By Prof. Levine & Dr. Salganik

Hello to our readers,

Dissociative Identity Disorder, which was previously known as "Multiple Personality Disorder", is one of the most controversial topics in psychiatry and psychology. In recent years, there has been an increase in awareness of complex dissociation situations, along with an in-depth discussion of the validity of the disorder, its prevalence and how to treat it.

In this article we will examine dissociative identity disorder through a theoretical model for the "Self" which consists of three main components: (1) the "primary self" (2) the "directorate of internalized characters", and (3) the "internalized enemies’ group ".

We will also discuss therapeutic options derived from the model, referring to the individual sensitivity channels, to the influence of positive (mostly within the “directorate of characters”) and negative internalized figures (enemies) on the mental structure, and to the role of the inner leader in the board of internalized figures in the rehabilitation process.

AI-assisted illustration of the dissociative identity disorder

Dissociative identity disorder is defined as a mental condition in which two or more identities exist in the same person, where each identity is characterized by a different self-concept, behavior style, and even different memories (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). In many cases, there are significant gaps in the autobiographical memory, feelings of disconnection (derealization/depersonalization) and loss of time (Putnam, 1989).

Various studies indicate that dissociative identity disorder often develops as a response to complex or persistent trauma in childhood, such as physical, emotional or sexual abuse.

There are researchers and clinicians who question the reported prevalence rate of dissociative identity disorder and claim that many cases may be mistakenly labeled as a result of incorrect use of hypnotic techniques or overidentification. On the other hand, there is clinical and empirical evidence that quite a few patients with dissociative identity disorder are not properly diagnosed.

Read more »

By Prof. Levine & Dr. Salganik

Greetings to our readers,

Our model of mental life first assumes the existence of the "primary self", which is in fact the basic biological nucleus consisting of a number of innate structures and subject to increasing development during life, this self includes the instinctive emotional and cognitive parts of the person.

The primary self uses the reservoirs and mechanisms of emotion, memory and cognitive abilities and it contains primary nuclei for the future development of other mental structures.

Let's first refer to the primary self (biological predestined core): the primary self consists of innate biological structures and instincts that form the innate basis of the parts of the personality and it also included the cognitive processes and the emotional processes.

This primary self has its own dynamics during a person's life and is subject to changes with age, following illnesses, traumas, drug consumption, addiction, etc.

Both the instincts and the basic needs in each and every person change according to different periods of development and aging – (hence their effect on behavior) and may change through drugs, trauma, diseases and more.

Within the primary self is the potential for instrumental abilities that are innate, but they can also be promoted, or on the contrary, suppressed through the influence of the reference groups.

The primary self also has cognitive abilities that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment during the first years of life.

In addition, it includes the temperament and emotional intelligence that are partly innate and partly dependent on interactions with the environment in the first years of life.

And finally, it includes an energy charge that is mostly innate but can be suppressed through the influence of the reference groups, as well as through various situational factors.

he primary self also includes the seven personal sensitivity channels: Individual Sensitivity Channels (ISC) which reflect our individual reactivity in response to stressors (both external and internal). So far we have identified seven channels of sensitivity:

1. Sensitivity regarding a person's status and position (the status channel).

2. Sensitivity to changes in norms (the norms channel).

3. Sensitivity in relation to emotional attachment to others (the attachment channel).

4. Sensitivity to threat (the threat channel).

5. Sensitivity to routine changes (the routine channel).

6. Sensitivity to a drop in the energy level and the ability to act derived from it (the energy channel).

7. Sensitivity to a variety of sensory proprioceptive aspects arising from the body (the proprioceptive channel).

The less sensitive the person is in these channels, the healthier he is mentally. Great sensitivity in one or more channels may demonstrate mental pathology.

Read more »

By Prof. Levine & Dr. Salganik

Greetings to our readers,

The philosophical idea of substitution in the complex fabric of human thought, the concept of "substitute" emerges as both a practical and metaphysical entity. At its core, a substitute is what stands in the place of the other, a character entity or idea that fulfills, replaces or imitates the function of the original. However, to reduce the substitute to a mere placeholder is to ignore its profound implications in ontology, ethics, aesthetics, and epistemology.

Below we will explore the dimensions of the substitute, trace his philosophical genealogy and examine his resonance in contemporary thought.

The ontology of exchange

The substitute works in a dual mode: as a reflection and a deflection. In its reflective capacity, it reflects the essence of the source, striving to imitate its role or presence. However, in its deviation it symbolizes absence – a reminder of what is lost, incomplete or unattainable.

Heidegger's concept of "being" and "being-there" offers fertile ground for examining this duality. Substitution may be perceived as an attempt to restore or approximate an ontological presence, but at the same time it emphasizes the impossibility of complete replication.

For example, a portrait of a loved one. The portrait replaces his physical presence, evoking his essence but it also conspicuously marks his absence.

This duality invites reflection on the nature of reality and representation – an ancient discourse such as Plato's "allegory of the cave", in which the shadows serve as a substitute for the real, and confuse the boundaries between appearance and truth.

The ethics of substitute

Ethical considerations of substitute often revolve around the authenticity of the substitute and its consequences. Substituting one action, decision or entity for another is intrinsically value-laden, and carries implications about trust, responsibility and justice.

Emmanuel Levinas, in his reflections on alternatives and responsibility, touches on substitute through the ethical requirement to prioritize the other. Here, the substitute of the self with the other is not just a substitute but a deep ethical call – to stand by the other in his suffering or vulnerability.

However, ethical dilemmas arise when the exchange violates trust or diminishes the intrinsic value of the source. Replacing real relationships with business relationships, or replacing human work with automated processes, for example, raises questions about respect, autonomy and alienation.

These considerations invite us to examine the moral weight of alternative actions, and to demand a balance between necessity and irreplaceable respect.

Read more »

By Prof. Levine & Dr. Salganik

Greetings to our readers,

The human ability to perceive is not a passive reception of stimuli nor is it purely "mental theater". This concept stems from complex interrelationships between the senses and the internal models of the brain. In order to survive and thrive, we must accurately analyze what arises externally from what is created in our soul internally. This distinction underlies everything from threat detection to social interaction.

However, delusions, hallucinations, and confusion can occur when the neural processes that maintain this boundary go awry.

Read more »

By Prof. Levine & Dr. Salganik

Greetings to our readers,

Transitional objects, a term first coined by the British pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, refer to physical objects used by children to ease the transition between dependence and independence, usually during the developmental stages of early childhood.

The following is a comprehensive overview of the definition, use, and theoretical implications of transitional objects as obtained by various researchers.

In addition, we will hypothesize about the neurobiological foundations of the phenomenon, and examine the areas of the brain involved in attachment and use of transitional objects. Through the synthesis of psychoanalytic theory, developmental psychology and neuroscience, we will try to contribute to a holistic understanding of transitional objects.

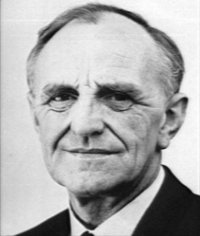

Donald Winnicott [197-1896]

Transitional objects play a significant role in child development, especially in facilitating the transition from initial dependence on primary caregivers to increased autonomy. The term "transitional object" was introduced by Donald Winnicott in 1953 and refers to an item, often a blanket or stuffed animal doll, that a child uses for reassurance and comfort when separated from their primary caregiver.

These objects serve as mediators between the child's inner world and external reality, and provide emotional regulation during key developmental transitions.

While Winnicott's conceptualization laid the foundations, later researchers built on and expanded the concept, exploring its psychological, developmental, and neurobiological dimensions.

Definition and use of transitional objects:

According to Winnicott, transitional objects are "first not me" objects that serve as a bridge between the infant's self and the world outside the mother.

They are used to help the child manage separation anxiety from their caregivers while providing comfort. Winnicott postulated that these objects embody a developmental transitional stage where the child's inner world of fantasy and outer reality begin to merge, allowing the child to explore the world independently.

Various scholars have expanded on Winnicott's work, offering different interpretations of the role and meaning of transitional objects. Bowlby's attachment theory, for example, sees transitional objects as representations of a secure base, providing emotional stability in times of distress.

Other developmental psychologists have emphasized the role of these objects in promoting emotional regulation and fostering a sense of security and continuity in the absence of a caregiver.

A teddy bear as a transitional object

Read more »

By Prof. Levine & Dr. Salganik

Dependent personality disorder is a common psychological condition characterized by an excessive need to depend and lean on others leading to submissive and clingy behavior.

Dependent personality disorder is defined by the DSM-5 as a personality disorder from the C disorder cluster characterized by an extensive and excessive need to depend on another manifested in early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts.

DSM-5 criteria:

According to the DSM-5, dependent personality disorder is diagnosed based on the presence of a pervasive and excessive need for dependence leading to submissive and clingy behaviors and fears of separation, as characterized by at least five of the following:

1. Difficulty making daily decisions without excessive advice and reassurance from others.

2. Needing others to take responsibility for most of the main areas of their lives.

3. Difficulty expressing disagreement with others because of fear of losing their support or approval.

4. Difficulty initiating projects or doing things independently due to a lack of confidence in self-judgment or self-abilities.

5. The person makes excessive efforts to receive nurturing, approval and support from others, to the point of volunteering to do things that are not pleasant to him.

6. The person feels uncomfortable or helpless when alone because of exaggerated fears of not being able to act on their own.

7. The person urgently seeks another relationship as a source of affirming nurturing and support when an existing close relationship ends.

8. The person is unrealistically preoccupied with fears that will make them worry about themselves.

Etiology

The etiology of dependent personality disorder is multifactorial, involving genetic, environmental and psychological factors. Early childhood experiences, such as overprotective parenting or conversely neglect, may cause people to develop dependent behaviors. Cognitive theories offer maladaptive schemas about self-worth and interpersonal relationships as contributing factors.

Genetics

While specific genetic markers for dependent personality disorder have not been adequately identified, family studies suggest the existence of a hereditary component. Twin studies suggest that personality traits associated with addiction, such as neuroticism and agreeableness, may have genetic underpinnings. Genetic research continues to identify specific sites and their role in dependent personality disorder in the genome.

Epidemiology

Dependent personality disorder is relatively rare, with an estimated prevalence of 0.49% to 1.5% in the general population. It is diagnosed more often in women, although this may reflect gender biases in diagnosis. Cross-cultural studies indicate variation in prevalence, perhaps influenced by social norms regarding dependence and independence.

Clinical manifestations

People with dependent personality disorder exhibit:

• Difficulty making daily decisions without excessive advice from others and reassurance.

• Tendency to allow others to take responsibility for key areas of their lives.

• Fear of abandonment and separation Urgent search for new relationships when a close relationship ends.

• Difficulty expressing disagreement from the other for fear of losing support.

• Inability to initiate projects or do things independently due to lack of confidence in personal ability.

• Tendency to exert too much effort to receive nurturing and support, even volunteering for unpleasant tasks.

Read more »

By Prof. Levine & Dr. Salganik

Greetings to our readers,

Psychological sensitivity refers to a person's heightened ability to perceive, experience, or respond to internal or external stimuli, especially those involving emotions, relationships, or social cues. This is a concept that can vary greatly between people and is influenced by personality, education, cultural factors and even biological predispositions.

Below are some dimensions of psychological sensitivity: [when we note that some of them demonstrate partial overlap].

Emotional sensitivity [sensitivity regarding emotional expression to an issue]: the ability to feel deep and intense emotions. It is possible to include in this also the ability to have a strong awareness of the emotional states of the person and others. This sensitivity is often associated with traits such as empathy and emotional intelligence.

Cognitive sensitivity: [see expansion below]. Increased awareness of nuances in information, such as language, tone or context, this includes sensitivity to criticism, feedback or ambiguous situations. This may correlate with reflective thinking or a tendency to overanalyze.

Interpersonal sensitivity: acute perception of social cues and non-verbal communication, such as body language or tone of voice. Often associated with a strong desire to maintain harmony and prevent conflict. can make people adept at navigating complex social dynamics, but can lead to vulnerability in challenging interactions.

Physiological sensitivity: the interrelationship between psychological states and physical sensations, such as a physical sensation affected by mental stress. This may include heightened sensory processing, such as being easily overwhelmed by bright lights, loud noises, or chaotic environments.

Cultural and contextual sensitivity: Awareness of how cultural or social norms shape interactions and emotional responses. Sensitivity to cultural differences or social injustices.

Illustration about increased sensitivity with the help of AI

Read more »

By Prof. Levine & Dr. Salganik

Greetings to our readers,

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) is a common but often misunderstood condition that significantly affects people's functioning in various areas, including personal, social and occupational life.

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder is a chronic and pervasive personality disorder characterized by an excessive preoccupation with order, perfectionism, and control. Unlike obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), obsessive-compulsive personality disorder does not involve intrusive and compulsive obsessions but rather a common pattern of inflexibility and rigidity in cognition and behavior. Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder affects over 2% of the general population and is associated with significant impairment.

Read more »

By Prof. Levine & Dr. Salganik

Hello to our readers,

The American diagnostic system DSM-5-TR divides personality disorders into cluster A, cluster B and cluster C. Each cluster encompasses a distinct group of personality disorders with common characteristics regarding symptoms, behaviors and basic psychological patterns.

Cluster A refers to personality disorders with odd or eccentric characteristics. These include paranoid personality disorder, schizoid personality disorder, and schizotypal personality disorder. Individuals within this cluster often exhibit social withdrawal, strange or paranoid beliefs, and difficulty forming close relationships.

Cluster B includes personality disorders with dramatic, emotional, or unstable behaviors. This cluster includes antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, histrionic personality disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder. Individuals within this cluster often exhibit impulsive actions, emotional instability, and challenges maintaining stable relationships.

Cluster C includes personality disorders with anxious and apprehensive characteristics. And these fears include avoidant personality disorder, dependent personality disorder and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. People within this cluster tend to experience significant anxiety, fear of abandonment, or an excessive need for control or perfectionism.

Avoidant personality disorder (avoidant personality disorder) included in cluster C is characterized by a persistent pattern of social anxiety, heightened sensitivity to rejection, and pervasive feelings of inadequacy, along with an ingrained longing for meaningful connections with others.

AI-assisted illustration of an Avoidant Personality Disorder

Read more »

By Prof. Levine & Dr. Salganik

Greetings to our readers,

Obsessive-compulsive disorder in an intimate relationship (Relationship Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder or ROCD) is a subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) characterized by intrusive thoughts and compulsive behaviors centered on intimate relationships. We note that there is still no complete consensus as to whether such a type of OCD disorder exists or whether it can be included under the umbrella of the accepted diagnostic definition of OCD.

It is a chronic mental condition characterized as mentioned by intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors (compulsions) aimed at reducing anxiety (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013).

While traditional OCD symptoms often focus on contamination, symmetry, or harm, a subset of people experience obsessions and compulsions related to their romantic relationships, known as relationship obsessive-compulsive disorder (ROCD).

ROCD has received increasing attention in clinical research due to its significant impact on people's well-being and relationship satisfaction.

Definition and conceptualization of OCD in interpersonal relationships.

ROCD is characterized by persistent doubts and preoccupations about the quality of the relationship, the suitability of the partner, or feelings for the partner. These obsessions often lead to compulsive behaviors such as reassurance-seeking, testing, or mental rituals aimed at reducing uncertainty.

Two main themes are common in ROCD:

Obsessions focused on interpersonal relationships: doubts about the "righteousness" of relationships, compatibility or the presence of true love.

Partner-focused obsessions: Preoccupation with perceived flaws in the partner's appearance, personality, or other qualities.

Some cite a third type of ROCD focused on retroactive jealousy to previous partners of the intimate partner or this may be classified as a subtype of the partner-focused obsessions.

Prevalence and epidemiology

While exact prevalence rates of ROCD are not well established, studies show that relationship-related obsessions are relatively common among people with OCD. ROCD symptoms can appear at different stages of the relationship with the partner and are not limited to a specific demographic.

Read more »

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.

Prof. Joseph Levine, M.D. is an emeritus associate professor in the Division of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University in Israel. Prof. Levine is a certified psychiatrist with clinical experience in controlled trials of adult psychiatric disorders and in psychotherapy. He was awarded a NRSAD independent investigator grant for the study of Creatine Monohydrate in psychiatric disorders -- mainly Schizophrenia. He resides and treats patients in Tel Aviv and all of central Israel.