, loss and compensation. It is to confront the limitations and possibilities of replacement, to recognize that every replacement, no matter how perfect, carries the traces of what it replaced.

In adopting the philosophy of the substitute, we are invited to reflect on what is essential, irreplaceable and uniquely human. Such observation not only deepens our understanding of the substitute, but also enriches our appreciation of the original, and urges us to navigate the delicate interplay between the two wisely, carefully and creatively.

Understanding drives and the role of substitute objects

Human behavior is complex, and one of the basic motivations behind our actions is the interplay between urges and the satisfaction from them. From early childhood to adulthood, we learn to recognize our drives – whether they are for nourishment, affection, achievement or intimacy – and seek ways to fulfill them. In psychological terms, drive can be conceptualized as arising from an internal source that compels a person toward a certain action or goal.

This drive is usually aimed at what we can call a "predetermined object", that is, the ideal or original goal of that drive.

An impulse can be defined as a sudden, often subconscious urge to act in response to an internal or external stimulus. These urges are rooted in basic human needs, such as hunger, thirst, sexual satisfaction and emotional connection.

Sigmund Freud, the pioneer of psychoanalytic theory, emphasized that drives are deeply connected to the unconscious and often emerge from the id, the primitive part of the psyche responsible for instinctive desires.

Psychologists classify drives into two broad types:

Primary drives: These are biologically and survival driven, such as the need for food, water and shelter.

Secondary drives: These are socially or culturally influenced, such as the desire for success, recognition or friendship.

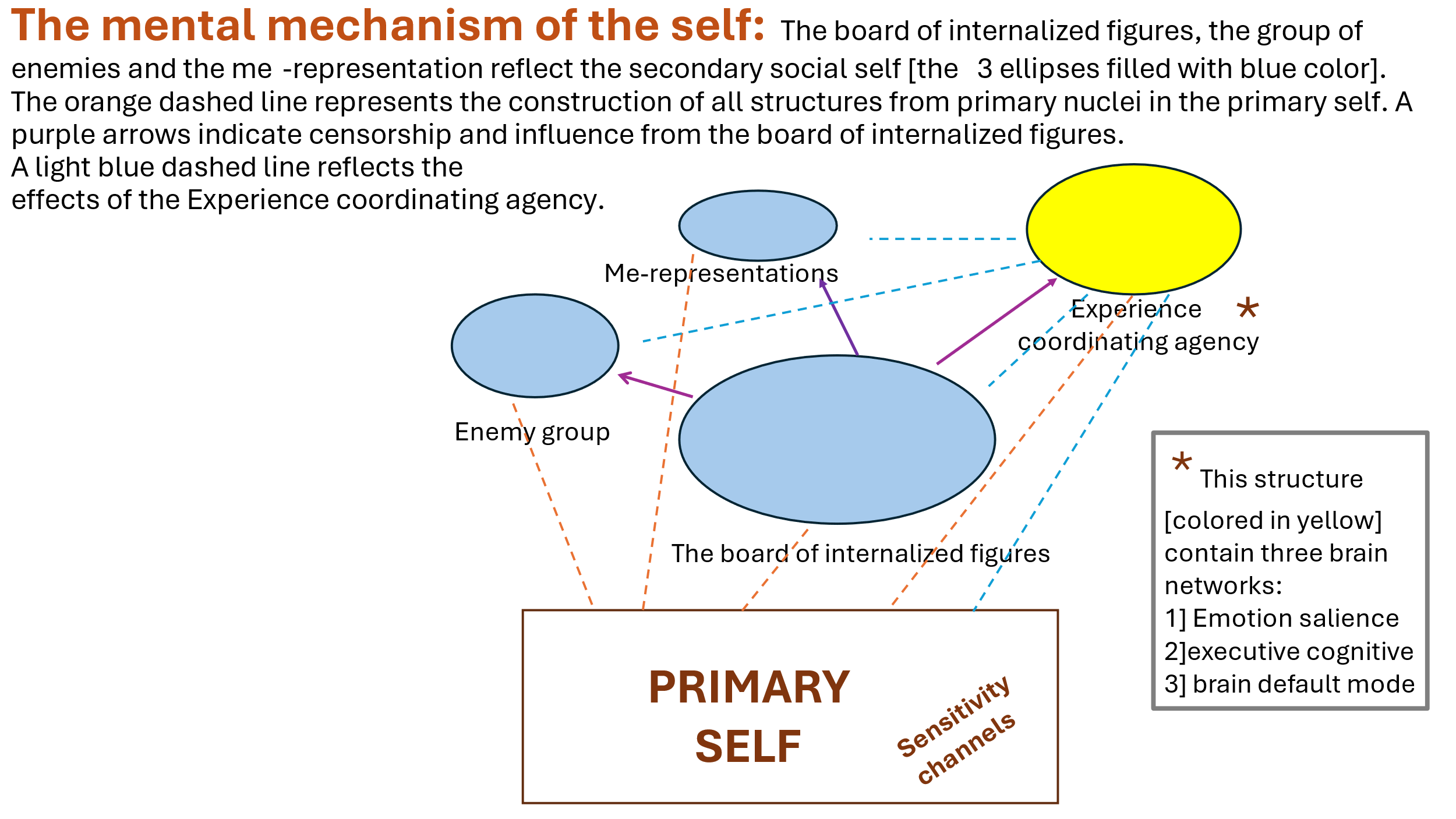

We assume that primal urges mainly have a biological origin and that in the model we are developing these are found in the primary self [see previous conversations]. The secondary drives may also have a primordial biological core, but they are influenced by the characteristics of the board of internalized characters and its leaders and self representations and possibly also by the internalized enemy group [for example, the need for protection].

The role of impulse satisfaction

Satisfying the urge is essential for maintaining psychological balance. When an urge meets its predetermined object—for example, eating when hungry or resting when tired—a sense of relief and pleasure is usually experienced. This fulfillment strengthens the behaviors and creates patterns that guide future actions.

The role of drive satisfaction

Satisfying the drive is essential for maintaining psychological balance. When a drive meets its predetermined object—for example, eating when hungry or resting when tired—a sense of relief and pleasure is usually experienced. This fulfillment strengthens the behaviors and creates patterns that guide future actions.

However, life often presents obstacles that prevent immediate or direct drive gratification. In such cases, the mind looks for alternative ways to relieve the tension. This leads to the concept of the substitute object.

Thus, when the object of the drive is predetermined but is not available – or cannot provide the necessary satisfaction – the person may turn to an alternative object to achieve a similar feeling of relief or satisfaction.

This concept is central to many therapeutic conversations because it illustrates how people adapt creatively when their original needs are unmet or inaccessible.

The nature of drives and predetermined objects

Drives are internal expressions that push us towards satisfying basic needs, such as hunger, security, belonging, love or sexual satisfaction. They can be conscious (eg, feeling hungry and foraging) or operate below our awareness, influencing our behaviors in subtle ways.

In classical psychoanalytic terms, the term "object" often refers to the person or thing toward which the drive is directed. A predetermined object is the primary, ideal, or original goal of the drive. For example, the infant's innate drive to feed is directed toward the caregiver (who provides food and comfort). In adulthood, romantic drive may be directed toward a specific partner who ideally meets one's emotional and physical needs.

The relationship with a predetermined object is often built on biological context, emotional connections, past experiences or cultural ideals. It is "predetermined" in the sense that our psychological makeup and past experiences shape our choice of that object.

When a person cannot access or satisfy the drive with the predetermined object, this creates psychological stress or emotional distress. For example, in the case of a child who craves attention from a parent who is physically or emotionally absent.

Or in the case of an adult looking for a romantic partner who will fulfill emotional needs but remains single or experiences repeated rejection.

In general, we note that humans are resourceful in finding ways to reduce the stress associated with unmet needs. This is where replacement objects come into play.

A substitute object is any person, thing or activity that can partially or fully replace the original predetermined object and provide some degree of relief or satisfaction.

We assume that there can be different degrees of similarity between a substitute object and the original, and speculate that the person will tend to choose the substitute object closest to the original and if it is not found, the search will move to a substitute object that is relatively less close. We hypothesize that if the replacement object is very far from the original, this may involve mental pathology. We will add that in a previous conversation we talked about a transitional object which is apparently a special case of a substitute object.

Thus, replacement objects help prevent the accumulation of frustration and anxiety. For example: an adolescent who feels lonely at home may turn to online forums or social media friendships when meaningful relationships at school are lacking. Or, a person unable to find emotional satisfaction in a romantic relationship may immerse themselves in intense work or creative projects to channel and satisfy their urges in another area.

Or, a person who feels disconnected from family may "adopt" close friends as chosen family, fulfilling the urge for belonging and support.

Psychological theories and explanations

Freudian psychoanalysis

Key idea

Sigmund Freud's theory revolves around drives (eg, libido and aggression) and how these drives seek satisfaction. When the original (predetermined) object of the drive is not available – or the direct expression of the drive is censored by the superego – the mind finds alternative ways to achieve partial satisfaction.

Explanation for a substitute object:

Displacement: the drive is redirected to a more accessible or safer target. If a person cannot express anger towards a parent (the primary object), he may transfer it to a sibling or a peer (the substitute object).

Sublimation: the drive energy is channeled into socially acceptable activities. For example, an unfulfilled sex drive may be "replaced" by artistic or athletic endeavors.

Substitute objects allow people to reduce psychological stress, preventing direct confrontation with forbidden or threatening urges.

Jungian analytical psychology

Key idea:

Carl Gustav Jung introduced concepts such as the collective unconscious, archetypes and the process of individuation. In Jungian theory, people's drives are intertwined with unconscious archetypal images.

Substitute object explanation:

Symbolic Substitutes: Instead of a direct object, the psyche may cling to symbols or archetypal figures that represent missing emotional or spiritual needs.

Projection: Unconscious qualities are projected onto substitute objects, which then become carriers of deep personal meaning or fulfillment.

Substitute objects can serve as catalysts for personal growth and individuation if they are recognized as symbolic expressions of deeper psychological truths.

Adlerian individual psychology

Key idea:

Alfred Adler emphasized the drive for superiority and social interest as central motivations. People develop personal goals and "lifestyles" in response to perceived inferiority or unmet needs.

Substitute object explanation:

Compensation: When a primary goal (object) is unattainable or blocked, the individual may find another occupation or relationship that compensates for the gap.

The creative power of the individual: substitute objects are chosen based on creative strategies that a person uses to overcome feelings of inferiority or social detachment.

Substitute objects reflect the person's desire for success, belonging, or control when the original path to these goals is unavailable.

Behaviorism

Key idea:

Behaviorists, such as John B. Watson and B. P. Skinner, focus on observed behaviors and the environmental situations that shape them. Internal aspects are much less emphasized; Instead, the behavior is seen as a result of learning processes (classical and operant conditioning).

Substitute object explanation:

Contingent reinforcement: If a primary reinforcer (eg, parental approval) is absent, a person may learn to seek secondary reinforcers that serve as substitutes (eg, peer approval, social media "likes").

Generalization: A response to one stimulus may generalize to another stimulus that shares similar cues, effectively making it a substitute.

Why this is important:

Through reinforcement histories, people learn to find alternative sources of reward (substitute objects) when the original reward is unavailable.

Key idea:

Cognitive psychology emphasizes mental processes – such as schemas, perceptions and problem solving. Behaviors and emotional responses are influenced by how we process information and interpret our experiences.

Substitute object explanation:

Schema-guided substitution: When a schema (mental frame) for a desired object or goal is unfulfillable, the individual's cognitive system searches for an alternative that matches certain elements of that schema.

Reducing cognitive dissonance: If the ideal object is not available, people may choose a substitute to reduce the dissonance between "what I want" and "what I have."

Why this is important:

Substitute objects can help maintain cognitive equilibrium and self-consistency by offering a practical "fit" for unmet aspirations or needs.

Humanistic psychology (Maslow and Rogers)

Key idea:

Humanistic psychologists such as Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers focus on personal growth, self-actualization and the realization of human potential. Maslow's hierarchy of needs outlines increasing levels from physiological needs to self-actualization needs.

Substitute object explanation:

Hierarchy of needs: If a person cannot fulfill certain basic needs (eg, love/belongingness), they may replace them by overemphasizing other needs (eg, esteem needs) or activities that provide a temporary sense of worth.

Conditions of value: Carl Rogers emphasized that people may seek substitute relationships or achievements if their core self is not unconditionally accepted by key figures (the "original" sources of validation).

A substitute object can become a springboard for growth (if it fits true personal needs) or a barrier to authenticity if it distracts from deeper, unmet needs.

Attachment theory

Key idea:

John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth proposed that early attachment experiences shape an internal working model of relationships. People with secure interpersonal relationships tend to have more stable interpersonal relationships, while those with insecure relationships may develop alternative strategies to get their emotional needs met.

Substitute object explanation:

Internal Working Models: If early caregivers are inconsistent or absent, the individual's attachment system may seek "substitute caregivers," including friends, romantic partners, or even pets, to fill the need for reassurance.

Protest and despair: An unattainable primary figure (caregiver) can lead to protest (searching for the primary object), and if unresolved, cause a transition to substitute figures that provide partial comfort or emotional regulation.

Why this is important:

Substitute attachment figures or substitute objects can help people cope with anxiety and loneliness; However, they may also perpetuate patterns of anxious avoidance or clinging if the underlying problem is not addressed.

Cognitive dissonance theory: Festinger's cognitive dissonance theory holds that when there is a conflict between a drive and its elusive object, people may justify using a substitute to reduce psychological discomfort. For example, someone who is unable to purchase a coveted luxury item may convince himself that a cheaper alternative is just as satisfying.

Self-Determination Theory: This theory emphasizes the importance of autonomy, the ability to act and personal motivation. When one of these needs is thwarted, people may seek substitutes that mimic experiences related to these aspects. For example, a person who feels incompetent at work may immerse themselves in video games where they can experience control.

Social learning theory: Bandura's social learning theory emphasizes the role of observation and modeling in behavior. People may adopt substitute behaviors or substitute objects that they see others use successfully to cope with unsatisfied urges.

Existentialist Psychology: Existential theories suggest that replacements often arise from a deeper grappling with existential dilemmas, such as a search for meaning or grappling with freedom and responsibility. For example, someone struggling with a lack of purpose may turn to excessive work to fill the void.

Drive Reduction Theory: Rooted in the work of Clark Hull, this theory assumes that behavior is driven by the need to reduce internal tension caused by unmet drives. When the primary object of satisfaction is not available, substitutes that lower this tension become attractive alternatives.

The concept of the "false self" as a substitute according to the British psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott.

The concept of the "false self" has roots in both psychoanalytic and existential thought, although it is most famously developed and articulated by British psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. In short, the false self arises when a person feels the need to adapt or conform to external demands so thoroughly that their behavior and attitudes become disconnected from their true inner sense of self.

This inner sense, often referred to as the "real self," hides behind a veil constructed for social, family, or cultural acceptance. Philosophically, this phenomenon is closely related to the problem of authenticity – how can a person be true to his existence in a world that places countless expectations and pressures on us.

Existentialists, and phenomenologists – such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger – addressed similar concerns in their discussions of "inauthentic being" and "bad faith". For Sartre, bad faith occurs when someone deceives himself into believing that he is limited by external factors, denying his basic freedom and responsibility.

In a similar vein, Heidegger spoke of the "I-them", the aspect that unthinkingly conforms ourselves to social norms and conventions, abandoning our potential for authentic selfhood.

These philosophical views echo the idea that we can adopt a self that will act as a substitute: it does not represent a true, self-oriented way of being, but instead serves the expectations of others or submits to social conformity.

Thus, whether described in psychoanalytic or existential terms, the false self stands as a strategy for navigating a reality where one cannot (or believes one cannot) live as one really is.

And while this approach may bring security or acceptance in the short term, in the long term it can create a situation of ongoing internal conflict. People may reach adulthood feeling that the identity they project is not really theirs, and feel a deep split between their outer "persona" and an unfamiliar inner core.

When we call the false self a "substitute," we point to the idea that it acts as a substitute for authenticity when authenticity is deemed too dangerous or unsupported by the environment. This alternate self is not only a mask, but can become the only identity we know how to protect.

On the one hand, it helps ensure social acceptance and emotional balance; On the other hand, this mask stifles spontaneity, creativity and the capacity for true intimacy.

Over time, the person may lose touch with the original reason for creating the replacement self, leaving them unsure of how to reclaim their authentic individuality.

This conception of the false self as a substitute also illuminates the potential for transformation. Recognizing the false self as it is – a protective but limiting adaptation – can offer an opportunity to dismantle or integrate it.

Indeed, many therapeutic and philosophical practices focus on bringing one's unconscious strategies into consciousness, examining how they have served or limited the individual, and examining paths toward a truer and more uncontradictory sense of identity.

The theory of the self and the internal reference groups

This is fed by our concepts and assumes a model for the life of the mind or for the self, the outline of which appears below:

The theory assumes the existence of a primary self consisting of innate biological structures and instincts that form the innate basis of the parts of the personality and it also included the cognitive processes and the emotional processes. This primary self has its own dynamics during a person's life and is subject to changes with age, following diseases, traumas, drug consumption, addiction, etc.

Both the instincts and the drives are the basic needs in each person and they change according to different periods of development. Within the primary self there is the potential for instrumental abilities that are innate, but they can also be promoted, or on the contrary, suppressed through interaction with the environment. [See below] The primary self also has cognitive abilities that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment during the first years of life.

In addition, it includes the temperament and emotional intelligence that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment in the first years of life. And finally, it includes an energy charge that is mostly innate but can be suppressed through the influence of the reference groups, as well as through various situational factors. The primary self also includes the seven personal sensitivity channels: Individual Sensitivity Channels (ISC) which reflect our individual reactivity in response to stressors (both external and internal).

So far we have identified seven channels of sensitivity: 1. Sensitivity regarding a person's status or social position (status channel) 2. Sensitivity to changes in norms (norm channel) 3. Sensitivity regarding emotional attachment to others (attachment channel) 4. Sensitivity to threat (threat channel) 5. Sensitivity for routine changes (routine channel) 6. Sensitivity to a decrease in energy level and the ability to act derived from it (energy channel). 7. Proprioceptive channel, sensitivity to the individual's personal reactivity towards internal sensations from his body or hypersensitivity in one of the senses to external stimuli.

From the primary self, a number of superstructures gradually develop from innate nuclei that form a fundamental basis for development [with the interaction of the baby, and later the person during his life, with the figures in his environment]:

The Experience Coordinating Agency:

A structure found in the primary self, includes three brain networks: the emotional salience network, the executive cognition network, and the default mode network.

The role of the mechanism: scanning and evaluating the internal and external arrays and directing attention to the relevant network.

Board of Internalized Characters:

A collection of influential figures from life, but also imaginary virtual influential figures, as well as the representations of the subculture arranged in a hierarchy, with continuous dialogue and conflicts.

The figure of the "leader self" (like the "dictator self") affects decision-making and internalization of information.

Internalized Enemies’ group:

A group of negative internalized characters that threaten the person. The influence of these characters is caused by traumatic events.

If the enemy figures are dominant, this may indicate mental pathology.

Usually the internal leader in the board of directors pushes certain figures who oppose his positions to this group.

Self-representations evoke in the developmental process of man at different stages of life (as a child, teenager, adult).

Substitute object explanation: According to this theoretical background

Within the framework of the secondary self, the board of internalized figures, the representations of the self, the group of enemies, and the channels of sensitivity are structures that influence the way a person deals with internal urges, traumas, and losses. Substitute objects and characters, as tools for psychological coping, are influenced by these structures and provide a context for understanding the choices a person makes in his life.

The board of internalized figures and the relation to substitute objects

The directorate of internalized figures is a collection of internal figures that represent significant people from human life (parents, caregivers, teachers, friends) or imaginary figures and representations of the subculture whose influence has been built up throughout life. These figures are arranged in a hierarchy and influence decision-making processes, selection of substitute objects and interpretation of reality.

As mentioned, the secondary drives are particularly influenced by the board of internalized figures and its leaders, when the subculture represented as a schematic figure in the board plays a significant role in this.

Positive figures as choice guides: Positive internalized figures may guide the person in choosing substitute objects that promote psychological balance. For example, an internalized figure of a supportive parent may encourage a person to turn to creative activities as a substitute or to friends when dealing with feelings of loneliness.

Negative figures as intensifiers of pathology: negative internalized figures, such as a critical parent figure or an abusive partner, may lead the person to choose unhealthy substitute objects, such as drug use, destructive behaviors or dependence on unsupportive people.

Self-representations and their influence on the use of substitute objects

Self-representations describe the way a person perceives himself at different stages of life (child, teenager, adult). These representations, which develop while interacting with the environment and the significant characters, also shape the choice of replacement objects.

Healthy self-representations: A person with healthy and mature self-representations will tend to choose substitute objects that fulfill the urge in a constructive way, such as strengthening social relationships or developing hobbies.

Distorted self-representations: Underdeveloped or distorted self-representations may cause a person to turn to substitute objects that provide temporary relief but maintain harmful behavior patterns.

The internalized enemies’ group and its role in stressful situations

The enemy group represents negative internalized characters that threaten the person and as a rule were pushed into this group by the leader on the board. These characters are created following traumatic experiences or they categorically oppose and threaten the positions of the internalized board leader. The influence of the group of enemies is especially evident in situations of stress and threat, when the person may look for substitute objects that will help him deal with the internal threat that these characters evoke.

Substitute objects as a coping mechanism: In cases where the enemy group is dominant, the person may turn to substitute objects to blunt the sense of threat.

Risk of creating pathology: when the enemy group dominates, and the board group is relatively passive, the choice of substitute objects to meet protection needs can become compulsive and maintain a sense of worthlessness or loss of control.

Dynamics between the structures: the process of choosing a substitute object

The structures of the board of internalized figures, the representations of the self, and the group of enemies work together in a complex process that influences the choice of the substitute object.

The influence of the internalized figures: The board of internalized figures influences the interpretation of the situation and the possible solutions. Supporting characters may offer healthy solutions. Negative figures may result in an unconscious choice of destructive substitute objects.

Self-representations as an internal compass: Self-representations affect the feeling of self-worth and the ability to choose a substitute object that provides relief without harming personal growth.

Substitute objects and figures as a mechanism of adaptation and repair

Substitute objects and characters play a dual role:

Adaptation mechanism: they help deal with feelings of deprivation, anxiety or loneliness, for example by turning to a new supporting figure or creative occupation.

Corrective process: When the patient succeeds in recognizing the influence of the enemy group and using the positive internalized figures, pathological patterns can be converted into healthy and beneficial choices.

Allows professionals to more accurately diagnose the sources of mental distress and help patients choose substitute objects that will provide relief without preserving harmful patterns.

Integrating this approach into psychological treatment may empower patients, allow them to build positive and meaningful relationships and support a healthy and integrative developmental process.

The sensitivity channels and a substitute object: when these reveal a higher sensitivity in the individual, then in the case of the lack of a target object for the impulse, the vital need for an urgent finding of a substitute object will arise, even if it is essentially far from the target object. In other words, the threshold for containing the lack of a target object drops considerably.

We note that as a rule a person can have healthy versus unhealthy substitute objects.

When substitutes are adaptive: they can provide temporary or partial relief when a person is dealing with loss, isolation, or life transitions. Healthy substitutes may include supportive friendships, hobbies, mentoring or therapy – avenues that promote personal growth and resilience.

When the substitutes become maladaptive

In some cases, a person's use of a substitute object can lead to unhealthy patterns, such as addiction or dependence. For example, reliance on drug use or compulsive behaviors or pathological attachment to another person to relieve emotional distress. We will also note that overreliance on substitute relationships can also create a dynamic of interdependence or prevent the individual from addressing basic emotional needs that remain unsatisfied.

On the other hand, long-term avoidance of addressing the original desire or urge can lead to deeper problems, including chronic dissatisfaction, anxiety, or depression.

Therapeutic implications

Recognition and Awareness: A key step in treatment is to help patients identify their unmet needs and the drives that drive their behaviors. Recognizing predetermined objects and the existence of substitute objects is essential for deeper self-understanding.

Healthy Coping Strategies: Therapists guide patients toward healthier forms of drive gratification. This could include building new supportive relationships, exploring hobbies, or cultivating self-care practices. Encouraging constructive forms of substitution (eg, art, sports, volunteer work) can also moderate the negative impact of unfulfilled drive.

We note that when the predetermined object really cannot be substituted (for example, the death of a loved one), the treatment focuses on acceptance and building resilience, with the understanding that partial replacements can still be significant in one's life.

In RGFT therapy [see previous conversations] it is possible to create awareness in the patient of substitute characters that populate his board of characters and sometimes his representations of the self [FALSE SELF] and even the group of enemies [here we mention the concept of FALSE ENEMY without expanding it] while giving him the freedom to decide whether to change them, change their position in the hierarchy and more.

1. Freud, S. (1923). The Ego and the Id. Hogarth Press.

2. Jung, C. G. (1966). Two Essays on Analytical Psychology (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

3. Adler, A. (1927). Understanding Human Nature. Greenberg.

4. Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and Human Behavior. Macmillan.

5. Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. Meridian.

6. Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396.

7. Rogers, C. R. (1961). On Becoming a Person: A Therapist's View of Psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin.

8. Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

9. Ainsworth, M. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

10. Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Prentice-Hall.

That's it for now,

yours,

Dr. Igor Salganik and Prof. Joseph Levine

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Leave a comment