Convesation 72: Cognitive dissonance, the influence of environmental pressures and the multi-layered model of Self

Hello to our readers,

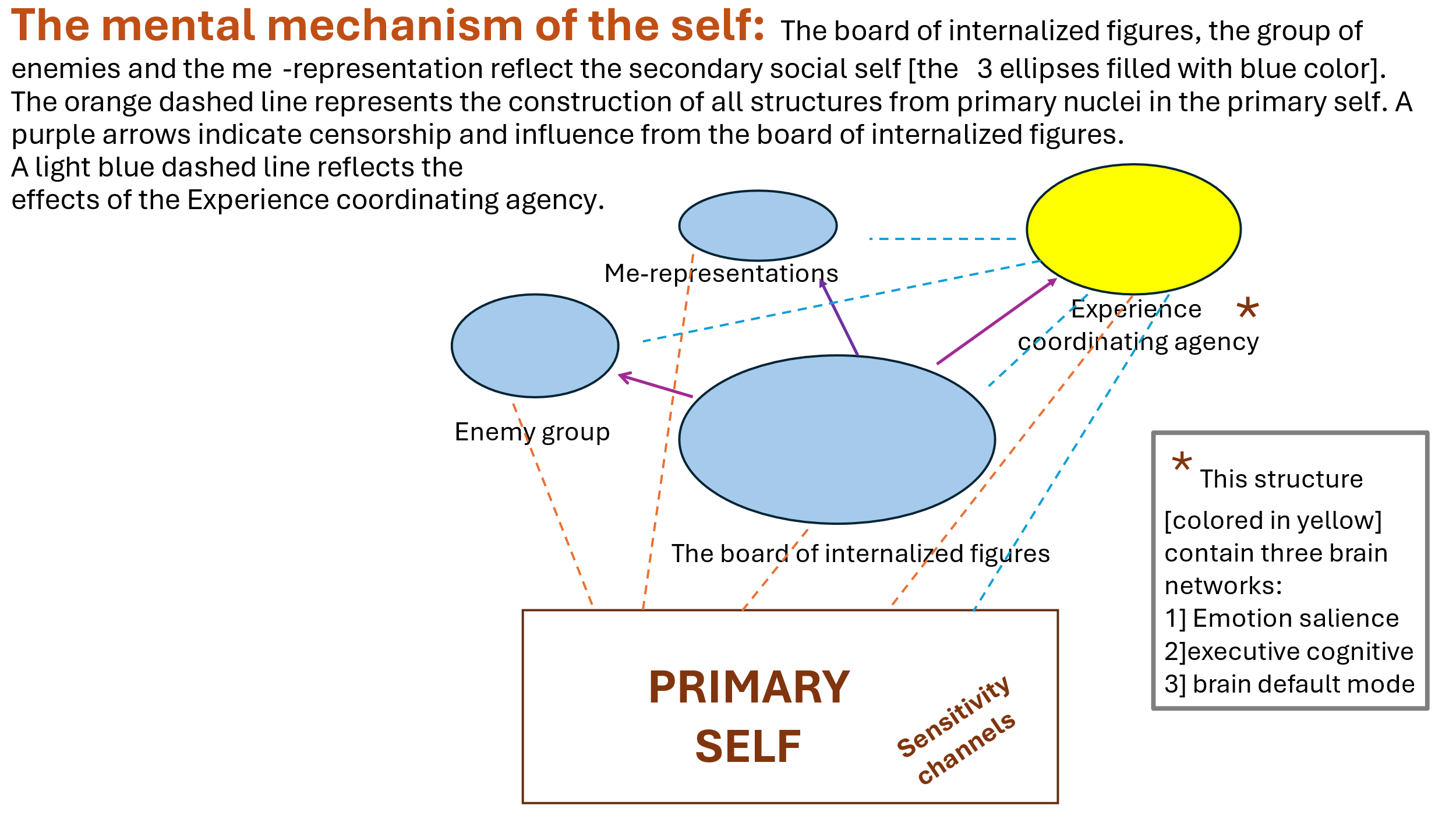

In our model, the self includes the elements of the human mental apparatus. The model first assumes the existence of the "primary self", which is in fact the basic biological core consisting of several innate structures and subject to increasing development during life, this self includes the instinctive emotional and cognitive parts of the person. The primary self uses the reservoirs and mechanisms of emotion, memory and cognitive abilities and it contains primary nuclei for the future development of other mental structures.

Let's first refer to the primary self (Biological Predestined Core): the primary self consists of innate biological structures and instincts that form the innate basis of the parts of the personality and it also included the cognitive processes and the emotional processes.

This primary self has its own dynamics during a person's life and is subject to changes with age, following diseases, traumas, drug consumption, addiction, etc.

Both the instincts and the basic needs in each and every person change according to different periods of development and aging – (hence their effect on behavior) and may change through drugs, trauma, diseases and more. Within the primary self there is the potential for instrumental abilities that are innate, but they can also be promoted, or on the contrary, suppressed through the influence of the reference groups.

The primary self also has cognitive abilities that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment during the first years of life. In addition, it includes the temperament and emotional intelligence that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment in the first years of life.

And finally, it includes an energy charge that is mostly innate but can be suppressed through the influence of the reference groups, as well as through various situational factors.

The primary self also includes the seven personal sensitivity channels: Individual Sensitivity Channels (ISC) which reflect our individual reactivity in response to stressors (both external and internal). So far we have identified seven sensitivity channels:

1. Sensitivity regarding a person's status and location (status channel)

2. Sensitivity to changes in norms (norms channel)

3. Sensitivity in relation to emotional attachment to others (attachment channel)

4. Sensitivity to threat of any kind – physical, economical, etc., (threat channel)

5. Sensitivity to routine changes (routine channel)

6. Sensitivity to a drop in energy level and the ability to act derived from it (energy channel)

7. Sensitivity to proprioceptive stimuli coming from the body (proprioceptive channel)

From the primary self, a number of superstructures continue to develop from innate nuclei that constitute a basis for the development of the infant and later the person throughout his life with the characters around him: three structures that together make up the secondary self or the social self, these include:

A] The group of the collection of internalized characters that we will metaphorically call the Board of Internalized Characters,

B] The group of internalized enemies

C] The group of the internalized self-representations.

The group of internalized characters that we will metaphorically call the board of internalized characters.

The board of internalized figures consists of the internalizations of influential figures in person’s life, arranged in a hierarchical order [as mentioned, we metaphorically call the group of these internalizations the board of internalized figures or the board of directors or the board of internal figures].

These characters have a continuous dialogue between them and sometimes even conflicts, while one or more internalized characters have the greatest influence on the individual's attitudes, feelings and behavior, which we called the "leader self" [a character formerly also called the "dictator self", see previous conversations].

The attitudes of the inner leader play a central role in making decisions about the internalization of information and figures. He decides whether to reject the internalization or, if accepted, in what form it will be internalized. In other words, in a sense, we assume that this influential figure is also a form of internal censorship.

It should be emphasized that these are not concrete hypotheses regarding the presence of internalized figures in the inner world of the individual as a kind of "little people inside the brain", but rather in their representation in different brain areas whose nature and manner of representation still requires further research.

We will also note that although we call this figure the "inner leader", with the exception of a certain type, his characteristics are not the same as those of a ruler in a particular country, but rather that this figure is dominant and influential among the "directorate of figures".

We note that the events and characters in the external world maintain a kind of dialogue through the mediation of the "experience coordinating agency" [see previous conversations] with the internalized characters in the board [or with the internalized group of enemies – see below] and may affect the expression and sometimes even the hierarchy of the characters in the board of internalized characters.

In addition, it is possible that similar to short-term memory, parts of which are transferred to long-term memory, also with regard to the internalization of figures into the board of directors, there is a short-term internalization that, depending on the circumstances, the importance and duration of the character's influence, will eventually be transferred to long-term internalization in the set of internalized characters.

Below is the structure of the board of internalized characters: This board consists of "secondary selves" that include the following types:

1] Representations of internalized characters that originate from the significant characters that the person was exposed to during his life, but as mentioned, there may also be imaginary characters represented in books, movies, etc. that greatly influenced the person.

2] internalized representations of "subculture" [subculture refers to social influences in the environment in which a person lives and are not necessarily related to a specific person].

We note that the individual is usually not aware that his actions, feelings and attitudes are caused by the dynamic relationships between these structured characters.

We will add that internalized key figures in the board of directors [usually human], usually refer to the significant people in a person's life who played central roles in shaping his attitudes, beliefs, values and self-concept. These figures may include family members, friends, mentors, teachers, or any other influential person who has left a lasting impression on the person's psyche.

Sometimes, these will also include historical, literary and other figures that left a noticeable mark on the person and were internalized by him. The term "internalized" implies that the influence of these key figures has been absorbed and integrated into the individual's thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors. This internalization occurs through the process of observing, interacting with, and learning from these important people.

As a result, the individual may adopt certain values, perspectives, and approaches to life that mirror those of the influential figures. These internalized characters can serve as guiding forces in decision-making, moral thinking and emotional regulation.

The Internalized Enemies’ Group

Now we will note in addition that from the primary self there arises and is built from a potential nucleus at birth a structure that we will call the enemies’ group.

Thus, in addition to the board of internalized characters, in the social self there is also the "group of enemies" and more precisely the "group of internalized enemies", this is the place where the characters that significantly threaten the person are internalized while the dominant characters in the board of characters prevent them from entering and being internalized within the board of characters (we assumed the existence of this group in the last year in light of thinking about the evolutionary need for the animals and for man to create such a group for their survival, see a broad reference to the subject of enemies below).

The characters in the "group of enemies" are characters with a negative emotional value and are represented schematically relative to the characters in the board of internalized characters.

We note that usually the transition between the group of the board of directors and the group of enemies is not common and even rare and usually happens following the traumatic or threatening event for a person.

The group of internalized self-representations

In addition, from the primary self, as mentioned, a supergroup of self-representations develops in the different periods of life [for example, the self-representation as a child, as a teenager, as an adult, and more], including the representation of the body.

The representation of the self in a certain sense is also a kind of container for the flow of information of emotional attitudes and behaviors from the dynamics in the board of characters.

Below we will bring again the illustration of the model of the self that includes the structures mentioned above and the mutual effects between them:

Thoughts about the development of the components of the model during the life of the individual

Having said this, we note that similar to the theories of object relations, we believe that in the infant there are first a positive representation with a positive emotion for the carer and breastfeeding character in the internalized characters’ board and another representation that is negative with a negative emotion for the carer and breastfeeding character, when there are probably few such figures with such a double representation as the mother and the father.

These dual representations will gradually merge into one integrated representation over the next few years. In fact, we believe that it is the emotion that enables the coalescence of a character or object into a negative representation around a negative emotion or a positive one around a positive emotion. Why, then, was there an integration of these two later in life into one representation?

You will ask why there is no more splitting, for example, into a negative emotion of anger and a negative emotion of sadness or depression, into a positive emotion of joy, or into a positive emotion of love, and the like.

Here we will answer that a variety of common features of the character whose core is the representation of the face [see previous conversations] contribute to the integration and combination of the negative and positive character.

But there may be pathological cases such as for example in borderline personality disorder [see previous blog] where the split into a positive image and a negative image will remain in varying degrees when the dominant emotion in the sufferer of the disorder brings up one or the other representation.

In another case of a multiple personality disorder, it is possible to continue splitting into many characters as was asked before and thus discussed in a separate article.

By the way, in the baby at the age of 8 months or so, a fear of strangers appears. We believe that at this stage the board of internalized characters begins to form first integrated characters, on the one hand, and on the other hand, another group that we call the enemies’ group, where the negative representations of the characters are gathered.

At the age of 8 months, more numerous and relatively superficial representations of new people, strangers and strangers, first move to the enemies’ group for protection, and only if the mother and her positive representation as the leading figure within the board of directors appears with positive behavior towards the stranger, she can calm the fear in front of the stranger by saying, for example, "This is David Moshe, don't be afraid, etc.

This group we call the "enemies’ group" into which characters who threaten man in a significant way are internalized and whom the dominant characters in the character board prevent from entering and being internalized within the characters’ board [this group is not shown in the figure above and recently [in the last year] we assumed its existence in light of thinking about the evolutionary need in the higher animals and up to man to create such a group for their survival].

The characters in the enemies’ group are characters with negative emotional value. We note that usually the transition between the board group and the enemy group is usually rare and will happen following the traumatic or threatening event for a person.

We hypothesize that the board of internalized characters usually completes its development during adolescence along with the increasingly developing experience coordinating agency and reaches a significant completion with adulthood but can continue to develop further during the rest of life.

Similar to the representation of the mother in a positive or negative way in the infant, the representation of the self, which is also initially double and includes a positive and negative representation, develops from a primordial nucleus in the primary self. These two representations are increasingly merging with development.

At the same time, from a basic nucleus in the primary self, the experience coordinating agency is gradually developing.

Each of the internalized figures in the board of figures and the group of enemies and the group of self-representations have their own attitudes.

While the figures of the leader or leaders in the internalized board of directors exemplify the highest and most dominant positions in the hierarchy of figures in the board of directors, they may exercise censorship on figures who will or will not join the board of directors if their attitudes are contrary to those of the leader or leaders and sometimes will even join the enemies’ group if they pose a significant threat to the internalized leader or leaders in the board of directors.

In general, the classification of attitudes can be understood as the way in which these internal contents of the individual shape his perceptions, feelings and behaviors in relation to the social world.

These positions function similarly to operating systems – they not only store information, but also determine how incoming stimuli are processed and how responses are generated.

Within them, all attitudes are divided into three main categories: relational, perceptual and conduct attitudes.

Relational attitudes

Relational attitudes concern the emotional evaluations that people attribute to people, objects, events, or even abstract concepts. These attitudes express how much we love, fear or even loathe something, and form part of the basis of our interpersonal relationships.

The strength of these attitudes is directly related to the meaning we attach to the subject they are attached to. For example, how we feel about close family members versus strangers is mediated by our relational attitudes, which in turn affect our social roles. Relational attitudes are influenced by many factors, including personal experiences, logical thinking, and social influences that strengthen or challenge our emotional bonds.

The attitudes are also related to the function of the sensitivity channels – such as those related to status, attachment and threat – which help determine the emotional valence (positive or negative) and the strength of these attitudes.

Perceptual attitudes

Perceptual attitudes are more cognitive in nature. They include the mental frameworks or hypotheses that people develop to understand both the physical and social world. Essentially, these attitudes act as lenses through which we interpret and organize our experiences.

Whether derived from personal encounters or acquired from social reference groups, perceptual attitudes guide our assumptions about cause and effect, enabling us to predict and navigate future events.

They contribute to what is sometimes called a "worldview" or "Weltanschauung" – an integrated network of beliefs that filters incoming information.

Perceptual attitudes also provide the basis for prediction and decision-making, balancing social truths against individual experiences. The experiential coordination mechanism is affected by this type of experiences.

Conduct (or action) attitudes

Conduct attitudes, sometimes also described as instrumental action attitudes, refer to behavioral algorithms and instructions that people follow in different social contexts.

These attitudes are directly related to group norms and expectations set by significant social groups or reference groups. They translate the emotional and cognitive evaluations from relational and perceptual positions into concrete actions.

For example, the norms governing behavior in a workplace or within a family are based on conduct attitudes.

These approaches are often less flexible than their relational and perceptual attitudes’ counterparts because they are tied to established rules and social conventions. Consequently, while perceptual attitudes may evolve gradually with new experiences or learning, conduct attitudes tend to be more stable and relatively resistant to change unless a change occurs. significant in the basic social or emotional landscape.

Interrelationships and dynamic interaction

Although classified separately, these approaches are deeply interrelated. A person's emotional (relative) response to an event can trigger specific cognitive (perceptual) evaluations, which are then translated into conduct (action) attitudes.

Feedback from the environment may strengthen or change each of these types of attitudes, emphasizing the dynamic interrelationships between them. For example, a traumatic personal experience (experiential stimulus) may initially change perceptual evaluations; However, over time, the social attitudes picked up from influential reference groups may resist or moderate the initial change.

This dynamic highlights the complexity of shaping and changing attitude, where social influences, personal experiences, and inherent biological factors all contribute to shaping our overall attitude toward the world.

In conclusion, understanding the classification of attitudes into relational, perceptual and conduct types provides a comprehensive view of how people process information and interact with their environment.

Each category plays a separate role – emotional, cognitive and behavioral – but together they create an integrated system that affects social perception, personal adaptation and group dynamics.

Cognitive dissonance and the internalized characters’ directorate

The concept of cognitive dissonance was first proposed by the psychologist Leon Festinger in 1956. It is a situation of contrast between positions or between a position and an action derived from another position.

Cognitive dissonance expresses an inconsistency between any elements of knowledge, attitude, emotion, belief, or value, as well as a goal, plan, or interest.

The theory of cognitive dissonance holds that conflicting cognitions serve as a driving force that forces the human mind to acquire or invent new thoughts or beliefs, or to change existing beliefs, in order to minimize the amount of dissonance (conflict) between cognitions [see Wikipedia entry on cognitive dissonance].

In other words, the theory is based on the idea that people strive for internal consistency and harmony in their beliefs and attitudes. When there is inconsistency or conflict, they experience discomfort, and this discomfort motivates them to resolve the inconsistency by changing their beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors.

Although reducing cognitive dissonance may make it easier for a person, some of the ways to reduce cognitive dissonance involve distorting the truth, which can lead to wrong decisions. Festinger suggests that the dissonance can sometimes be resolved by finding and adding a third piece of information relevant to both beliefs.

Festinger proposed that people are motivated to reduce this dissonance and achieve a state of cognitive consistency through the following ways:

Changing Beliefs: People may change one or more of their beliefs to make them consistent with each other or with their behavior.

Acquisition of new information: People may seek new information that supports their existing beliefs or helps justify their behavior.

Minimization: People may downplay the conflicting beliefs or behaviors, actually convincing themselves that the inconsistency is insignificant.

Seeking social support: People may seek support from others who share similar beliefs or engage in behaviors consistent with their own, providing a sense of validation.

Behavioral modification: Changing a person's behavior to match their beliefs or attitudes is another way to reduce cognitive dissonance.

It is important to note that cognitive dissonance can manifest itself in different situations. Some common types include:

Belief-Achievement Gap: When a person's beliefs conflict with their perceived level of success or achievement.

Free-choice dissonance: Arises when a person chooses between two or more attractive alternatives, leading to discomfort about the rejected options.

Effort-justification dissonance: Occurs when a person goes through a difficult or unpleasant experience to achieve a goal, resulting in a need to justify the effort expended.

Post-Decisional Dissonance: Occurs after a decision has been made, causing discomfort about the potential negative aspects of the chosen option and the positive aspects of the rejected alternatives.

While cognitive dissonance is an established and accepted concept in psychology, like any scientific theory, it is not immune to criticism or debate. Most psychologists and researchers in the field accept the basic principles of the cognitive dissonance theory proposed by Leon Festinger, but there may be differences in emphasis or interpretation.

Some researchers have expanded or modified the theory to address specific nuances or integrate it with other psychological frameworks. In addition, there are ongoing debates about the boundary conditions of cognitive dissonance, the role of cultural factors, and the extent to which cognitive dissonance can explain various phenomena.

We suggest that at least some of the cognitive dissonance situations can be explained by the theoretical background summarized above.

Let's take for example a person who believes in equality for all and civil rights including freedom of speech, who lives in a tyrannical regime that suppresses civil rights and cultivates a ruling class.

That is, here there is a large external group [the dictatorial state] whose values and laws are opposed to the positions of the internalized group [the internal board of directors] within the individual. In this case, the individual complies with the laws of the country lest he be swallowed up, since in this situation there are usually very severe sanctions for disobeying the regime's laws and regulations.

Here the individual experiences cognitive dissonance, one of the solutions of which is the gradual adoption of the positions of the dictatorial regime.

What actually happens here is that the representatives of the large external group [the state in this case] are internalized by the individual and take over the "directorate of internalized figures" and a new internalized leader [in this case a dictator] is created who expresses the values of the state and pushes back the previous internal leader or leaders.

This often happens in sects with strict rules and a charismatic leader who dictates strict rules of obedience with severe sanctions for those who deviate from them.

There may also be another possibility where extraordinary external circumstances [traumatic for example] require behavior that is not acceptable by the internal leader under normal circumstances, behavior whose purpose is survival and the preservation of life.

Here another figure or figures in the internalized board [or a new influential internalized figure or figures] advocating the necessary behavior will rise in the hierarchy and reduce the influence of the internalized inner leader in order to reduce the cognitive dissonance and bring about a change in attitudes and behavior that the individual will express.

That is, one possibility is a conflict between the individual's positions [expressed by the influential figures in his internalized figures' board] and the positions of a large external group, whether a sect or a state with strict sanctions and the like, and a second possibility is a situation [for example survival] that requires behavior that is not acceptable in normal times.

We will now take a step forward in the discussion, and note that a person has different roles in his life, for example as a professional, a father, as a member of a family, as a member of a certain social group, as a member of a certain nation and more. Or about a woman as a professional, as a mother, as a daughter of parents, as a member of a social group, as a daughter of a certain nation and more.

We believe that for each such position, a subgroup with its own leader or leaders is created in the broad group of the board of internalized characters.

For each such subgroup in the board of directors, in certain cases there may also be a subgroup in the group of enemies and sometimes even in the group of self-representations.

We note that each such subgroup has its own attitudes and when there is an inadequacy or contradiction or conflict between attitudes of these different subgroups, cognitive dissonance will be created.

Below are thoughts that combine Festinger's cognitive dissonance theory with the model of self data presented above.

While Festinger's work (Festinger, 1957) is the cornerstone of cognitive dissonance theory, the thoughts below also incorporate the self model that conceptualizes the self as a dynamic interrelationship between a biological core [primary self] and various internalized substructures that grow structurally on top of this core.

Below we explore how cognitive dissonance may arise when conflicting internal representations come into contact with external triggers and stressors.

Cognitive dissonance in a multi-level model of the self: combining Festinger's theory with a multi-level structural framework of the self:

Cognitive dissonance, as originally formulated by Festinger (1957), describes the psychological discomfort experienced when a person holds two or more conflicting cognitions.

Below we will combine Festinger's basic theory with the detailed model of the self that assumes a multi-layered structure of the self. The aforementioned model consists of a "biological core" (or primary self) and emergent intrapsychic structures – including an internal "board of directors or “board of significant figures”, an internalized “enemies’ group” and a group of self-representations – that maintain a dynamic interaction throughout life.

Through this combination we discuss how conflicts between values internalized by the characters in these groups and external constraints (for example, living under an oppressive regime) create dissonance, and how the reorganization of internal hierarchies may serve as a mechanism to reduce dissonance. The discussion examines both the theoretical and practical implications of such intrapsychic dynamics.

Relational Attitudes: Emotional Appraisals

As mentioned, relational attitudes refer to the emotional evaluations that people hold towards objects, people or abstract concepts. They are characterized by emotional responses—such as affection, fear, or aversion—that are central to interpersonal interactions. In the model, these attitudes are related, among other things, to the "internal board", where influential internalized characters (or representations) shape the emotional valence of experiences.

For example, an internalized nurturing figure may promote, for example, a positive relational attitude toward egalitarian values, while another internalized authority figure may contribute to negative emotional evaluations when faced with opposing ideas.

When external circumstances (such as oppressive social norms) contradict these internal emotional evaluations, cognitive dissonance may arise. The dissonance prompts a reappraisal of the emotional meaning attributed to these values (Harmon-Jones & Mills, 1999).

Perceptual attitudes: cognitive schemas

Perceptual attitudes are mainly cognitive in nature as mentioned above. They consist of schemes through which people interpret their experiences and the world around them. In the proposed self-model, these attitudes function as "lenses" that shape one's worldview (similar to what some theorists describe as "Weltanschauung"). They organize information based on past experiences and learned social norms, thereby guiding expectations and perceptions about future events.

When the perceptual positions of the individual collide with external realities – for example, when the scheme of cognitive freedom encounters the strict constraints of an authoritarian state – a situation of cognitive dissonance can occur. This dissonance is the product of a mismatch between one's internal cognitive quantities and the information or rules imposed by the external environment.

Conduct Attitudes: Instrumental Algorithms for Action

As mentioned, conduct attitudes refer to the concrete actions and reaction patterns created by internalized rules and social norms. They are less flexible than relational or perceptual attitudes because they are often institutionalized through repeated social learning and are closely related to role expectations (eg, as a professional, parent, or citizen).

In our model, conduct attitudes are organized within internalized subgroups corresponding to different life roles.

When one's actions are inconsistent with one's underlying emotional or cognitive conduct attitudes—for example, when a person is forced by external pressures to behave in ways that conflict with deeply held personal beliefs [behavioral, emotional, or cognitive]—cognitive dissonance may manifest.

The dissonance, in turn, may trigger processes of attitude change or reinterpretation aimed at re-establishing internal consistency.

Integration and reduction of dissonance

The dynamic interrelationships between these sets of attitudes [expressed by key figures and leaders in the internalized groups and especially in the internalized board] are central to understanding how cognitive dissonance develops and is resolved.

When relational, perceptual, and conduct attitudes are coordinated, the self experiences a coherent sense of identity and consistency.

However, when an external influence or internal conflict causes a mismatch (eg, an external authoritative demand that conflicts with an internal schema of equality), dissonance occurs.

Festinger's theory (1957) suggests that such dissonance creates psychological discomfort, which the individual is motivated to reduce either by changing one or more of the sets of attitudes following changes in the internalized groups mainly in the internalized board and its subgroups but also in the other two internalized groups [the enemies’ group and the self-representation group] or by reinterpreting the conflicting information.

These attitude changes are related to the changes of the hierarchical positions of the leader selves in the corresponding subgroups. The leader self that overrides the previously hierarchically higher positioned leader self (or selves) will dictate its attitudes from now on.

Implications of the aforementioned for theory and research

By delineating attitudes into relational, perceptual, and conduct domains, the extended self model provides a richer framework for understanding cognitive dissonance. He emphasizes the possibility that dissonance may not only result from one contradictory belief or behavior, but may result from complex interrelationships of internalized positions in groups and subgroups of the internalized self.

Future research should explore the neurobiological and developmental correlates of these perceptual systems and investigate how changes in the relative strength or flexibility of these attitudes affect an individual's ability to resolve dissonance under social, political, or other pressure.

Festinger (1957) argued that cognitive dissonance occurs when people experience inconsistencies between their beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors. In the context of the proposed self-model, the dissonance may stem from:

External-internal value conflict: Think of a person whose world is based on internalized egalitarian values, and believes in equality and freedom of expression, but lives under a dictatorial regime that enforces strict conformity. Here, the external imposition of repressive norms forces conflict within the internal board.

The internal leader (who may initially represent a more egalitarian position) may gradually be replaced by an internalized image representing the authoritarian regime, as a mechanism to reduce dissonance.

Role-based mismatch: As mentioned, people fulfill multiple social roles (eg, professional role, family member, citizen). Each position is associated with its own subgroup within the internal board.

When new external or situational pressures demand behavior that contradicts the role-specific attitudes, dissonance can occur. For example, a teacher in a rigorous academic setting may experience internal conflict when his personal teaching philosophy clashes with institutional expectations, causing a reorganization of internal character representations to alleviate the discomfort.

The proposed self-model suggests that the dissonance is not just a passing cognitive state, but reflects a deeper struggle within a multi-layered internalized system. In some cases, the reduction of dissonance may involve the gradual integration of characters with external values within the internal board – in fact, a change in the hierarchy of the internalized characters’ representations.

In more extreme situations, such as life-threatening or traumatic circumstances, a temporary reorganization of the board may occur to prioritize survival over previously accepted positions.

Implications for future research on the integration of a complex model of the self with cognitive dissonance theory opens several avenues for empirical investigation. The researchers will be able to examine:

A] The dynamics of the inner board and the enemies’ group in people undergoing social or political pressure.

B] changes over time in the composition of internalized groups in response to dissonant life events and how these changes mediate behavioral outcomes.

C] Neurobiological correlates of these two.

We will conclude that it is possible and cognitive dissonance – as formulated by Festinger (Festinger, 1957) – can be [in part] reinterpreted fruitfully within a proposed multi-level self-model. This integrative approach we believe provides a richer framework for understanding how internalized character representations, social roles, and external pressures interact to produce the psychological discomfort of dissonance.

By viewing the self as a dynamic constellation of internalized subsystems interacting with the environment, we can perhaps better appreciate the complex processes underlying attitude change and adaptive behavior.

References

Festinger, Leon (1957). Cognitive dissonance theory. Stanford University Press.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Harmon-Jones, A. and Mills, J. (1999). Cognitive dissonance: Advances in central theory in social psychology. American Psychological Association.

Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. (Eds.). (1999). Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10318-000

That's it for now,

yours,

Dr. Igor Salganik and Prof. Joseph Levine

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Leave a comment