Conversation 74: Procrastination: The Biological and Psychological Mechanisms Underlying It, Along with Its Reflection According to the Model We Develop for the "Self"

Hello to our readers,

Procrastination is generally defined as the voluntary delay of a planned course of action despite the expectation that the situation will be worse because of the delay. In other words, people knowingly postpone or delay necessary tasks to their detriment.

This behavior is extremely common—by some estimates, about 15-20% of adults (and about half of students) are chronic procrastinators who experience frequent and problematic delays in important tasks. Procrastination is not a trivial habit; it is considered a “common and harmful form of self-regulatory failure.”

Chronic procrastination is associated with a variety of negative outcomes, including poorer academic or work performance, higher stress, and reduced psychological well-being. Studies have found that people who regularly procrastinate report greater anxiety, along with depression, and higher feelings of distress and hopelessness compared to those who do not procrastinate. Given the widespread prevalence and harm of procrastination, understanding the mechanisms underlying the phenomenon is of great interest.

AI-assisted illustration of procrastination

Historically, procrastination has been viewed primarily as a psychological phenomenon—essentially a failure of self-regulation or the inability to resist immediate temptations. Indeed, many psychological factors have been identified as contributing to procrastination, such as task avoidance, fear of failure, low self-efficacy, impulsivity, and poor organization.

However, in recent years, researchers have also begun to investigate the biological and neuropsychological basis of procrastination. Findings from genetics and neuroscience suggest that procrastination may have measurable biological components—for example, inherited personality traits and specific brain circuits involved in our tendency to procrastinate.

Below, we provide an overview of the mechanisms of procrastination from both a biological and psychological perspective. We first examine the biological mechanisms of procrastination, including genetic predispositions and neural processes that contribute to procrastination behavior. We then discuss psychological mechanisms, such as cognitive, emotional, and personality factors that drive the habit of procrastination.

Finally, in the discussion, we will integrate these perspectives to show how biological and psychological factors interact to contribute to procrastination, and we will evaluate evidence-based interventions that leverage these insights. Finally, the conclusion summarizes key points and highlights possible strategies for reducing procrastination based on the mechanisms discussed. From here, we will move on to understanding procrastination in light of the model of the “self” that we are developing.

Genetic Predisposition

Evidence from behavioral genetics suggests that procrastination is not solely a result of environment or personal choice, but has a significant hereditary component. A twin study found that approximately 46% of the variance in chronic procrastination is explained by genetic influences (with a similar heritability to impulsivity = ~49%).

Notably, one study showed that procrastination and impulsivity share a complete genetic overlap—in fact, the same genetic factors that make a person impulsive also make them prone to procrastination. In other words, at a genetic level, procrastination appears to be a byproduct of impulsivity.

From an evolutionary perspective, researchers have hypothesized that impulsivity (the tendency to seek immediate rewards) may have been adaptive in uncertain environments, and that procrastination may be an evolutionary byproduct of this trait. Consistent with this idea, genetic influences on a person's ability to manage goals (goal management ability) account for much of the shared genetic basis of procrastination and impulsivity.

People who have inherited traits such as poor self-control or high impulsivity are biologically predisposed to put off tasks, especially when temptations or distractions are present.

Beyond twin studies, molecular genetics research has begun to identify specific genes and neurochemical pathways that may be involved.

Because self-regulation of behavior is largely influenced by neurotransmitters like dopamine (which controls reward and motivation), researchers have examined dopaminergic genes for links to procrastination. For example, one study found that variation in the gene encoding tyrosine hydroxylase (an enzyme that regulates dopamine synthesis) was associated with differences in procrastination tendencies, at least among study participants.

Although such findings are preliminary, they suggest that the efficiency of dopamine signaling—which influences the strength of the tendency to achieve goals versus seek immediate gratification—may be one biological factor influencing procrastination.

It is worth noting that the relationship between biology and behavior is complex: recent research suggests that genetic, anatomical, and functional differences can influence the trait of procrastination independently, with no single pathway fully determining behavior.

In summary, there is a significant genetic and biochemical basis for procrastination, particularly as it overlaps with the biology of impulsivity and reward seeking.

Neural Circuits and Brain Mechanisms

Neuroscience research has shed light on how certain structures and circuits in the brain may cause people to procrastinate. Procrastination can be thought of as an imbalance between our brain's "regular/impulsive" and "goal-directed/executive" systems.

The limbic system—an evolutionarily older area of the brain involved in emotion and immediate reward—often drives a person to seek comfort or avoid stress now, while the prefrontal cortex—a newer area responsible for long-term planning and self-control—allows us to work toward future goals.

Procrastination can occur when the limbic system’s desire for immediate mood correction overrides the prefrontal cortex’s guidance for strenuous tasks. In other words, neuroscientists describe it as a constant battle in the brain: the limbic system demands immediate gratification or escape from unpleasant tasks, while the weaker prefrontal cortex struggles to keep us on track.

In effect, the "present self" (controlled by limbic impulses) wins over the "future self" that will benefit from completing tasks – essentially a kind of struggle or neural war biased towards short-term reward.

Brain imaging studies provide tangible evidence of this emotional-executive imbalance in chronic procrastinators. Researchers used MRI [magnetic resonance imaging] to compare brain structure and connectivity in people with high versus low action control (the ability to initiate and complete actions quickly).

The study found that people who had difficulty with action control – in effect, frequent procrastinators – had larger amygdala volume and weaker functional connectivity between the amygdala and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dACC).

The amygdala is a central limbic region that generates feelings of fear and evaluates potential negative consequences (e.g., anxiety or terror associated with a daunting task), while the anterior cingulate cortex is involved in executive functions such as decision-making and using this emotional information to choose a course of action.

In procrastinators, an overactive or enlarged amygdala may produce stronger “alarm signals” about a task (e.g., perceiving it as threatening, overwhelming, or terribly boring), while weaker connections to the frontal control center mean that these signals are regulated and moderated less effectively.

This neural profile supports the idea that procrastination is associated with higher sensitivity to negative emotions combined with a reduced ability to override these emotions and initiate action.

Other brain imaging studies similarly suggest that procrastination is linked to differences in the frontal circuits responsible for cognitive control: for example, people who are more sensitive to punishment (negative outcomes) show greater procrastination, mediated by weaker connectivity between the caudate nucleus (a region involved in habit formation) and the prefrontal cortex.

Such findings highlight that procrastination has identifiable neural correlates – essentially, a brain that is wired to prioritize immediate comfort or avoid threats can undermine a person's intentions to work on long-term goals.

Another biological aspect of procrastination is its interaction with stress and the hormone cortisol. The act of procrastination often provides temporary relief (reducing stress in the short term by avoiding the task), but as deadlines approach, stress levels rise dramatically.

This can create a feedback loop in which procrastinators chronically expose themselves to high stress, which in turn can impair memory, executive function, and self-control through elevated cortisol levels affecting the prefrontal cortex.

Over time, this pattern may biologically reinforce procrastination by conditioning the brain to seek immediate stress reduction by avoiding tasks whenever a daunting task triggers anxiety.

In conclusion, from a biological perspective, procrastination involves a genetic predisposition and neurobiological dynamics—a kind of “fight” between brain systems—that bias the individual toward short-term relief at the cost of long-term gains. Identifying these biological mechanisms helps explain why the decision not to procrastinate can be difficult, as deep-rooted neural processes play a role.

AI-assisted illustration of procrastination

Psychological mechanisms

While biology sets the stage, the decision to procrastinate in any given situation is heavily influenced by psychological factors. Procrastination is often described as a complex interaction of cognitive, emotional, and motivational processes. Below, we describe a number of key psychological mechanisms identified by research:

Cognitive and Motivational Factors

Impulsivity and Choosing Short-Term Gratifications: At its core, procrastination represents a breakdown in self-control—choosing short-term gratification (or relief) over long-term benefits. Highly impulsive people tend to discount future rewards too significantly; that is, a reward or outcome loses its perceived value if it is delayed.

This temporal discounting causes procrastinators to prefer immediate, pleasant or convenient distractions over tasks that pay off later. That is, even if a person rationally knows that completing a project is the best thing to do, the present self may underestimate the value of future rewards (such as a good grade or a raise) relative to the immediate rewards of, say, watching a funny video or simply avoiding stress.

This is consistent with the temporal motivation theory, an integrative framework that proposes that motivation = (expectancy × value) / (impulsivity × delay). Procrastination becomes more likely when expectancy (confidence in success) or value (attractiveness of the task) are low, or when impulsivity and delay are high. For example, if a task is abstract, distant, or lacking in intrinsic pleasure, and the person is impulsive, their motivation to start the task will be much lower until the deadline becomes imminent.

This (often unconscious) cognitive calculation contributes to the common experience of procrastinators "waiting for the last minute" when the immediacy of the deadline finally increases the motivational significance of the task.

Task resistance and perfectionism: People are more likely to procrastinate on tasks that they perceive as daunting, difficult, or emotionally painful.

Extensive meta-analytic evidence suggests that task aversion (dislike of the task) is a strong predictor of procrastination. If working on a task is likely to elicit boredom, frustration, or anxiety, procrastination provides a temporary escape from these negative emotions. Relatedly, fear of failure can make tasks feel daunting; people who fear poor performance may procrastinate as a strategy for this self-limitation.

By putting off work, procrastinators can maintain their self-esteem with an “excuse” if the result is not good (“I only failed because I rushed at the end”).

Paradoxically, perfectionism – setting unrealistically high standards – can also lead to procrastination when people feel paralyzed by the fear that their work will not meet expectations. In such cases, starting the task triggers anxiety about making mistakes, so the person copes by avoiding the task altogether. Therefore, both low task attraction and performance anxiety contribute to procrastination by reducing the person's immediate willingness to engage.

AI- assisted illustration of procrastination

Self-efficacy and decision paralysis: Cognitive assessments of one’s abilities also play a role. Research suggests that low self-efficacy – doubting one’s ability to successfully complete a task – is linked to procrastination. If people lack confidence that their efforts will lead to success, they are more likely to put off action (“What if I’m doing it wrong?” or “I’m not sure how to do it”).

Procrastination can therefore function as an avoidance of expected failure or confusion. In addition, procrastinators often struggle with making decisions (a phenomenon known as decision procrastination). When faced with choices (e.g., how to approach a complex project), they may overthink and become paralyzed by indecision, leading to delays.

This is linked to a tendency to overthink and perfectionism – an inability to settle for a “good enough” plan can result in no plan at all. Over time, repeated procrastination can further erode self-efficacy, creating a vicious cycle: the person remembers past delays and crises, feels even less confident in tackling new tasks on time, and is therefore tempted to procrastinate again.

Short-term mood correction: A prominent psychological view of procrastination is that it is driven by emotional regulation needs. Researchers have shown that students may procrastinate to temporarily improve their mood, even if it hurts later performance. Others have described procrastination as "the primacy of short-term mood correction over long-term goals."

According to this view, when faced with a daunting task that causes stress or boredom, procrastinators turn to more pleasant activities (or simply postpone the task) as a way to immediately lift their mood or relieve discomfort. This is essentially an emotion-focused coping strategy: by avoiding the task, they also avoid the negative emotions associated with it—at least for the time being.

Unfortunately, the relief is temporary; the task still lingers, often leading to increased guilt and stress later. Empirical research supports this mechanism: procrastinators tend to report higher stress and negative emotions after procrastination, and chronic procrastination is associated with difficulties with emotional regulation.

In one study, college students who procrastinated had higher levels of depression and anxiety, suggesting that they may use avoidance to cope with these unpleasant feelings. Over time, relying on procrastination to fix their mood backfires by piling up problems—missing deadlines, rushing work, and feelings of failure—that in turn fuel more negative mood. This cycle helps explain why procrastination often hurts well-being: The short-term emotional gain outweighs the long-term emotional cost.

Stress and arousal management: Another emotional aspect is how procrastinators manage arousal. Some people claim to “work best under pressure” and intentionally put off tasks to get a last-minute adrenaline rush. These arousal procrastinators are essentially using procrastination to put themselves in a high-stress, arousing situation. However, studies generally find that procrastinators do not produce higher quality work under pressure; it is more of a rationalization than a functional strategy.

In many cases, procrastinators misregulate their stress: either they procrastinate to avoid stress (until it becomes extreme), or they seek the stimulation of an approaching deadline but slip into harmful stress.

Chronic procrastination has been linked to higher stress levels and poorer mental health, suggesting that procrastination is an ineffective long-term strategy for managing emotional arousal. Furthermore, high stress reactivity (e.g., feeling overwhelmed easily) can increase procrastination by making people more likely to “freeze” or escape from a demanding situation.

Therefore, emotional reactivity and dysregulation are central to the procrastination puzzle—procrastinators often prefer to feel better now at the expense of their future emotional state.

Personality Traits and Attitudes: Several broad personality traits cause people to procrastinate by influencing their typical thoughts and feelings. Low conscientiousness is the trait most strongly associated with procrastination. People with low conscientiousness tend to be disorganized, easily distracted, and have poor self-discipline, which naturally leads to procrastination.

High neuroticism (a tendency to experience negative emotions) may seem like an obvious contributor, but meta-analyses show that neuroticism is only weakly related to procrastination, but overlaps with anxiety and impulsivity. On the other hand, certain attitudes and thinking styles do increase the risk of procrastination.

For example, rebelliousness or low motivation for tasks can manifest itself in procrastination on tasks that a person abhors—essentially a passive-aggressive form of resistance. Similarly, an optimistic bias (“I’ll have time later” or “I work best under pressure”) can lead people to underestimate the consequences of procrastination. In summary, the psychological profile of procrastination includes low self-control, a desire to avoid negative emotions, and often rationalizations that preserve the behavior.

These cognitive-emotional factors work in tandem with the biological predispositions described earlier, ultimately producing the observed procrastination behavior.

Discussion

Procrastination arises from the dynamic interplay between biological and psychological mechanisms. This suggests that procrastination is not simply a character flaw or a matter of time management, but a complex behavior with roots in our brains and our minds.

Below we will integrate the biological and psychological perspectives and discuss how this integrated understanding can aid in interventions to reduce procrastination.

Integrating Biological and Psychological Perspectives

A useful way to conceptualize procrastination is as a breakdown in self-regulation involving multiple levels of causality. At a biological level, a person may have an innate tendency toward impulsivity or increased sensitivity to stress—for example, due to genetic factors or neurobiological wiring. This can manifest psychologically as difficulty tolerating uncomfortable emotions and resisting temptations.

The "struggle" between the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex mentioned earlier is actually a biological description of what psychologically can be described as a battle between a person's emotional impulses ("I'd rather feel good now") and their rational intentions ("I need to do this for my future").

When the limbic (emotional) side is stronger, the person experiences strong urges to run away or postpone the task, often justifying the delay with thoughts such as “I’ll feel better tomorrow” or “I work better when I’m in the right mood.”

These justifications align with the mood-correction mechanism – the brain quickly learns that not completing the task provides immediate relief from anxiety or frustration, reinforcing the habit of procrastination (through negative reinforcement, in behavioral terms).

From a psychological perspective, an individual's beliefs and traits can either moderate or exacerbate these biological tendencies. For example, someone who is genetically predisposed to impulsivity may still avoid procrastination if they have developed strong conscientious habits and positive self-efficacy beliefs.

In contrast, a person with relatively balanced biology may still fall into procrastination if they have learned poor coping strategies (e.g., always escaping stress by avoiding it) or have distorted cognitions (e.g., perfectionistic thinking, fear of failure).

In many cases, procrastination perpetuates itself through feedback loops: delaying work leads to hasty and lower-quality results, which can damage a person's self-esteem or success, which produces negative emotions that feed back into further procrastination.

Over time, both the brain and behavior can change—chronic procrastinators may instill a strengthening of neural pathways for seeking distraction and anxiety relief, effectively habituating procrastination at a biological level.

This highlights the importance of treating procrastination on multiple fronts. Importantly, recognizing the biological factors behind procrastination can foster self-compassion and more effective strategies.

Rather than seeing procrastinators as simply “lazy,” we understand that there may be innate differences in how strongly a person’s reward system craves immediate gratification or how strongly the threat system (amygdala) responds to a task. This doesn’t excuse the behavior, but it does suggest that overcoming procrastination may require ways to circumvent our natural tendencies.

Psychological factors also remind us that procrastination is modifiable—it is essentially a learned behavior pattern that can be unlearned or replaced with better habits. Indeed, studies have shown that interventions can significantly reduce procrastination, suggesting that even if a person has a biological predisposition, the behavior is not unchangeable.

The combination of perspectives can be summarized as follows: Biology creates vulnerability that leads to procrastination (through genes, brain systems, and personal temperament), and psychology shapes how this vulnerability manifests itself in specific situations (through learned thoughts, feelings, and behaviors).

Strategies and Interventions to Reduce Risk

Understanding procrastination opens up a variety of intervention strategies. On the psychological side, many approaches have shown promise in reducing procrastination:

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) directly targets the unhelpful thoughts and behaviors associated with procrastination. For example, a procrastinator may learn to challenge irrational beliefs (“I have to be in the perfect mood to work” or “If I can’t do it perfectly, I shouldn’t do it at all”) and replace them with more adaptive thoughts (“I can make some progress now, even if it’s not perfect”).

Behavioral techniques focus on breaking down tasks into smaller, more manageable steps and committing to starting only for a short period of time. This leverages the idea that getting started is often the hardest part—once a person starts, anxiety often decreases and momentum builds. Empirical research supports the effectiveness of CBT: Randomized trials have found that CBT-based interventions produce moderate to large improvements in procrastination behavior relative to no treatment.

In practice, therapists help clients set specific goals, set deadlines, use diaries or to-do lists, and develop strategies for coping with setbacks. Over time, CBT can strengthen a person’s self-regulation skills, effectively “rewiring” some of the learned procrastination patterns.

Emotional regulation training: Because procrastination is often a way to cope with negative emotions, training people in healthier emotional regulation can be effective.

Techniques include mindfulness meditation, which has been shown to reduce stress reactivity and increase tolerance for unpleasant emotions. Mindfulness and relaxation exercises may help metaphorically “shrink the amygdala”—that is, reduce the power of anxiety triggers—and improve functional connectivity in the brain’s self-control networks.

By learning to accept discomfort (e.g., the boredom of a tedious task or the anxiety of a challenging one) without immediately running away from it, people can stay engaged in tasks for longer. Some research suggests that mindfulness practice can indeed change the brain's responses to stress and improve concentration, offering a biological complement to behavioral change.

Additionally, emotion-focused therapies may help procrastinators address underlying fears (such as fear of failure or criticism) so that these fears no longer unconsciously drive avoidance.

Time management and organizational skills: On a practical level, time management training can help prevent procrastination.

This includes learning to prioritize tasks, set milestones, and use scheduling tools. For someone who is prone to procrastination, externalizing their plan (e.g., writing down a start time for a task, using reminder apps) can compensate for deficiencies in internal self-regulation. Even simple strategies like the Pomodoro Technique (working for a focused 25-minute interval followed by a short break) can trick the brain into perceiving a daunting task as manageable.

These strategies work by reducing feelings of overload and increasing the immediacy of rewards (each completed Pomodoro interval provides a sense of accomplishment and a break as a reward). While time management alone may not address deeper emotional avoidance, it is a useful tool in an overall anti-procrastination toolbox.

Motivational techniques: Procrastinators often benefit from increased motivation for tasks.

Techniques derived from self-determination theory and motivational interviewing can help people connect tasks to their personal values or long-term goals, thereby increasing the perceived value of the task. Another evidence-based strategy is to formulate implementation intentions—specific “if-then” plans that predetermine how to act in a given context. For example, “If it is 7:00 PM, then I will spend 30 minutes reviewing my exam notes.”

Such plans reduce mental friction at the moment of initiating action, effectively making goal-directed behavior automatic. Meta-analyses have found that the technique of “formulating implementation intentions” can significantly improve goal completion and reduce procrastination by creating situational cues for action.

Also, committing to small beginnings (e.g., telling yourself to work for just 5 minutes) often overcomes initial resistance; once a person is engaged, they often continue for much longer. This takes advantage of the psychological phenomenon that starting a task is the biggest hurdle—known as the Zeigarnik effect, an unfinished task creates cognitive stress that often pushes us to continue once we’ve started.

On the biological side, while we can’t change our genes, there are intriguing possibilities for leveraging neuroscience in interventions. For example, since procrastination has been linked to amygdala overactivity and stress response, stress reduction techniques (exercise, meditation, adequate sleep) could have indirect neurological benefits.

Regular aerobic exercise is known to improve executive function and can increase dopamine and serotonin levels, which may help combat the low energy or low motivation that fuels procrastination. In extreme cases, where procrastination is associated with clinical conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], medication may be considered.

Stimulant medications that increase dopamine availability have been shown to improve task initiation and reduce impulsive inhibition in the ADHD population, although they are not a stand-alone treatment for procrastination and their use should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Innovative approaches such as neurofeedback or brain stimulation are also being explored: Since research has identified specific neural circuits (e.g., frontostriatal networks) that underlie procrastination, interventions such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) could theoretically strengthen prefrontal control networks—but this is still experimental. Researchers have even suggested that “specific training or brain stimulation” targeting these neural pathways might improve action control in the future.

Ultimately, the most effective way to reduce procrastination is most likely to combine strategies. For example, a person might use CBT techniques to address irrational thoughts, use time management tools to organize tasks, and practice stress management to reduce emotional triggers for avoidance. Such a multifaceted approach recognizes that procrastination can stem from habits, emotions, and neurobiology all at once.

Overcoming procrastination requires not just willpower in the moment, but an ongoing effort to reorient one’s habits and responses—in effect, retraining both the brain and the psychological system toward more adaptive patterns of behavior.

Conclusion

Procrastination is a complex behavior with both biological and psychological underpinnings. Biologically, some people are predisposed to procrastination due to genetic factors and neural circuits that favor short-term reward or avoidance of heightened threat.

Psychologically, procrastination is reinforced by cognitive distortions, emotional coping patterns, and personality traits that undermine self-regulation. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive; instead, they interact to create the all-too-familiar scenario of wanting to do a task but irrationally putting it off.

Understanding these mechanisms provides a more compassionate and nuanced view of procrastination – it is not simply about laziness or poor time management, but about a conflict between our current urges and future goals, mediated by brain chemistry circuits and past learning.

Combining perspectives also illuminates many paths to reducing the phenomenon. Interventions ranging from cognitive-behavioral strategies to mindfulness meditation can help recalibrate the psychological drivers of procrastination, while healthy lifestyle changes and perhaps targeted therapies can support the biological aspect of self-control.

For example, learning to tolerate discomfort through mindfulness directly counteracts the limbic urge to escape, and setting external aids (deadlines, reminders, accountability partners) supports the prefrontal executive system in guiding behavior. Over time, successful procrastination reduction is self-reinforcing: As people experience the rewards of timely action—reduced stress, a sense of accomplishment, improved performance—their attitudes and neural responses can change, making it easier to initiate tasks in the future.

In summary, procrastination can be seen as a case of “internal conflict” in which our evolutionary wiring and learned habits sometimes work against our intentions. By identifying the biological and psychological mechanisms at work, researchers and clinicians can develop more effective strategies to help people break the cycle of procrastination.

And on a personal level, understanding why we procrastinate is the first step toward overcoming it—transforming the struggle between immediate gratification and long-term benefit into a more harmonious internal alliance in service of our goals.

References

Sirois, F. M., Stride, C. B., & Pychyl, T. A. (2023). Procrastination and health: A longitudinal test of the roles of stress and health behaviours. British Journal of Health Psychology.

Le Bouc, R., & Pessiglione, M. (2022). A neuro-computational account of procrastination behavior. Nature Communications, 13, Article 5639.

Chen, G., & Lyu, C. (2024). The relationship between smartphone addiction and procrastination among students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 224, Article 112652.

Rozental, A., & Carlbring, P. (2014). Understanding and treating procrastination: A review of a common self-regulatory failure. Psychology, 5(13), 1488-1502.

Kljajic, K., Schellenberg, B. J., & Gaudreau, P. (2022). Why do students procrastinate more in some courses than in others and what happens next? Expanding the multilevel perspective on procrastination. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 786249.

Zhou, M., Lam, K. K. L., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Metacognition and academic procrastination: A meta-analytical examination. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 40(2), 334-368.

Grunschel, C., Patrzek, J., and Fries, S. (2013). Exploring reasons and consequences of academic procrastination: an interview study. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28, 841-861.

Procrastination in the Model We Develop for the "Self"

In our model, the self includes the components of the human mental apparatus. The model first assumes the existence of the "primary self," which is in fact the basic biological nucleus consisting of a number of innate structures and subject to development throughout life. This self includes the instinctive emotional and cognitive parts of the person.

The primary self uses the reservoirs and mechanisms of emotion, memory, and cognitive abilities and contains the initial nuclei for the future development of other mental structures.

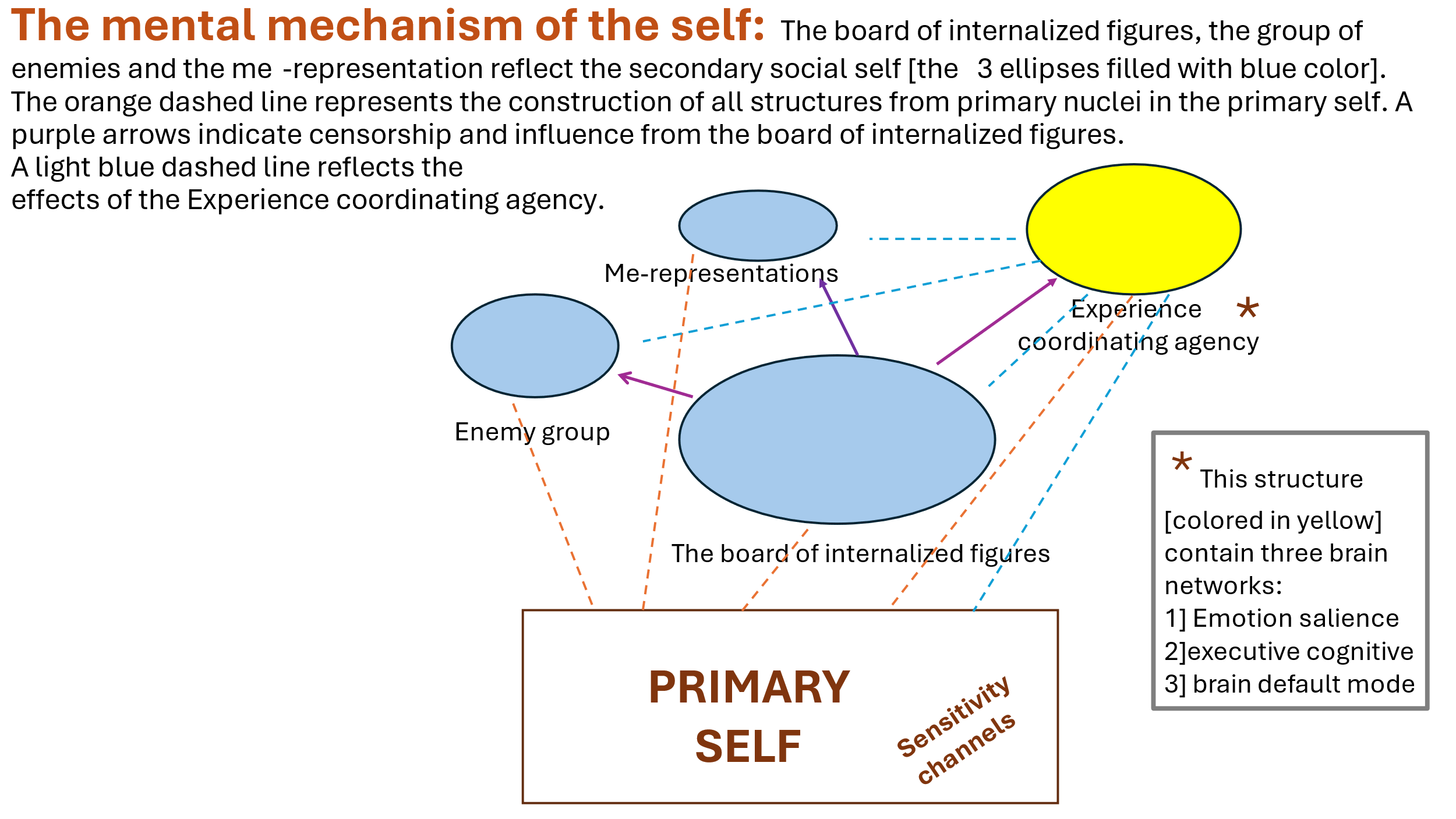

An illustration of our proposed new self model.

Let us first consider the primary self (predestined biological core): The primary self consists of innate biological structures and instincts that form the innate basis of the parts of the personality and also includes cognitive and emotional processes.

This primary self has its own dynamics throughout a person's life and is subject to changes with age, following illness, trauma, drug use, addiction, etc. Both the instincts and basic needs in each person vary according to different periods of development and aging (and hence their influence on behavior) and may be altered by medications, trauma, illness, etc.

Within the primary self there is the potential for instrumental abilities that are innate, but they can also be promoted, or conversely, suppressed, through the influence of reference groups. The primary self also has cognitive abilities that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment in the first years of life. In addition, it includes temperament and emotional intelligence that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment in the first years of life.

Finally, it includes an energy charge that is primarily innate but can be suppressed through the influence of reference groups, as well as through various situational factors.

The primary self also includes the seven channels of personal sensitivity: Individual Sensitivity Channels (ISC) that reflect our personal response in response to stressors (both external and internal). So far, we have identified seven sensitivity channels:

1. Sensitivity to one's status and position (status channel)

2. Sensitivity to changes in norms (norms channel)

3. Sensitivity to emotional attachment to others (attachment channel)

4. Sensitivity to threat of any kind – physical, economic, etc. (threat channel)

5. Sensitivity to routine changes (routine channel)

6. Sensitivity to changes in energy levels and the ability to act derived from it (energy channel)

7. Sensitivity to proprioceptive stimuli coming from the body (proprioceptive channel).

From the primary self, a number of innate nuclear superstructures continue to develop that form the basis for the development of the baby and later the person throughout his life with the figures around him: three structures that together make up the secondary self or the social self, including:

A] The group of internaized figures that we metaphorically call a board or directorate of internalized figures,

B] The group of internalized enemies (the enemies’ group),

C] The group of internalizedd self-representations.

The internalized figures’ system consists of internalizations of influential figures in a person's life, arranged in a hierarchical order [as mentioned, we metaphorically call this group of internalizations the board or directorate of internalized characters].

These figures have an ongoing dialogue between them and sometimes even conflicts, with one or more of the internalized figures having the greatest influence on the individual's attitudes, feelings, and behavior, which we have called the "leader self" [a figure previously also called the "dictator self," see previous discussions]. The attitudes of the internal leader play a central role in making decisions about internalizing information and figures.

He decides whether to reject the internalization or, if accepted, in what form it will be internalized. In other words, in a certain sense, we assume that this influential figure is also a kind of internal censorship. It should be emphasized that these are not concrete hypotheses about the presence of internalized figures in the individual's inner world as a kind of "little people inside the brain," but rather about their representation in various areas of the brain whose nature and manner of representation still require further research.

We should also note that although we call this character the "leader self", with the exception of a certain type, his characteristics are not the same as those of a ruler in a particular country, but rather this character is dominant and influential among the "character board".

We should note that the events and characters in the external world maintain a kind of dialogue mediated by the "experience coordinating agency" [see previous conversations] with the internalized characters on the board [or with the group of internalized enemies – see below] and may affect the expression and sometimes even the hierarchy of the characters on the internalized characters’ board.

In addition, it is possible that, similar to short-term memory, parts of which are transferred to long-term memory, also with regard to the internalization of characters into the board, there is a short-term internalization, which, depending on the circumstances, importance and duration of the character's influence, will ultimately be transferred to long-term internalization in the internalized characters board.

The structure of the internalized characters’ board is as follows: This board consists of "secondary selves" that include the following types:

1) Representations of internalized figures that originate from the significant figures that the person has been exposed to during his or her life, but as mentioned, there may also be imaginary figures represented in books, films, etc. that have greatly influenced the person.

2) Internalized representations of "subculture" [subculture refers to social influences in the environment in which a person lives and are not necessarily related to a specific person].

We note that a person is usually unaware that his or her actions, feelings, and attitudes are caused by the dynamic relationships between these internalized figures.

We will add that internalized key figures in the board [usually human], usually refer to significant people in a person's life who have played key roles in shaping their attitudes, beliefs, values, and self-perception. These figures may include family members, friends, mentors, teachers, or any other influential person who has left a lasting impression on the person's psyche. Sometimes, these will also include historical, literary, and other figures who have left a significant mark on the person and have been internalized by them.

The term "internalized" implies that the influence of these key figures has been absorbed and integrated into the individual's thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors. This internalization occurs through the process of observing, interacting, and learning from these important people.

As a result, the individual may adopt certain values, perspectives, and approaches to life that reflect those of the influential figures. These internalized figures can serve as guiding forces in decision-making, moral reasoning, and emotional regulation.

We should also note that from the primary self, there evolves a structure called the "enemies’ group". Thus, in addition to the internalized characters’ board, the social self also has an "enemies’ group," or more precisely, an "internalized enemies’ group."

This is the place where the characters who significantly threaten the person are internalized, while the dominant characters in the characters’ board prevent them from entering and internalizing within the characters’ board (we have assumed the existence of this group in the past year in light of the thought of the evolutionary need of animals and humans to create such a group for their survival).

The characters in the "enemies’ group" are characters with negative emotional value and are represented more schematically in comparison to the characters in the internalized characters’ board.

We note that the transition between the internalized character board and the enemies’ group is usually not common or even rare and usually occurs following a traumatic or threatening event for a person.

In addition, from the primary self, as mentioned, a supergroup of "self-representations" develops at different life stages [for example, the representation of the self as a child, as a teenager, as an adult, etc.], including body representations. The self-representation in a certain sense is also a kind of container for the flow of information about emotional attitudes and behaviors from the dynamics in the characters’ board.

We note that each of the internalized characters in the characters’ board and the internalizations in the enemies’ group and the ego representations’ group have their own attitudes.

While the leader figure (or figures) on the internalized board exemplify the most senior and dominant roles in the hierarchy of board figures, they may censor figures who will or will not join the board if their attitudes conflict with those of the leader or leaders, and sometimes even join the enemies’ group if they pose a significant threat to the internalized leader or leaders on the board.

As mentioned, our theory behind the "Self" model divides the human mental apparatus into two broad domains: 1. the primary self (a predetermined but developable biological core): this includes, among other things, innate biological structures, instinctive emotional and cognitive processes, and seven sensitivity channels (including the "threat channel"). These channels determine how a person responds to stressors, with the threat channel being critical in assessing danger.

2. The secondary or social self: It consists of internalized figures – organized in a hierarchical board or board of internalized figures (including a dominant "inner leader"), a group of internalized enemies, and a group of self-representations. The "board of internalized figures" group usually reflects influential internalized figures from the environment, including influential virtual figures from literature and other subcultural representations, while the "internalized enemies’" group contains negative representations of those perceived as threatening.

An illustration of the model of the Self that we are developing.

We will first note that there may be different types of procrastination, for example, there may be procrastination regarding the person's own actions but not regarding an important and significant external figure for the person who has a hierarchically high internal representation in the internalized board of figures. In addition, there may also be procrastination regarding a completely new action that the person has not experienced, as opposed to procrastination regarding actions that are familiar to the person.

Procrastination and the Self Model

Procrastination can be elucidated through the lens of the primalry self model, which views human mental life as anchored in a fundamental, biologically-biased structure— the primary self. According to this model, the primary self is comprised of innate biological structures, instincts, and primary cognitive and emotional cores [that develop over the course of life] that influence behavioral tendencies such as procrastination.

At the heart of procrastination is the interplay between the innate and developed tendencies of the primary self and one’s seven individual sensitivity channels (ISCs). These sensitivity channels influence how a person perceives and responds to internal and external stressors, and significantly shape procrastination behavior.

For example, heightened sensitivity in the routine channel may cause people to avoid tasks that are perceived as disrupting their usual comfort or established routine, thereby increasing procrastination tendencies.

The energy channel, which reflects an individual's sensitivity to perceived subjective energy levels, can also have a strong influence on procrastination. When this channel is sensitive or disrupted, people may experience fluctuations in perceived energy or motivation, leading to delays in starting tasks due to insufficient perceived energy levels.

Similarly, hypersensitivity in the threat channel – associated with the amygdala and the stress response – can increase emotional aversion to performing tasks associated with any perceived threat, and encourage avoidance behaviors as a self-regulatory strategy for managing negative emotions and anxiety.

Sensitivity in the social norms channel will also make it difficult to perform tasks that contradict it and lead to their postponement.

Interestingly, sensitivity in the status channel can increase motivation or, conversely, lead to procrastination, depending on the effect of the nature of the task on the person's status.

In addition, sensitivity in the attachment channel will lead to doing and not postponing tasks related to a particular person whose attachment is very important to the individual unless the task may distance that person or damage the relationship with him.

Finally, sensitivity in the proprioceptive channel will lead to focusing on performing tasks regarding the body and its health or, conversely, postponing such tasks for fear of their consequences.

It is said here that if sensitivity in a particular channel can affect both directions [procrastination versus execution depending on the situation], then other factors such as the internalized direcctorate, the enemies’ group, self-representations, or the experience coordinating agency can apparently, alongside the nature of the situation, influence the direction of whether to induce procrastination or, conversely, to perform a given task without procrastination.

Beyond the sensitivity channels of the primary self, procrastination is shaped by dynamic interactions with the secondary or social self. The board of internalized figures, including the influential "leader self," and subcultural representations profoundly influence procrastination patterns.

If the internal leader or the internalized representation of the subculture on the board embodies perfectionistic standards or overly critical attitudes, the individual may exhibit perfectionistic procrastination, delaying the initiation of tasks due to fear of failure or negative judgment.

Alternatively, a dominant internal leader or subculture that promotes adaptability, resilience, and realistic self-esteem may moderate procrastination by fostering task-oriented attitudes and effective emotional regulation.

The presence and influence of the internalized enemies’ group also plays a significant role. Internalized enemies— figures associated with criticism, failure, or disapproval, or threats to survival—can exacerbate procrastination by intensifying and increasing anxiety surrounding task engagement. Such internal enemies may foster avoidance and procrastination behaviors by increasing the perceived emotional risks associated with tasks, thereby provoking procrastination as an escape mechanism from potential internal conflict.

Furthermore, internalized self-representations influence procrastination through their influence on self-efficacy and decision-making confidence. Relatively negative self-representations, often rooted in past failures or critical appraisals, may reduce an individual's confidence in successfully completing tasks, fostering decision-making procrastination and avoidance behavior.

In contrast, positive self-representations, reflecting ability and resilience, strengthen self-efficacy and enhance rapid engagement in tasks.

Interventions targeting procrastination within this model therefore involve strengthening positive interactions between these internalized constructs and sensitivity channels.

Approaches may include cognitive-behavioral strategies aimed at restructuring internalized self-representations, mindfulness practices to regulate sensitivity channel reactivity, and psychoeducation to reinforce the positive influence of adaptive internalized leaders.

By addressing procrastination at both the biological (primary self) and psychological (secondary self) levels, more comprehensive and lasting behavioral change can be achieved.

In the model [see diagram], the "experience coordinating agency" consists of three brain networks. The "emotional salience network" activates the emotional-executive brain network, or alternatively the default network, according to stimuli from the external and internal environments, when in a normal state there is relatively adequate regulation and balance between the activity of the latter two networks.

As mentioned, procrastination is a complex behavior that involves voluntarily delaying tasks despite awareness of potential negative consequences.

Neuroscientifically, procrastination can be linked to interactions between the brain's executive emotional network and the default mode network (DMN).

The executive emotional brain network, which primarily involves the prefrontal cortex, particularly the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), is responsible for planning, decision-making, impulse control, and emotional regulation. Effective engagement of this network allows people to set priorities, maintain attention to long-term goals, and regulate emotional responses that might otherwise interfere with task performance.

In contrast, the default mode network, which includes areas such as the medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate gyrus, and lateral parietal cortex, is primarily activated during periods of rest, daydreaming, self-reflection, or mind-wandering. Overactivity or sustained activation of the DMN has been linked to difficulty focusing attention on specific external tasks, increased introspection, and vulnerability to distraction.

Procrastination occurs when there is a dysfunctional balance between these two brain networks. Specifically, people who procrastinate often show increased activation and dominance of the DMN when faced with daunting, stressful, or difficult tasks. This overactivation leads to increased self-thinking, emotional discomfort, rumination, and anticipation of negative feelings or failure associated with completing tasks.

At the same time, reduced activity or poor connectivity within the executive emotional brain network undermines its ability to suppress irrelevant internal distractions and effectively shift focus toward task-oriented behaviors.

The interaction between these networks suggests that procrastination may not simply reflect poor time management or laziness, but a neurobiological predisposition to cognitive and emotional dysregulation.

Interventions aimed at improving the functionality and connectivity of the executive emotional network (e.g., cognitive-behavioral strategies, mindfulness training, or neurofeedback) and reducing excessive DMN activation may prove effective in reducing chronic procrastination.

Finally, we note that as mentioned, the emotional salience network directs attention either to the default network or alternatively to the executive emotional brain network, and disruption of it will contribute to an imbalance between the executive emotional brain network and the default network. This can encourage procrastination.

RGFT as a treatment for procrastination

We have previously devoted a long discussion on this blog to this Reference Group Focused Therapy (RGFT). If a significant figure in the person's past who is high on the hierarchy of internalized figures demonstrates a deferential or perfectionistic or highly critical pattern towards the person, it can be brought to the forefront in therapy and brought to the person's awareness, allowing them to choose attitudes and behaviors that are different from that of these internalized figures.

The therapist figure, which becomes increasingly internalized during therapy, can also soften the influence of the dominant figure in the internalized directorate and instill adaptive attitudes and patterns that regulate procrastination. This method can also be used to moderate relevant sensitivity channels, the relevant figure or figures in the enemies’ group, and the relevant self-representations regarding procrastination.

Case Treatment

Here is an example of RGFT intervention in a patient suffering from chronic procrastination:

R., A single male, 37 years old came with a problem of underachieving his goals throughout his entire life. He’s been in different treatments beforehand, including dynamic therapy, CBT, and NLP. He reported missing on a daily basis various activities like sports, hobby, shopping, and dating. He expressed a feeling of profound dissatisfaction with the way he handles his life and of himself in general.

In the RGFT-specific interview that explores the influence of the significant others on a person’s life he claimed his father to be the most significant person with the impact on him to be the greatest.

As the patient changed his seat for the “hot chair” acting as his father’s figure, he expressed (as his father’s figure) rather closed and inadaptive attitudes towards the others, underlined with mistrust and pessimism.

The father figure’s attitude towards the patient himself exposed itself as of contempt, low respect, and having very low expectations of a patient.

Interestingly, the patient’s identification with the father’s figure appeared so profound that initially almost all of his attitudes towards the others and himself looked like a carbon copy of the father figure’s attitudes.

The exploration of the patient’s sensitivity channels uncovered the channels of threat and routine to be the most sensitive.

The treatment addressed various aspects of the patient’s mental life but in regard to procrastination the father’s figure seemed to be the most prominent one.

As the attitudes of the father's figure were unveiled and worked through multiple therapeutic sessions, the patient started a process of disidentification from these attitudes making new a more adaptive choices.

Here is important to mention the role of the therapist in patient identification with the more adaptive and positive attitudes, including the attitudes towards the patient himself that contributed greatly to improvement of the patient’s self esteem.

During the working through with the father’s figure the patient developed a more realistic and less threatening father’s image that enabled him to engage much less the threat sensitivity channel and feel more freedom in making choices.

The patient’s sensitive routine channel was exploited to transform the new attitudes to a habit that made them much more natural and easy going.

As the treatment progressed, a patient widened the scope of his decisions, improved his self-esteem and his subjective life experience.

That’s for now,

Yours,

Dr. Igor Salganik and Prof. Joseph Levine

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Leave a comment