Conversation 71: Dissociative identity disorder in the light of our model of the "Self"

Hello to our readers,

Dissociative Identity Disorder, which was previously known as "Multiple Personality Disorder", is one of the most controversial topics in psychiatry and psychology. In recent years, there has been an increase in awareness of complex dissociation situations, along with an in-depth discussion of the validity of the disorder, its prevalence and how to treat it.

In this article we will examine dissociative identity disorder through a theoretical model for the "Self" which consists of three main components: (1) the "primary self" (2) the "directorate of internalized characters", and (3) the "internalized enemies’ group ".

We will also discuss therapeutic options derived from the model, referring to the individual sensitivity channels, to the influence of positive (mostly within the “directorate of characters”) and negative internalized figures (enemies) on the mental structure, and to the role of the inner leader in the board of internalized figures in the rehabilitation process.

AI-assisted illustration of the dissociative identity disorder

Dissociative identity disorder is defined as a mental condition in which two or more identities exist in the same person, where each identity is characterized by a different self-concept, behavior style, and even different memories (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). In many cases, there are significant gaps in the autobiographical memory, feelings of disconnection (derealization/depersonalization) and loss of time (Putnam, 1989).

Various studies indicate that dissociative identity disorder often develops as a response to complex or persistent trauma in childhood, such as physical, emotional or sexual abuse.

There are researchers and clinicians who question the reported prevalence rate of dissociative identity disorder and claim that many cases may be mistakenly labeled as a result of incorrect use of hypnotic techniques or overidentification. On the other hand, there is clinical and empirical evidence that quite a few patients with dissociative identity disorder are not properly diagnosed.

Separate identities (Alter Personalities): Each identity may have a different life history, a different age, unique features, and sometimes a different gender.

Dissociative fugue: periods in which a person "disappears" from his normal identity and behaves in a way that does not correspond to his basic personality, sometimes with no memory afterward.

Mutual lack of awareness between the identities: some identities may not be aware of the existence of other identities, or be only partially aware.

Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): flashbacks, nightmares, sensitivity to events that trigger traumatic memories, and more.

AI-assisted illustration of dissociative identity disorder

Here we will first give four examples from the medical and psychological literature that describe treatment for dissociative identity disorder (dissociative identity disorder:

Anna A. case

Source: Braun, B. G. (1986).

Case description: Anna, a 35-year-old woman, sought treatment with symptoms of dissociative fugues, depression, and anxiety. She reported "voices" expressing different opinions inside her head. During therapy, 12 different identities were identified, each of which represented repressed feelings or parts.

The course of treatment: Anna received psychotherapy that lasted for 5 years, during which a gradual integration of her identities was done through internal dialogue and trauma-focused sessions. EMDR therapy was used to process childhood traumas.

Result: After prolonged treatment, Anna was able to combine her identities into one consistent identity and lead a functional life.

Case Christine L.

Source: Putnam, F. W. (1989)

Case description: Christine, 28 years old, experienced long periods of lost time and found foreign objects in her home. In the treatment, 8 identities were revealed, each of which functioned independently and served as a defense mechanism.

Treatment course: psychotherapy with a psychodynamic approach and emotional stabilization exercises are used to provide security before processing the trauma.

Result: Christine learned to work with the identities and improve the ability to communicate between them, and was able to experience a significant improvement in the quality of her life.

Source: Fine, C. G. (1991):

Case description: Lisa, 25 years old, showed severe symptoms of dissociation, with identities talking to each other out loud. Severe traumas of sexual abuse at a young age were identified as the root of the problem.

Treatment course: step-by-step treatment, which began with a focus on emotional stabilization, providing tools for managing anxiety, and then processing the trauma using CBT techniques and gradual exposure.

Result: Lisa was able to reach a state of daily functioning and control the transition between identities.

Source: Ross, C. A. (1997)

Case description: Marie, 32 years old, was dealing with different identities that each "took command" during a crisis. She complained of memory loss and persistent anxiety.

The course of treatment: a long process that included trauma-focused psychotherapy, a combination of medication to balance moods, and guidance for developing an internal dialogue.

Result: Marie was able to integrate most of her identities and reach a sense of self-completeness.

These examples show how the treatment of dissociative identity disorder requires a delicate, multi-stage work, which includes a combination of psychological techniques, drugs, and often also unique psychotherapeutic techniques such as EMDR, all of which emphasize the importance of working with trauma and stabilizing the patient at the beginning of the process.

It is interesting that the topic is of interest to quite a few writers, below are a number of books written about characters that demonstrate the disorder:

Several popular and iconic writers of fiction have dealt with the topic of dissociative identity disorder or concepts close to the disorder, even if they did not explicitly describe it as such. The theme of multiple identities, dissociation and trauma has appeared a lot in literature in a metaphorical, psychological or fictional form. Here are some famous examples:

“Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde" by Robert Louis Stevenson (1886)

Summary: The book is about Dr. Jekyll, a respected and intellectual man, who creates a dark version of himself – Mr. Hyde – through a scientific experiment. His two identities struggle with each other, with each representing different sides of his soul.

The connection to dissociative identity disorder: the book is sometimes seen as a metaphor for dissociation or multiple identity personality disorder, especially in the struggle between good and evil within the human psyche.

“Sybil" by Flora Rheta Shreiber (1973)

Summary: The book is based on a true case of a woman named Shirley Mason, who was identified with 16 different identities as a result of severe childhood traumas.

Contribution: "Sybil" is one of the first books that brought the idea of dissociative identity disorder to public awareness. He described in detail the psychological treatment she underwent and the complexities of living with multiple identities.

"I, Claudia" by Christine Fulton and Frank Hubert (1980)

Summary: This book tells the story of a woman with multiple identities, who is dealing with severe childhood traumas. It is written in the first person, from the point of view of the different identities.

Uniqueness: the book focuses on the inner voices and the way they are organized in the character's life, and brings a reliable and exciting voice to her inner struggle.

"The Minds of Billy Milligan" by Daniel Keyes (1981)

Summary: This book is based on the true story of Billy Milligan, a man who was accused of serious crimes and claimed that they were committed by other identities inside him.

Contribution: Daniel Keys describes Milligan's psychological treatment process and the complexities of his split personality. The book provides insights into dissociative identity disorder and the trauma that caused the disorder.

"Fight Club" by Chuck Flank (1996)

Synopsis: The book follows the life of a nameless man who starts an underground fight club, while dealing with a charismatic and violent character named Tyler Darden.

The connection to dissociative identity disorder: the hero later discovers that the character of Tyler Darden is actually the result of a dissociative identity created as a result of stress and exhaustion. The book deals with the loss of control and the split soul of man.

"My Life" by Yann Martel (2001)

Summary: The story is about a boy who is in a lifeboat in the middle of the ocean with a Bengal tiger, and raises questions about identity, survival and truth.

Psychological interpretation: There are readers and critics who saw the story as a metaphor for dissociation, with the tiger representing another side of the hero's psyche.

1. Green, H. (1964). I never promised you a rose garden. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

2. Keyes, D. (1981). The minds of Billy Milligan. New York, NY: Random House.

3. Martel, Y. (2001). Life of Pi. Toronto, Canada: Knopf Canada.

4. Palahniuk, C. (1996). Fight club. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

5. Schreiber, F. R. (1973). Sybil. New York, NY: Warner Books.

6. Stevenson, R. L. (1886). Strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. London, England: Longmans, Green & Co.

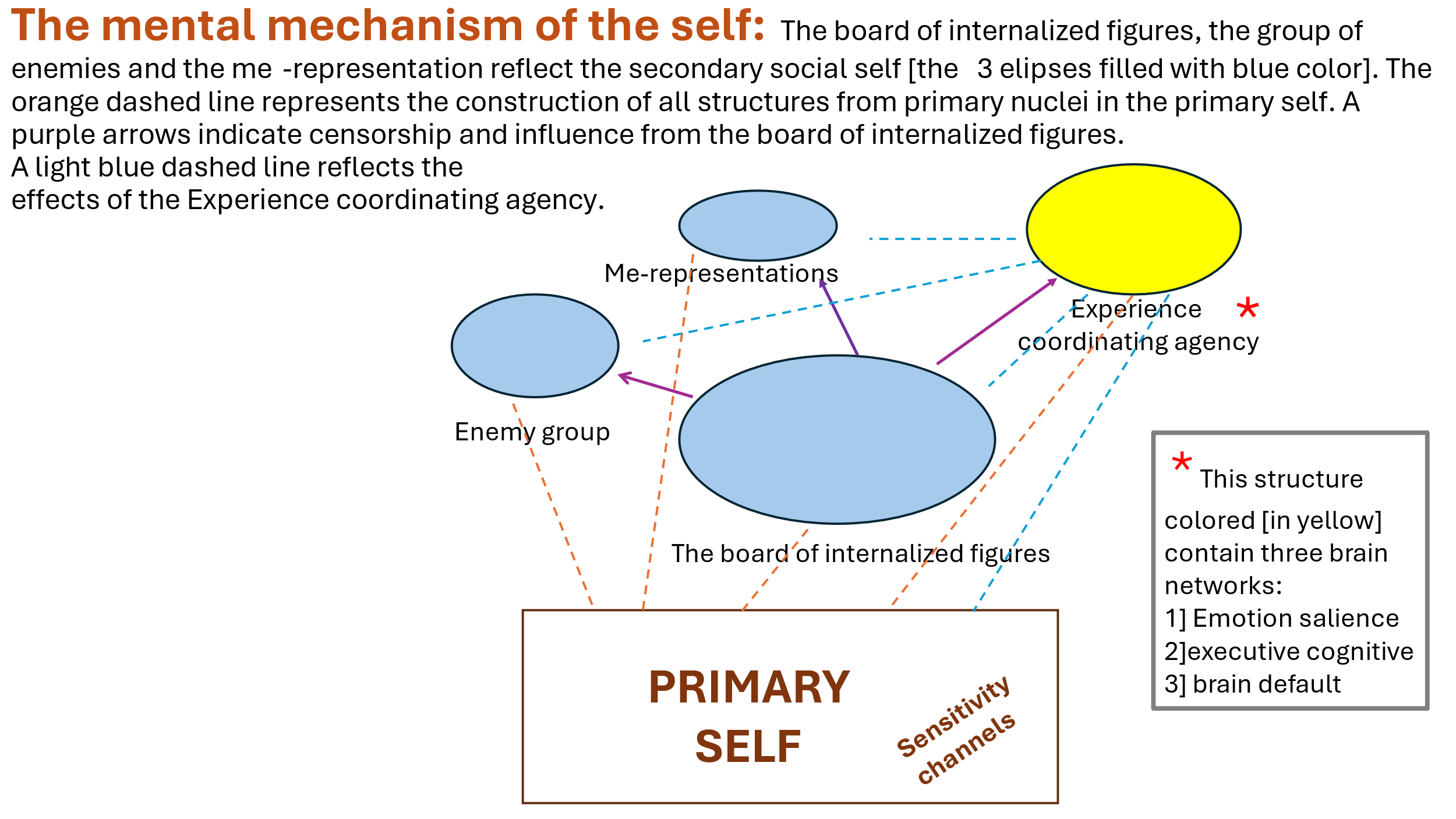

We will now move on to the "Self" model we are developing which includes the "primary self", the board of internalized characters, the enemies’ group and the self-representations.

The model assumes, among other things, four main components in the mental structure:

"The Primary Self" (biological predestined core)

"The Board of Internalized Characters"

"The Enemies’ Group"

Also, within the framework of the primary self, "individual sensitivity channels" (ISC) were defined that express the natural tendency of the person to react to external and internal stressors.

The model serves as a tool for understanding how different characters (with real origin or imaginary) "organize" within the human psyche, and how the relationships between them may explain situations of identity splitting such as dissociative identity disorder.

The Primary Self (biological predestined core)

Definition: The primary self is the basic "biological core", consisting of innate structures (instincts, temperament, emotional intelligence, etc.). This core develops gradually while interacting with the environment (for example, social learning, contact with caring figures) and may change due to trauma, illness, drug consumption, various life experiences, etc.

The individual sensitivity channels (ISC) include:

The status channel – sensitivity regarding one's social status and position.

The norms channel – sensitivity to changes in accepted norms and behaviors in one's environment.

The attachment channel – sensitivity in relation to the emotional connection with the other (parents, spouses, friends, etc.).

The threat channel – high sensitivity to sources of threat or danger.

The routine channel – sensitivity to changes in the daily routine.

The energy channel – sensitivity to a decrease in the level of physical and mental energy (for example, states of fatigue, burnout).

The proprioceptive channel – sensitivity to sensations arising from the body and sensory reception.

Mental health: the less extreme sensitivity the person shows in each of the channels, the more balanced the mental function. Hypersensitivity in one or more of the channels may indicate pathology.

Illustration of our "Self" model for mental life

We note that in cases of dissociative identity disorder, a particularly high sensitivity sometimes arises in the threat channel (4) and the attachment channel (3), due to experiences of harm or abandonment.

Board of Internalized Characters

The directory of internalized figures is a collection of "internal figures" or personal representations of significant people and/or subcultures, arranged in an internal hierarchy.

The term "board" is metaphorical, and its purpose is to illustrate the idea of an internal “directorate”, where certain figures have great influence and even leadership while other figures are more secondary.

There is usually a "leader figure" (or several leaders) at the top of the thigh, which is sometimes referred to as the "internal censor" or the "leader self". This figure has a major influence on the shaping of attitudes, feelings and behaviors.

These characters are internalized starting from childhood on and then throughout the whole life through interaction with parents, teachers, friends, and later also through exposure to books, movies and social events.

Sometimes, imaginary characters (such as literary or cinematic heroes) can be internalized and play a role.

When the board of directors is diverse (and not controlled by one exclusive figure), there is inner dialogue and cooperation, this indicates mental flexibility.

When there is only one character who dominates and even resembles a “dictator”, this may herald a mental disorder (for example, a personality disorder following a critical and rigid character who dictates all behaviors and attitudes).

In the case of dissociative identity disorder, it is possible for the board to be split into several internal sub-boards, each with its own leader, so that each sub-board creates a different "identity" that dominates separate parts of the wider board system.

In essence, there is a dissociation of the broad board before the start of the disorder. This may explain the extreme disparities in self-perception and memory: each identity may have its own sub-directorate, where a composition of internal figures and leaders operates and the fragmentation between the sub-directorates contributes to a possible lack of awareness of one identity over another.

The “internal enemies’ group”

This is a group of negative or threatening internalized figures, often formed following trauma or ongoing damage. These characters are not allowed to "fit in" with the regular board and exist in a separate mental space.

They may represent the offenders, the deep anxiety about them or the fear of repeated trauma.

This group has a survival function: from an evolutionary point of view, animals and humans "store" enemy figures to beware of them in the future.

However, in a situation of continuous trauma (such as childhood abuse), a pathology may develop in which the "enemy group" becomes stronger and tends to "attack" and penetrate the general board and causes continuous distress.

Difficulty moving between groups: In general, characters perceived as threatening do not "move" into the character board, but remain in the negative enemies’

group space. However, in acute stress situations, these figures may "seep into" consciousness in general and the wider board group in a specific manner and create emotional flooding, flashbacks or destructive actions following the creation of a negative identity or identities.

In dissociative identity disorder, there may be situations where one or more of the identities is actually identified with the "enemies’ group" – that is, actively embodies aggression or extreme fear.

When such an identity "comes to the stage", it can penetrate the boundary between it and the general board and create a sub-board that will represent a negative identity with introverted figures who were relatively passive in the broad board and will now support the positions of the internal leader arising from the enemies’ group that will influence in the direction of creating destructive behavior, suicidal thoughts or self-harm.

Under conditions of stress and trauma in childhood, the primary self (consisting, among other things, of mechanisms and memory stores and a variety of emotional and cognitive abilities) "uses" the ability to dissociate among the memory stores and a variety of other abilities.

And instead of a unified primary self, different parts are built that are designed to contain difficult aspects of the experience.

In addition, the threat channel becomes particularly active, and as a result the child may develop an identity that is an expert in "survival" or "disappearance" (for example, an identity that experiences the trauma directly).

Even the attachment channel may be strained, and in order to deal with the difficult feelings of betrayal or abandonment, a different identity develops that will maintain a more normative function vis-à-vis the environment.

In ongoing trauma situations, the usual broad "board" (consisting of internalizations of parents, teachers and influential figures) fails to cope with the load.

Secondary characters or usually "mute characters" may take the lead. It's actually like an "internal revolution", in which several separate sets of characters are created – each trying to manage reality from its own point of view.

In situations of dissociative identity disorder, we may have a compartmentalization where several subdirectorates are obtained, each of which experienced as a distinct identity.

The penetration of the "enemies’ group" into the forefront of consciousness: the enemy group, which under normal circumstances would have remained peripheral, may surface and radically affect personal identity. An aggressive identity may appear: which may adopt hostile behavior, reminiscent of the offender.

An identity representing chronic fear and anxiety may also surface. Basically, anxiety breaks through a character from the group of enemies to the internalized directorate board with an impairment of the ability to bond and the desire to develop intimate relationships.

According to our model, there is a "collection of ego representations" that refers to different ages and aspects of an individual's life (child, teenager, adult, body, etc.).

When a dissociative identity disorder develops, some of the representations of the past self may surface and create a subdirectorate in which some of the characters of the broad board will be recruited and we will get an identity that operates from the perspective of a child or adolescent or an adult.

Thus, a situation can appear where one of the identities is a "5-year-old girl", who expresses fear and anxiety in a childish manner, while another identity is an "adult" who functions roughly in everyday life.

Note that there is usually a flow from the character board mostly and much less [in a normative case] from the enemies’ group to the current self representation. In dissociative identity disorder, the boundaries between the internalized groups [the board of directors group, the enemies’ group, the group of self representations] are weakened and, as mentioned, there is an intrusion of character representations between the groups. In addition, the Board of Directors is not stable, and neither are the other groups, and there is a tendency to split within the groups and create sub-directorates and possibly subgroups when each constitutes a different identity.

It is possible that the fuel for such a split is a strong [negative] emotion associated with early trauma and that internal triggers or triggers in the external environment that may activate one or another strong negative emotion contribute to dissociation and the creation of subgroups and subgroups representing different identities. Such fragmentation is probably needed as a kind of defense mechanism to protect from the intense emotional flooding [intense fear, paralyzing anxiety and more].

Treatment of dissociative identity disorder from the perspective of our "self model" in RGFT therapy

General principles for treatment:

The treatment of dissociative identity disorder consists of long-term psychotherapy combined with trauma processing techniques. The ultimate goal is to create an integration process or at least cooperation and connection between the identities.

Behavioral and emotional stabilization: in the first stage, it is important to stabilize the patient emotionally, the intention is to provide tools for regulating anxiety, preventing self-harm and dealing with everyday stressful situations (for example, mindfulness training, biofeedback, self-soothing techniques).

Processing the trauma: a critical phase during which the patient, accompanied by the therapist, gradually explores and processes the memories of the trauma.

EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) is sometimes used to reduce the emotional intensity of the traumatic memories.

Reorganization of the board and the internalized groups [RGFT treatment, see previous articles on this treatment]: in a more advanced stage, the therapist helps the patient identify the different characters, the role they play, and create a dialogue between them.

Reducing the dominance of the "enemy group": knowing the threatening characters and creating a process of gradual "containment" or "neutralization" of them.

In some cases, it is even possible to transfer some of the characters from the group of enemies to the board, when a renewed understanding of their role emerges.

Link between the self-representations: The therapist helps to "connect" a connecting thread between the different self-representations (child, teenager, adult) [if they appear as different identities in the disorder] in a historical sequence so that a developmental sequence is created up to the present self-representation.

Practices such as the "empty chair" technique (which comes from the Gestalt world and is applied in the RGFT approach) allow the patient to speak on behalf of one of his parts, while another part "listens", and thus begins a process of building mutual awareness and integration.

Practical applications of the model in therapy

Character mapping: in the assessment phase, the therapist and patient together build a "map" of the various characters – whether they are part of the board of directors or the group of enemies or self-representations.

Each character is identified by name, approximate age, emotional role and their main attitudes. It is not simple. Reports from close people and others who accompanied the characters can be used. In photographs and video recordings of the various characters if they appeared during the treatment and were video-recorded or were video-recorded by other people. You can also use evidence of behaviors and actions such as documents, the appearance of various objects, and more.

It is useful to start with the figure of the leader or the main leaders before the disturbance breaks out and let them lead towards the integration of the identities and the construction of a set of groups, especially a board of broad, stable and normative internal figures and a separated group of enemies and different representations of the self separated in a historical sequence with a single contemporary representation of the self adapted to the age and background of the subject.

Identifying the dominant relevant sensitivity channels: it is necessary to examine in which channel or channels there is hypersensitivity (for example, the channel of the threat or attachment). This will help the patient understand how external stimuli may activate a particular identity.

Defining a healthy "inner leader": within the therapeutic process, an attempt is made to develop or strengthen a "leader figure" capable of coordinating all the inner figures. This is not some kind of internal dictatorship but "participatory leadership", which allows every part of the soul to be expressed without harming the overall integrity.

Gradual exposure of the enemy figures: The therapist may invite an "enemy figure" [who is the leader of a subgroup representing one of the identities] for a conversation using the hot chair method, while creating a safe space.

Sometimes it turns out that the "enemy figure" protects the patient from even greater pain, and awareness of this may reduce the intensity of the conflict. Sometimes a different understanding of the enemy character can advance his inclusion in the board of characters towards integration.

Sometimes the combination of this leading enemy figure with other enemy figures and the creation of a distinct enemy group with a clear boundary from the board [whereas the board will go on expanding while adding a variety of identities to it towards integration] can be helpful.

In addition, creating a clear boundary from the representations of the self [which will undergo a reorganization in historical order with an emphasis on the representation of one current self] can provide useful.

Supportive drugs: There is no specific drug for dissociative identity disorder, but antidepressants (SSRIs), anti-anxiety drugs or mood stabilizers are sometimes used, with the aim of lowering the levels of intense emotion such as anxiety and depression levels that can exacerbate the dissociation.

Additional points of interest

Beyond the main summaries, there are several additional insights or points:

The perception of the "self" as a continuous continuum versus the illusion of continuity:

Philosophical and Eastern approaches (e.g. Buddhism) suggest that the "self" is not of one piece to begin with.

Dissociative identity disorder is an extreme illustration of a situation that exists at some level in everyone: we are all made up of "parts" that conduct an internal dialogue.

Influence of gender on the dissociative experience

Clinical studies show that sometimes some identities can be of a different gender. Gender transition is an expression of the depth of the split and the difficulty of the self to form a uniform gender identity.

"Holes" in memory: dissociative lulls and loss of time (Lost Time) are a key sign for identifying dissociative identity disorder. The patient may discover objects or products of actions that he does not remember performing.

Suggestiveness as an expression of boundary permeability:

Some believe that people with more "permeable" boundaries (boundaries between conscious and unconscious, or between the parts of the self and the primary between the internalized groups) tend to develop dissociation and even dissociative identity disorder. Thus, high suggestibility may be a mediating factor.

Professionals who do not know the disorder in depth, may mistakenly interpret expressions of dissociation as projective pretense, psychosis or borderline personality disorder. Thus, a correct diagnosis is sometimes avoided, and the patient is left without an appropriate therapeutic response.

It seems that in Western countries (USA, Canada, Europe) there is more awareness and diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder. In traditional societies, "splitting of identity" may be interpreted as an experience of possession or "spirits", and therefore receive traditional-ritual treatment and not necessarily psychotherapy.

Dynamics of the integration process

Integration is not necessarily a "full merger" of all identities into one. There are approaches that talk about "cooperation" between identities while preserving plurality, but with less conflict and higher memory accessibility.

The effect of traumatic events on the creation of an "enemy group":

We have hypothesized that continuous trauma has a role in the creation of a strong enemy group that separates from the board, which is on the one hand a kind of defensive mechanism, but on the other hand may penetrate following a strong negative emotion or triggers that arouse it into the board and the internalized characters even into the self-representations , thus causing dissociation and the emergence of an identity or identities with negative characteristics.

Passing identity as a "resource capture" mechanism:

It is also possible to see in some of the sharp transitions between identities an (unconscious) attempt of the soul to recruit additional abilities, tools and powers that were not accessible within the normal personality.

Need for systematic strengthening of the "self" and its parts.

In dedicated treatment, emphasis is placed on strengthening the initial self, and on the integration of the groups that make up the self, which may have been affected by trauma before the development of the disorder. This includes restoring the board, separating the enemy group and reducing its influence, and restoring the current self-representation.

Finally, dissociative identity disorder continues to provoke diverse discussions in the clinical and academic community: from debates about its very existence and prevalence, to the questions we face about the essence of the "self" and its parts, including the internalized groups and the boundaries between them.

The model described in this article – which combines the idea of the "primary self", the "directorate of internalized characters", the "enemies’ group" and the "self-representationsf" – provides a unified theoretical framework for understanding the complex internal dynamics in dissociative identity disorder.

Through the model, we hope that it is possible to explain how early trauma may cause splits in identity, and how some identities are related to previously internalized positive characters (in the directorate of internalized characters) and others are related to experiences from threatening characters (in the enemies’ group).

On the therapeutic level, focusing on stabilization, trauma processing and internal dialogue between the characters [in RGFT therapy] allows promoting integration or at least cooperation between the different parts.

Deepening the research in this model may provide more practical insights into the treatment of dissociative identity disorder and also serve to understand a wide range of dissociative phenomena.

List of sources on dissociative identity disorder and the clinical model

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Braun, B. G. (1986). Issues in the psychotherapy of multiple personality disorder. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 29(2), 119–128.

- Brand, B. L., Loewenstein, R. J., & Spiegel, D. (2016). Dispelling myths about dissociative identity disorder treatment: An empirically based approach. Psychiatry Research, 229(3), 384–394.

- Fine, C. G. (1991). Treatment stabilization and crisis management in the dissociative disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 14(3), 661–675.

- Kluft, R. P. (1993). Clinical presentations of multiple personality disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 16(4), 633–647.

- Lynn, S. J., Krage, M. & Rhue, J. W. (2010). Hypnosis and the altered state debate: Something more or nothing more? Contemporary Hypnosis, 27(1), 19–31.

- Putnam, F. W. (1989). Diagnosis and treatment of multiple personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

• Ross, C. A. (1997). Dissociative identity disorder: Diagnosis, clinical features, and treatment. New York, NY: Wiley.

• Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Literary and popular sources (to illustrate the idea of split identity)

• Keyes, D. (1981). The minds of Billy Milligan. New York, NY: Random House.

• Martel, Y. (2001). Life of Pi. Toronto, Canada: Knopf Canada.

• Palahniuk, C. (1996). Fight Club. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

• Schreiber, F. R. (1973). Sybil. New York, NY: Warner Books.

Additional theoretical sources

• Perls, F. S., Hefferline, R. F., & Goodman, P. (1951). Gestalt therapy: Excitement and growth in the human personality. New York, NY: Julian Press.

Last things

Understanding dissociative identity disorder requires a multidimensional observation: biological, psychological and socio-cultural.

The model of the "self" that includes the "primary self", the "directory of internalized figures", the " enemies’ group" and the "self-representations" offers in our opinion a rich road map for therapists and researchers alike, and illuminates the ways in which the treatment of internal figures, traumatic memories and innate sensitivity channels can serve therapeutic purposes.

We suggest that all these together form the complex clinic of dissociative identity disorder. The treatment of patients with dissociative identity disorder often requires creativity, patience and an empathetic approach, while understanding that any identity – even if it seems threatening or destructive – may originally be intended to protect the individual.

Combining different treatment approaches including RGFT may lead to positive results and allow the patient to live a fuller and healthier life on a mental and interpersonal level.

That’s for now,

Yours,

Dr. Igor Salganik and Prof. Joseph Levine

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Leave a comment